By Barbara Haber

The enormous popularity of British television's "Downton Abbey" is a great boon to PBS, which is airing it in the United States, and I suspect its huge success may have come as a surprise. Though PBS anticipated Emmy awards last year for costumes and for Maggie Smith's performance in the juicy role of an aristocratic dowager, the show also walked away with awards for best writing, directing, cinematography and for the best miniseries or movie. Audiences love the story lines that zip between the behavior and happenings of upstairs gentry and the gossip and activities of below-stairs servants who make possible the gracious style of living enjoyed upstairs.

One should never underestimate the American fascination with the British class system. We love to learn the details about the contrasting problems facing each class, and how they deal with them. The upper class has time on its hands and must figure out which fashionable outfit to wear for dinner, while those below stairs in their aprons and caps must slave away to get elegant meals on the table. What both classes share, however, is a knack for getting into interesting sexual entanglements. So, in the end, "Downton Abbey" turns out to be a soap opera with great clothes. As always, food serves as a reliable way to distinguish the classes not only by what is eaten but where and with whom it is eaten, and in the case of "Downton Abbey," who cooks the food, who serves it and who gets to sit comfortably while being served.

Related: Scotch Eggs recipe, adapted from "Margaret Powell's Cookery Book"

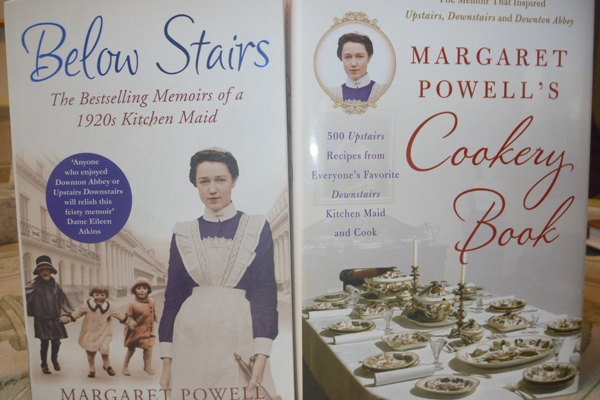

This series has inspired a small industry of books, some offering behind-the-scenes photographs and chat about the actors and sets; others dipping into social history to give the reader a bit of context. Even cookbooks with Edwardian recipes written by contemporary writers are coming along. But, for me, the best book that relates to the show was written many years ago by Margaret Powell, an English girl from a poor family who worked her way up from kitchen maid to cook in several great houses. Her memoir is said to have inspired Julian Fellowes, "Downton Abbey's" writer.

Born in 1907, Powell went into service when she was 15, landing in several upper-class homes first in the kitchen doing the dirtiest jobs in the household and eventually as a respected cook. Her memoir, "Below Stairs" gives us an authentic picture of what life was like for servants before World War I and after, the years portrayed in "Downton Abbey."

Related: Syllabub is old-school spiked cream, British style

Happily, Powell also wrote a cookbook that informs us of the dishes served to the well-born. We do not find here English foods with such amusing and, sometimes off-color names as Bubble and Squeak, Toad-in-the-hole or Spotted Dick. Instead, we get dishes clearly influenced by French cuisine, an array of proper recipes for stocks, and directions for such classic pastries as choux and pâte feuilletée. This is not surprising since the fame of French cooking was spread by the presence of French-born chefs in many of the British great houses and gentlemen's clubs. This prestigious fare then trickled down to the smaller private homes of gentry who cared about status and saw to it that guests were served impressive French dishes. But we know Powell's cookery book was written by an Englishwoman when we come across recipes for such British classics as treacle tart, the pub favorite known as Scotch eggs and curried eggs, which is a dish that reflects the British rule in India.

Related: Welsh recipes for a proper tea

Learning how to cook was not easy for Powell who, in her first job as kitchen maid, faced a mean-spirited cook unwilling to teach her young assistant. Instead, Powell found herself stuck with such nasty jobs as cleaning smelly game that had been hanging for weeks, and skinning dead rabbits in one fell swoop. In another job, when Powell told her employer that she wanted to attend cooking school, she was given the time off, but had to pay for lessons herself out of her meager salary. When she did, she found herself taken in by a fraudulent Englishman pretending to be a French chef. She quit when she realized that his frequent outbursts of "oui, oui" and "mais non" were the extent of his knowledge of the French language, reflecting as well his limited knowledge of French cooking.

But Powell soldiered on, moving ahead as a cook, revealing her deepening knowledge by saying, "the less cooking you know how to do, the more competent you feel. ... The more experienced I got the more I worried. I soon realized when a dish wasn't perfection." These are revelations of a real cook that could have been uttered by Thomas Keller today.

Related: Recipe for an English pudding classic

Powell left service when she married a milk-delivery man and set up her own household, earning extra money from time to time by catering events. She later took courses and began writing books, including novels as well as her popular memoir "Below Stairs." Her later success was in contrast to the lives of most British household servants who remained poor and subservient all of their lives.

Being stuck like this intrigues Americans who have always seen themselves as living within a fluid society in which success is attainable. At the same time, we are a bit scornful of the idle classes who spend spare time shooting small birds and animals for others to clean and cook.

Season 3 of "Downton Abbey" premieres on PBS on Jan. 6

Zester Daily contributor Barbara Haber is an author, food historian and the former curator of books at Radcliffe's Schlesinger Library at Harvard University. She is a former director of the International Association of Culinary Professionals, was elected to the James Beard Foundation's "Who's Who's in Food and Beverages" and received the M.F.K. Fisher Award from Les Dames d'Escoffier.

Top photo: "Below Stairs" by Margaret Powell. Credit: Barbara Haber