On Sept. 11, 2001, New York Post photographer Bolivar Arellano was assigned to follow mayoral candidate Fernando Ferrer’s every move. Ferrer was favored to win the Democratic primary that day. No Latino had ever had a better chance of being elected mayor of New York.

Then history intervened, and the primaries were postponed until 16 days later. Michael Bloomberg would ultimately win the mayoral election.

But that morning Arellano began early in the Bronx, taking pictures of a historic candidate. Once his shots of Ferrer were taken, Arellano called to ask his editor about another assignment. His boss said he should return to the office to process his photos. In those days, photography was just beginning the technological transition to digital images.

As Arellano developed the film, his boss's voice came over the intercom, telling him to head immediately to lower Manhattan, where a plane had crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center. Arellano grabbed his camera and raced out of the newspaper’s offices on 47th Street and 6th Avenue.

While he was still in his car, his wife, Brunilda, called to tell him that the fiery crash was being broadcast live on television, to which he replied that he was on his way there. From his car, he could see a thick, black cloud of smoke coming from both towers. As he later learned, a second aircraft had struck the south tower.

Arellano spoke recently to Huffington Post Latino Voices, vividly detailing that day’s events. He said that 10 blocks beyond the blazing towers, police had already cordoned off the area and he was initially turned away. With a little cunning, he convinced police to let him pass. He was able to drive within three blocks of the towers, at which point it was impossible to advance any further as hundreds of people ran frantically from the scene.

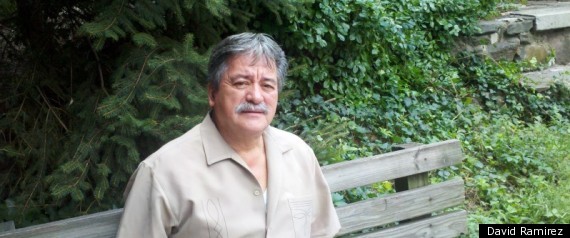

As he told the story, Arellano's eyes filled with tears and his voice broke. A week before the attacks, he had celebrated his 57th birthday. He was born on Sept. 3, 1944, in Alausi, a farming town in the Chimborazo province of Ecuador. Ten years ago, he was tireless, but today he is prematurely aged and still unnerved by the tragedy.

“As people fled, I was doing the job I’ve done all my life, taking pictures. Images I took before that day couldn’t compare with what I saw. It was very powerful. People were throwing themselves off the towers, their bodies disintegrating into nothing as they slammed into the ground,” he said, running his fingers through his graying hair.

Arellano continued his story in fragments. He recalled police officers shouting at him to leave, warning him that it was too dangerous to remain so close to the towers. He remembers the chaos: police cars, firefighters, the wailing of sirens and the screams of people pleading with those trapped in the towers not to jump.

“Of course, no one heard, and they continued to jump into the void," said Arellano. "Inside I asked God that if he had to take them, to give them wings so that they wouldn’t die that way. I don’t know.”

Arellano never thought the towers would collapse. He had taken photos of the 1993 attack, in which Islamic militants detonated a stolen Ryder truck filled with explosives in the basement garage of the north tower.

He said that he’d always had a certain recklessness. If it weren’t for that, he said, he'd never have made a career of photojournalism.

The Associated Press -- for whom he worked for many years before joining the New York Post -- sent him to the war zones. In the 1980s, he reported on the civil war in El Salvador. Later he covered the conflict in Nicaragua, during which he was abducted for three days by the Contra rebel militia. He also witnessed the misery of Guatemala's bloody civil war.

"In El Salvador I saw the military massacre more than 200 unarmed people they claimed were insurgents in two hours. As such, I saw unspeakable atrocities in Central America during those years, but in New York, to see almost 3,000 die in an hour to me was a nightmare I still can’t fully absorb,” he said, letting out a deep sigh.

Arellano agreed to meet for this interview at an East Village pizzeria. I thought we’d eat there while he shared his story. Instead, he drove us to an abandoned community park. We sat around a small table and spoke for almost two hours. He was overcome by emotion as he described the moment the first tower began descending to the ground.

“I was taking pictures of the people’s expressions as they watched the expanse of the burning buildings. Suddenly you could hear a loud explosion, dry like the sound of piercing metal, and then ‘trac, trac, trac,’” he recalled. “The tower was reducing floor by floor like a house of cards. I managed to take one picture and ran.”

His first thought was that if he died, he hoped someone would find the camera and develop the photos.

“In an instant, all the memories lived before that moment flashed before me. I was sure that this time I wouldn’t survive, and I mentally asked my mom to forgive me for all that I had made her suffer,” he said, as his eyes turned to the sky.

“Then came a roar. Everything went dark, and it was almost impossible to breathe. In the air, you could smell a strong odor of fuel and burning flesh. The blast threw me under a ladder, which is what saved my life. I was stunned, but I made sure that I had my camera and went on my own in the direction of the screams and the sirens,” he said.

The devout Roman Catholic says he grew up believing in miracles, but that some things can't be explained.

“So many times I came close to death. My Lord, thank you for saving me, but what is it you want from me?” Arellano questioned, remembering that the worst was still to come. The second tower would collapse a little later.

“A fellow photographer gave me water to drink and rinse off my face. We were covered in dust. The scene was hellish, and there were dead and wounded everywhere. Police and firefighters battled in their efforts to save lives, without knowing that many of them were headed to meet their own deaths,” Arellano said.

“I hadn’t fully composed myself when again I heard an apparent blast, and the second tower began to fall. This time we had nowhere to run because we were in an uncovered garage -- the kind with steel lifts that pile the cars one on top of the other. There were about 30 of us, some of whom were hurt.

“The only thing I remember was leaving my body and saying goodbye. I must have been knocked unconscious because I woke in the midst of it in complete darkness and silence. In fact, I thought I was dead because I was unable to move. Soon I saw small lights coming from the helmets of rescue workers who were removing debris. I wanted to scream, but my throat was parched and I had trouble seeing from the thick cloud of dust and smoke.”

Arellano was rescued. He remembers refusing to evacuate, telling rescue workers he was fine, although he was bleeding profusely from his right leg. He was taken to Bellevue Hospital, where a line of first-aid personnel attended the wounded, arriving by the hundreds. The veteran photographer’s priority was to guard his camera. Of the five rolls of film he took, only two were lost, he said with some happiness.

“I hope that, for humanity’s sake, there will never be anything again like September 11, but as the world goes, I don’t know. I can’t be sure there won’t be more misfortune,” he said.

Now, Arellano reflects on life with a greater appreciation for merely being alive. He also speaks of a newfound spirit that allows him to face life.

“My only wealth is all that I’ve lived. I live with the barest essentials. I don’t own property, and I pay rent," he said. "My greatest satisfaction has been to do good and help those in need.”

Arellano received compensation for working during 9/11; he distributed the money to the poor and donated funds to rebuild a school in his old village.

“The school was almost abandoned. Because of the terrible conditions, there were barely students. We helped to rebuild the school and donated 12 computers,” he said.

In the days after 9/11, Arellano said he changed. He couldn’t sleep from the nightmares -- and when he did, he woke in tears the following morning.

“I refused to get therapy. I was afraid that it would be recorded in my medical history. I feared losing my job,” he said. “Four years after 9/11, I couldn’t stand it anymore [and agreed to seek therapy]. I chose to continue therapy sessions because I felt worse and worse.

“The images of the tragedy would repeat constantly in my mind. I recognized what I’d experienced, and I unhinged, mourning in tears. I insisted that no one know how bad I was emotionally, and I tried to ignore reality. I’m sure, though, that I haven’t been the same since,” he said as he looked away.

Bolivar Arellano couldn’t continue working. After 30 years with the New York Post, he retired in 2004.

WATCH RELATED: