By David Basulto(click here for original article)

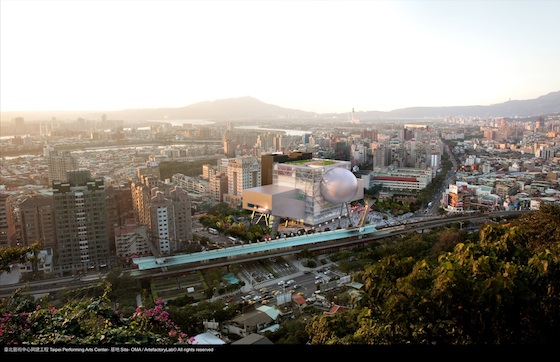

Nearly two years after OMA was announced winner of a two-stage international competition, the construction of the new Taipei Performing Arts Center has commenced. This ambitious project, led by OMA partners Rem Koolhaas and David Gianotten, generated a lot of debate among architects when it was announced back in 2009 due to its particular form. Morphed by a series of programatic operations, the form intersects three types of theater in order to accommodate a variety of performances.

TPAC Approach from north © OMA

TPAC Approach from north © OMA

The main theater, which seats 1,500, is expressed on the exterior as a large sphere while the two smaller theaters, each capable of seating 800, are represented as peripheric cubes. All the stage accommodations are brought together within the central cube, allowing for more flexibility as theaters can be used independently or combined, thus expanding the possibilities for experimental performances – an art which is very strong inTaiwan. At the same time, and in a similar way as OMA’s CCTV building in Beijing, China, a “public loop” channels circulation through the building, exposing the spaces that make the TPAC work, areas typically hidden from the public but are as revealing as the performances themselves.

In this aspect, the building is like a machine at work with its engine exposed, somehow reminding me of OMA’s Prada Transformer – a machine-like building (the anti-blob) that changed its configuration to host different types of events.

The 180 million dollar project is set to be completed in 2015.

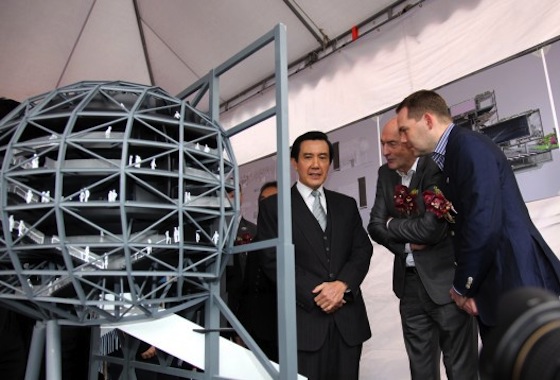

President Ma Ying-jeou with OMA partners Rem Koolhaas and David Gianotten © OMA

President Ma Ying-jeou with OMA partners Rem Koolhaas and David Gianotten © OMA

Why have the most exciting theatrical events of the past 100 years taken place outside the spaces formally designed for them? Can architecture transcend its own dirty secret, the inevitability of imposing limits on what is possible?

In recent years, the world has seen a proliferation of performance centres that, according to a mysterious consensus, consist of more or less an identical combination: a 2,000-seat auditorium, a 1,500-seat theatre, and a black box. Overtly iconic external forms disguise conservative internal workings based on 19th century practice (and symbolism: balconies as evidence of social stratification). Although the essential elements of theatre– stage, proscenium, and auditorium– are more than 3,000 years old, there is no excuse for contemporary stagnation. TPAC takes the opposite approach: experimentation in the internal workings of the theatre, producing (without being conceived as such) the external presence of an icon.

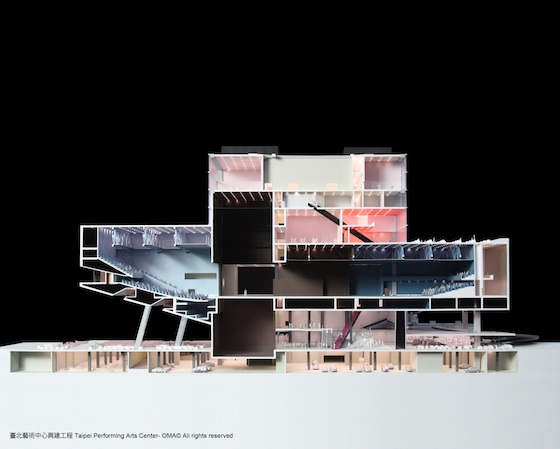

TPAC section model © OMA

TPAC section model © OMA

TPAC consists of three theatres, each of which can function autonomously. The theatres plug into a central cube, which consolidates the stages, backstages and support spaces into a single and efficient whole. This arrangement allows the stages to be modified or merged for unsuspected scenarios and uses. The design offers the advantages of specificity with the freedoms of the undefined.

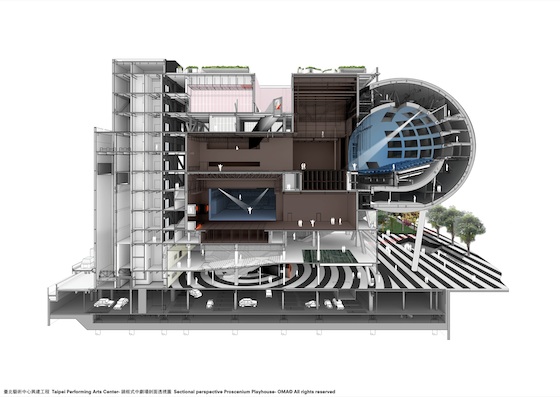

Section © OMA

Section © OMA

Performance centres typically have a front and a back side. Through its compactness, TPAC has many different “faces,” defined by the individual auditoria that protrude outward and float above this dense and vibrant part of the city. The auditoria read like mysterious, dark elements against the illuminated, animated cube that is clad in corrugated glass. The cube is lifted from the ground and the street extends into the building, gradually separating into different theatres.

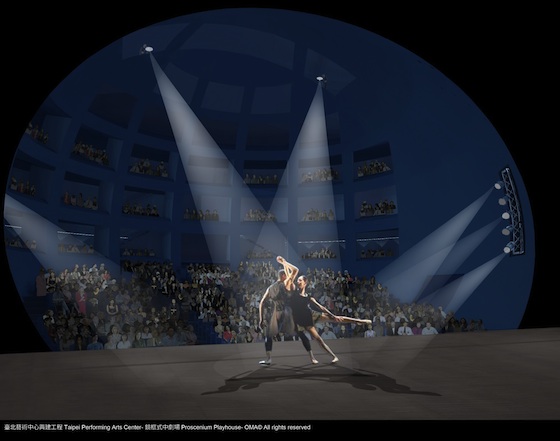

TPAC proscenium playhouse © OMA

TPAC proscenium playhouse © OMA

The Proscenium Playhouse resembles a suspended planet docking with the cube. The audience circulates between an inner and outer shell to access the auditorium. Inside the auditorium, the intersection of the inner shell and the cube forms a unique proscenium that creates any frame imaginable.

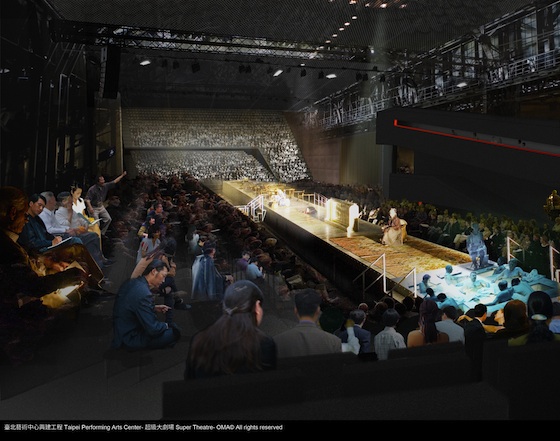

TPAC Super theatre © OMA

TPAC Super theatre © OMA

The Grand Theatre is a contemporary evolution of the large theatre spaces of the 20th century. Resisting the standard shoebox, its shape is slightly asymmetrical. The stage level, parterre, and balcony are unified into a folded plane. Opposite the Grand Theatre on the same level, the Multiform Theatre is a flexible space to accommodate the most experimental performances.

TPAC Supertheatre © OMA

TPAC Supertheatre © OMA

The Super Theatre is a massive, factory-like environment formed by coupling the Grand Theatre and Multiform Theatre. It can accommodate the previously impossible ambitions of productions like B.A. Zimmermann’s opera Die Soldaten (1958), which demands a 100-metre-long stage. Existing conventional works can be re-imagined on a monumental scale, and new, as yet unimagined forms of theatre will flourish in the Super Theatre.

TPAC public loop © OMA

TPAC public loop © OMA

The general public—even those without a theatre ticket—are also encouraged to enter TPAC. The Public Loop is trajectory through the theatre infrastructure and spaces of production, typically hidden, but equally impressive and choreographed as the “visible” performance. The Public Loop not only enables the audience to experience theatre production more fully, but also allows the theatre to engage a broader public.

Project: Taipei Performing Arts CenterStatus: Competition: 2008-2009.Construction begins: 2012.Scheduled completion: 2015Client: Department of Cultural Affairs, Taipei City Government

Budget: Estimated: 5.4 billion Taiwan Dollars (around €140 million)Program: Total 50,000m2. One 1,500-seat theatre and two 800-seat theatresHeight: 63m

Partners-in-charge: Rem Koolhaas, David GianottenAssociate-in-charge: Adam Frampton

Design team: Ibrahim Elhayawan with: Yannis Chan, Hin-Yeung Cheung, Jim Dodson, Inge Goudsmit, Alasdair Graham, Vincent Kersten, Chiaju Lin, Vivien Liu, Kai Sun Luk, Kevin Mak, Slobodan Radoman, Roberto Requejo, Saul Smeding, Elaine Tsui, Viviano Villarreal, Casey Wang, Leonie Wenz

Competition team: partners / designers: Rem Koolhaas, David Gianotten, Ole Scheeren, and senior architects: André Schmidt, Mariano Sagasta and Adam Frampton, with: Erik Amir, Josh Beck, Jean- Baptiste Bruderer, David Brown, Andrew Bryant, Steven Chen, Dan Cheong, Ryan Choe, Antoine Decourt, Mitesh Dixit, Pingchuan Fu, Alexander Giarlis, Richard Hollington, Shabnam Hosseini, Sean Hoo, Takuya Hosokai, Miguel Huelga, Nicola Knop, Chiaju Lin, Sandra Mayritsch, Vincent McIlduff, Alexander Menke, Ippolito Pestellini, Gabriele Pitacco, Shiyun Qian, Joseph Tang, Agustin Perez-Torres, Xinyuan Wang, Ali Yildirim, Patrizia Zobernig

COLLABORATORS

Local architect: Artech ArchitectsTheatre consultant: dUCKS scéno, CSIInterior designer: Inside OutsideLandscape designer: Inside OutsideAcoustic consultant: DHVStructural engineer: Arup Structure, EvergreenMEP engineer: Arup MEP, Heng Kai, IS LinFire engineer: Arup Fire, TFSCLighting consultant: Chroma 33Facade engineer: ABT, CDCSustainability consultant: Arup Building Physics, Segreene Geotechnical engineer: Sino GeotechTraffic consultant: EECI TrafficModel: Vincent de Rijk, RJ ModelsPhotography: Frans Parthesius, Iwan BaanAnimation: ArtefactoryIn this aspect, the building is like a machine at work with its engine exposed, somehow reminding me of OMA’s Prada Transformer – a machine-like building (the anti-blob) that changed its configuration to host different types of events.

TPAC Birdseye view © OMA

TPAC Birdseye view © OMA