This piece comes to us courtesy of The Hechinger Report.

She thought of herself as an ordinary mother of four, one who did what she could to advocate for her kids in Newark public schools.

But Carol Tagoe’s advocacy caught the eye of a New York University education reformer. And suddenly, the disarmingly friendly Trinidad native was working for the Newark Global Village School Zone, a partnership that heralded the promise of both educational and community revival in the city’s impoverished Central Ward.

Tagoe’s role was community mobilization. Over the 2011-2012 academic year, she organized dozens of “Chat and Chews” for hundreds of parents who came out to discuss how to support their children. There was even a “spring training” just for dads. Momentum built and as Tagoe helped other parents find their voices, she strengthened her own.

“Who would’ve thought that me, an average mom, could mobilize parents to come out and seek the best interests of their children as well as the community?” said Tagoe, who is married to a manufacturing company manager and describes herself as “40ish.”

Then last August, out of nowhere, Tagoe got an email from NYU saying her services would no longer be needed. The university had pulled the plug, citing a lack of responsiveness from the district. The Global Village initiative was over.

Global Village had arrived in Newark with great fanfare just three years earlier. During its short life, it extended the school day for many children at the seven schools it served, provided eyeglasses to students who needed them, distributed books to build home libraries, and connected parents with a variety of social services, from mental health care to housing assistance.

Much like the highly publicized Harlem Children’s Zone, Global Village focused on the needs of entire families. It aimed to strengthen academics and help lift children in one of Newark’s toughest neighborhoods out of poverty.

The partnership between Newark public schools and NYU would be less expensive than the one in Harlem, potentially making it a model to be replicated nationwide. During the 2008 presidential campaign, then-candidate Barack Obama said he wanted to create 20 such zones around the country. Foundations were willing to pay for it.

But as with so many prior attempts at reform, things didn’t go according to plan.

On the national scale, President Obama shifted strategy to provide immediate direct aid through an economic stimulus package rather than investing a few billion dollars a year to create anti-poverty zones that would take longer to show results.

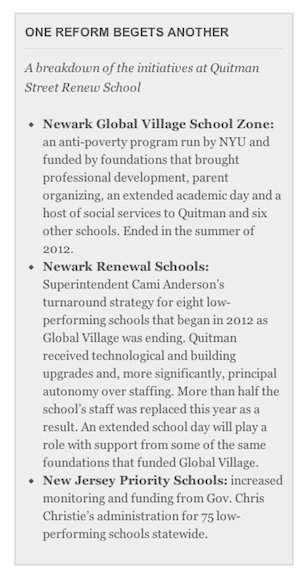

And in Newark, what had been billed as one of this downtrodden city’s most ambitious reforms collapsed just before this school year started. NYU blamed the failure on a lack of support from Newark Superintendent Cami Anderson and Mayor Cory Booker. Anderson has since begun a new reform initiative absorbing many Global Village concepts, notably the extended school day.

The life and death—and now, the reincarnation—of Global Village illustrate the complexities of turning around the nation’s lowest performing schools.

Among them is Quitman Street Renew School, with its 550 students in pre-kindergarten through eighth grade, where two of Tagoe’s children are enrolled. Quitman’s population is more than 90 percent black and low income.

Long struggling academically, Quitman has been subject to many a turnaround effort. It survived a district proposal to shut it down two years ago. It is the only Global Village elementary school with the same principal as when the initiative began in 2010.

Pedro Noguera, the NYU professor who spearheaded the initiative and is widely considered one of the nation’s leading authorities on urban school reform, says Anderson never got behind Global Village when she became Newark’s superintendent in 2011, nor did Booker. This year, Anderson closed three Global Village schools.

Now the remaining Global Village elementary schools, including Quitman, are targets of a new effort. They are among eight “renewal schools” in Newark that received building and technological upgrades last summer. Their principals were allowed almost free rein to hand-pick their own staff. They are also slated to have longer days.

Anderson’s administration said foundations will work directly with the renewal schools to fund the services they need without NYU taking a cut as middleman. And those services will be provided against a backdrop of much stronger principal and teacher accountability for academic outcomes, including the new teacher performance bonuses included in a historic contract ratified in mid-November.

“For the first time, Newark Public Schools is putting forth a comprehensive turnaround strategy,” Assistant Superintendent Peter Turnamian said. With Global Village, he said, NYU had assumed many functions of a school district—it provided strategic direction and valuable training in addition to being an intermediary for social service grants—and the district was no longer willing to outsource its responsibilities.

Low-performing schools tend to get stuck in what Noguera calls “reform churn,” where nothing stays in place long enough to take hold. Although components of Global Village continue under the renewal school initiative, services were disrupted during the transition and parents felt let down again.

“Newark’s been through so much in terms of having promises made and not fulfilled, and I think that’s the worst part of this,” Noguera said.

At the same time, schools like those in the Global Village zone are often subject to many reform efforts at once, resulting in inefficient and impractical measures that can be confusing and maddening for staff.

Quitman is now a renewal school. It is also getting state monitoring and money through yet another program, Gov. Chris Christie’s initiative for low-performing schools. As November drew to a close, Quitman’s principal was finalizing details on how he will use money from the state program combined with funding from the new teachers contract to restore the extended day for the rest of the academic year.

Beyond bureaucratic complications is the difficulty of tackling education in tandem with poverty. The philosophy behind Global Village was that poverty is inextricably linked with academic performance, a force more than schools are able to handle on their own.

“If you want to really build sustainable school reform then you have to take into account poverty, the conditions of communities, and you have to work intentionally and systemically to weave all kinds of relationships and supports,” Lauren Wells, who administered Global Village for NYU, told WNYC last spring.

It was Wells who hired Tagoe to work with the community in support of its children.

Rather than using poverty as an excuse, Wells said, “you have to consider poverty and the impacts of poverty in everything that you do to support kids’ success in the schools.”

'THE MOST AMBITIOUS REFORM'

In a July 2010 article in The New York Times about the launch of Global Village in Newark, educators and parents called it “the most ambitious reform to be tried here in decades.”

The idea was to focus intensely on the needs of students and families at the city’s Central High School and its six feeder elementary/middle schools. There would be longer school days, summer classes, health clinics and access to healthy food for the zone’s 3,500 students, in addition to extensive professional development for teachers and principals to improve academics.

“We’re going to give them every opportunity to succeed,” then-Superintendent Clifford Janey told The Times. “We’re going to get out of the way when necessary and enable leadership to grow and flourish.”

A widely distributed PowerPoint presentation outlining the plans included a slide titled “Our Challenge.”

“Our challenge,” it said, “is to ensure that bureaucratic policies [and] political agendas … do not overwhelm this potentially powerful seedling before it has an opportunity to take hold.”

Shortly after the start of the Global Village initiative, Janey had stepped down as superintendent, forced out by the governor who saw him as not strong enough on systemic reforms and too soft on teachers unions.

The American education reform world is often divided: One camp wants increased accountability for the adults in schools, and the other believes change must start at home. The first puts a premium on reforms like merit pay and charter schools and often butts heads with unions. The second, backed by unions, prioritizes social interventions.

Global Village was clearly part of Camp No. 2. The Newark Teachers Union was an enthusiastic supporter.

Noguera said it might have failed because its agenda “was not sexy enough” in a city where the mayor is a major charter school advocate and the governor is pushing stronger school accountability. Although the test scores of Global Village schools remained low, he said the schools were undergoing structural changes needed for an academic turnaround.

When Cami Anderson replaced Janey as superintendent, “she kept thinking of what we were doing as just about community engagement, which was marginalizing it because therefore it wasn’t about academics,” Noguera said. “Urban superintendents know they’re going to be judged by test scores so unless something bumps up scores, it takes a much lower priority for them.”

Neither Anderson nor Booker would respond to Noguera’s comments directly. But Anderson’s administrators say she is deeply committed to community engagement and providing social services—in the context of academic progress.

Besides the tensions between the district and NYU, several people involved in the Global Village initiative point to other issues involved in its collapse and raised questions about its sustainability.

- How much money was necessary to be effective? The Harlem Children’s Zone has an annual budget of70 million. Noguera said Global Village raised and spent about1 million in three years. The cost structure was still in flux, but was it unrealistically low?

- Should a separate nonprofit have been created to run daily operations rather than allow NYU to manage the program and take a cut of the funding?

- Could Global Village have survived in the face of dwindling enrollment due to factors including the recession and the growth of charter schools?

- Finally, was it worth investing in professional development when some staff members, tired and burnt out, didn’t appear invested in the process?

NEEDS ON ALL FRONTS

Quitman Principal Erskine Glover says his school illustrates the need for both accountability-driven and anti-poverty reforms; in his eyes, the two dueling camps are both right.

With Global Village funding in the past two years, Quitman staff received extensive professional development supervised by Wells and NYU. Glover said the training was extremely high quality, so high that he hopes to be able to dip into his own budget to keep Wells on as a consultant. But it didn’t change the fact that several teachers on his staff were not putting their all into their jobs.

“I see people working really, really hard, and not getting movement, and I know that’s a difficult place for a person to exist,” Wells said in her May interview with WNYC. (She left NYU in July and has declined to comment since.) “I also see people not working very hard at all, and that’s just beyond comprehension to me.”

This year, thanks to the power that Anderson granted Glover through the renewal school process, the principal replaced more than half the teachers on staff. He said the changes were a prerequisite for success at Quitman and vital if the school is to stand a chance of turning around.

With an energetic shift ushered in by the new teachers, Glover said, “you would’ve seen the results very quickly this year” if the professional development provided by Global Village had continued. Now he’s leading teacher training on his own.

Glover said he believed the Global Village initiative could have worked well alongside the renewal school process; with funders still willing and enthusiastic, he didn’t see why they had to be mutually exclusive.

He said he needs help meeting the many social, emotional and health challenges that his students bring to school. “It’s very hard when you have one social worker for 500 students to make sure you meet all of the needs,” he said.

Many Quitman students benefitted from Global Village’s ability to connect families with existing community resources, Glover said. One Global Village partnership did free vision testing for hundreds of Quitman students and provided eyeglasses to about 75 children found to need them. Another provided books that helped families build home libraries.

Global Village funded an extended school day for first- through fourth-graders at Quitman. From September until now, that extra time has been on hold.

Glover just figured out a way to restore and expand the extended day with the state and contract money. Starting in mid-December, all kindergartners through fifth-graders will stay until at least 4 p.m. instead of 2:55. More than 100 middle school students targeted for academic intervention will also be required to stay late, and the remaining middle school students can participate in optional clubs and tutoring.

A longer day is important to help students with academics and to keep them off the streets during the hours when young people are most likely to get into trouble.

Irene Cooper-Basch, executive officer of the Victoria Foundation, said she and other Global Village funders are still giving money but it is being redirected. They are contributing $1.2 million this year for the Newark Education Trust to divide among the renewal schools and a handful of other initiatives.

It’s too soon to say whether that will reinstate all the other services that were lost. Turnamian, the assistant superintendent, said some consolidation in positions as well as school closings were necessary to fund the renewal schools.

The district took a heavy hit financially to give principals staffing autonomy since it must pay salaries of tenured teachers who were not given placements. About 200 teachers remain in that pool, according to district officials. They are being paid even though they don’t have daily teaching assignments.

Glover had been looking forward to his students receiving access to organic food through Global Village. There was also talk of mobile dental vans to do teeth cleaning. Glover said many of his students don’t go to the dentist, and those who do often don’t have quality dental care, as evidenced by the preponderance of silver caps on their teeth. It’s a small point but it bothers him.

While Quitman has its own on-site health clinic funded by the Jewish Renaissance Medical Center, children at other Global Village schools were relying on the initiative for access to health care beyond emergency room visits.

Tagoe’s assistance with parental involvement was a key component in the Global Village initiative. Although district officials noted that each renewal school already had a full-time parent liaison, in places where parents historically have not been engaged, such efforts hardly seem duplicative to those in the trenches.

Quitman’s liaison, Stephanie Ruff, pitches in on everything from cafeteria duty to subsidized lunch applications to getting children school uniforms and shoes and then enforcing that they wear them. Late into the evenings, she and the school social worker march into housing projects and pound on doors to track down parents.

The liaisons also organize events: a year-end luncheon to promote summer reading, a back-to-school barbeque and a voter registration drive, plus district-mandated meetings about the renewal school process.

Tagoe’s meetings, aimed at parents from all seven schools in the zone and throughout the Central Ward, gave an opportunity to discuss the particulars of parenting. “I just offered something different from what a parent liaison would offer,” Tagoe said.

POWER FOR PARENTS

Andrea Peters is the mother of two girls at Quitman, in first and fifth grades. Last year she attended several Global Village “Chat and Chews” and found the sessions useful in her parenting.

“At one they had a doctor there that discussed children’s attitudes and how you can go about, instead of yelling at them, trying to do a different technique,” she recalled. “I got a lot of helpful information that I could use at home as far as reading with the kids … opening up more of a dialogue with the kids so if they have a bad day they’re not afraid to tell you.”

Peters said she appreciated the information that Tagoe regularly provided to parents about the activities of schools in the zone. “It was good to communicate with other parents from different schools and other parents in general,” she said.

Noguera said Global Village sought to right the wrongs of prior urban school reform efforts, and that meant empowering and organizing parents.

“If you go into affluent communities and you ask the educators who they’re accountable to, they always say, ‘to the parents we serve,’” he said. “That’s important because it means the parents they serve matter… If you feel as though you can disregard the parents, it’s probably going to influence the way you treat their children, too.”

When Erskine Glover thinks about the differences between Newark and the suburban district in North Brunswick where his own two children go to school, stability is the first thing that comes to mind. “There’s an element of consistency that exists in their schooling,” he said. “There’s a system and structure in place.” Turnover among superintendents, principals and academic programs is extremely rare in North Brunswick.

On the flip side, Glover sometimes worries that his son, 15, and daughter, 12, miss out on “the hardcore challenge of really having to stretch that rubber band.”

“I mean, there’s something about being a child growing up in a tough community. There’s a level of resilience that makes you who you are, and you bring it into the classroom. You’re faced with an obstacle and you fight harder,” he said. “My son’s fight is to be a starter on the soccer team… My daughter’s fight is to make sure she stays in cool with her circle of friends. It’s not the same.”

Tagoe is a Central Ward resident—she has a son and a daughter at Quitman and a son at Central, plus a daughter in college—and found that much of her job took place at the supermarket and the laundromat. The point, she said, was to “meet the community where they’re at.”

Sometimes her role was simply to lend an ear or offer a welcoming smile and hello to parents who weren’t used to getting a warm reception at school. “Even saying a good morning breaks the ice of any parent,” she said. “Just say, ‘Hey, how’s it going?’ and all of a sudden they become like putty in your hand.”

She gets frustrated by the stereotype that “we as parents don’t care and we don’t know what we want.”

“We do know what we want,” she said, “but no one ever took the time to ask us.”

It pains her now when parents ask when the Chat and Chews will start up again. Glover, too, said he’s been getting inquiries.

Tagoe is searching for another job but still volunteers to help when parents and students seek assistance or information, as many did in the days following Hurricane Sandy. Even though she isn’t being paid anymore, the community’s needs remain.

“I do what I do,” she said. “I’m still there, but not on the grand scale.”