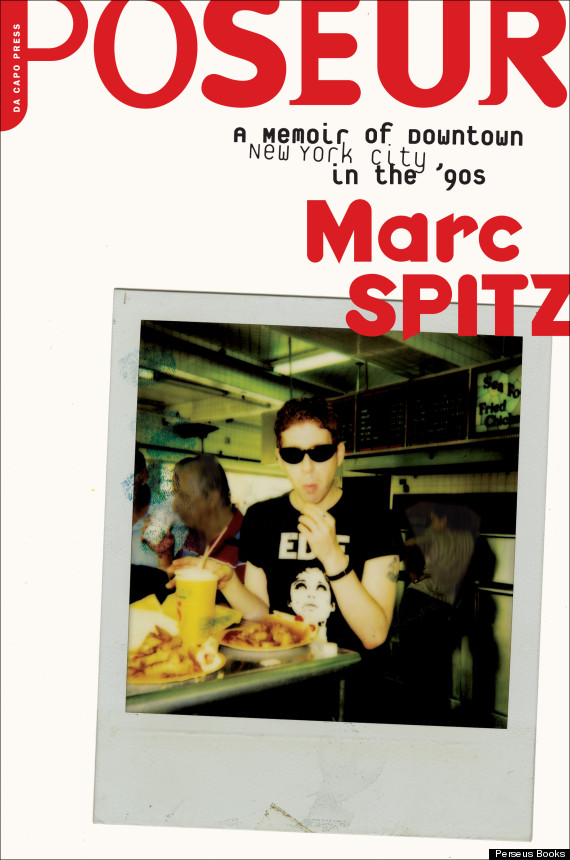

In Marc Spitz's new book, "Poseur: A Memoir of Downtown New York City in the '90s," the author offers a glimpse into the gritty beginnings of his life as a rock journalist. While rubbing shoulders with Courtney Love in the late '80s and running with "It Girl" Chloë Sevigny in the '90s, Spitz lived a dark existence characterized by fame-chasing, heroin addiction and post-punk debauchery that rivaled the antics of the musicians he idolized. From his years as an unpublished poet and playwright to his career as a cover reporter for Spin magazine, the self-deprecating writer chronicles his experience in the underbelly of New York's cultural scene.

Check out an excerpt from Spitz's book below where he dishes on downtown theater, and let us know what you think of the memoir in the comments section.

An excerpt from Marc Spitz's "Poseur: A Memoir of Downtown New York City in the '90s":

“You don’t wanna let the hog onto the picnic blanket there, yes?”

“Of course not.”

Soon the director of Nothing to Say, a pierced, punk Drama Fuck named Owen Kane, was directing my own offering, Cool Baby. It concerns a “fucker” of a poseur writer and his descent into hell, which is filled with even more (and greater) poseur writers, some of them appearing as contestants on a brimstone tinged version of Chuck Barris’s The Dating Game. The audition flyer read in part, “PS: if you feel like you could be Jack Kerouac, Sylvia Plath or Ernest Hemingway, please come and try out.”

Sherman was even harder to beat in late nineties New York than he’d been up at school in the late eighties. At the time I began my “second” play, Retail Sluts, Sherman had cofounded a theater company, Malaparte, with the movie star Ethan Hawke. He had budgets, press, fame, everything Jack and I lacked. But I had one think that Sherman didn’t: a bête noire and the absolute sleep-sucking, spleen-bleeding spite that it engendered in me.

It’s name was... Rent. God, I hated Rent.

It was playing just a few blocks from Andie’s Hell’s Kitchen halfway house. My mother got tickets. Everyone got tickets to that fucking thing, and out of curiosity, I agreed to join her and my sister for a matinee. I did this a few years earlier when Bobbie Poledouris, Zoe’s mother, scored a trio of tickets to see Blue Man Group. I hated those blue cocksuckers too, with their faux naïve expressions and all that hippie circle drumming. It reminded me of being back at The Kitchen, starving and burning, as every tourist offered up his stored-up travel nut to be taken in by these ping-pong-ball-spitting charlatans. If you can tie your dick in a knot or make noise with two garbage can lids, there will always be another load of bus-mooks who will line up to share their wages. It’s enough to make you hate culture. When I was a kid, I saw Little Shop of Horrors at the Orpheum down on St. Mark’s and Second Avenue, and Sandra Bernhard’s ingenious Without You I’m Nothing. Then Stomp came in and put a stranglehold on the place. I still sometimes motivate myself to write a new play by thinking, This is the one that’s going to evict Stomp!

Fuck Stomp (I’ve never seen it).

“I’ve read all about it,” my mother said excitedly, as we took our seats at the Nederlander, just a few paces from where Andie, Jack, and I were living. “It’s just like your life, Marc.”

I’d read all about it too, and the parts that seemed similar to what I’d gone through (struggling for shelter, AIDS panic, the cafés, the heroin, etc.) only made me hate it even more.

The playwright, Jonathan Larson, was getting tons of press for his retelling of Puccini’s La Bohème, but it’s hard to get bohème right, and I was only there because I was hoping he’d misstep somehow. Not that I could tell him this. Larson had also bettered me in my ambition to be a great dead writer. He’d perished from an undiagnosed heart ailment, and it’s only in hindsight, a decade and a half later, that I can finally see that as tragic. Back then I was too bitter, and even though he was unreachable, I was gunning for the poor guy. The lights came down. The head mics filled with spit. My mother’s and sister’s teeth came out in wide, fully entertained grins, and my wildest hopes that Rent would (in my opinion) blow were met.

What a cloying load of pigshit, I thought as I shifted in my theater seat and the spectacle began. What would Antonin Artuad make of Rent? I wish he were here. We’d throw tomatoes. This isn’t the New York City I know—junkies and people dealing with HIV and bills with humor and pluck. There’s no fucking pluck! Artists don’t have pluck! Fuck pluck! This is a fraud! A fraud!

Rent ran forever. Rent won the Tony. Rent, like Shakespeare, Miller, Sondheim, will be revived as long as there are stages. And nobody will ever know, and few will care, that Rent also birthed my career in the thee-ay-tuh. As we filed into the lobby, my mother grabbed me and whispered, “That one guy had a wallet chain, just like yours!” That’s all it took. From that point on, I was a playwright. I would not rest until I got “downtown” right. I would steal it back from Larson like U2 stole “Helter Skelter” from Manson.

“No more fucking Jeopardy, Andie!” I insisted. “I’ve got to finish this play.”

I wrote Retail Sluts in a day and a half in a furious burst of resentment. It concerned a store called Jet Boy, Jet Girl (after the Eton Motello song that Plastic Bertrand sampled for “Ça Plane Pour Moi”). Jet Boy is a store like NaNa in SoHo (although I stole the name Retail Slut from an actual store in Los Angeles) and its staff of fuckups who are all, as I was, pushing thirty: Dommy, a hunky actor who tried to make it in LA before coming back to Jet Boy; Clarence, a gay junkie whose sugar momma buys him Prada and tries to convert him to Christianity and save his soul (by fucking him); and Tony, the manager, who’s so tightly wound, he polices the local playground. All three are stuck wondering why they never made it, why they are clocking in and earning minimum wage, how that places a value on them in an expensive and rapidly gentrifying city, what trouble they can get into with such a miniscule sense of self-worth, and how they both hate and need each other. Once I started writing plays, I began to explore the drama section of bookstores, stealing or simply standing and reading whatever I could before being noticed. Joe Orton and Christopher Durang became my two favorite playwrights, so I made sure to scatter a lot of sex and pop commentary throughout the whole thing in search of the right winking, farcical, and brutal, but still affectionate, tone.

Marc Spitz's "Poseur: A Memoir of Downtown New York City in the '90s" will be released by Da Capo Press on February 12.