On July 25, 1952, in front of a crowd waving American and Puerto Rican flags, Puerto Rico Gov. Luis Muñoz Marin officially raised the Puerto Rican flag for the first time. That day, the constitution — and with it, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico — was put in place. But will this now-highly-debated status endure the test of time?

The commonwealth, officially known in Spanish as the Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, still stands — proudly to some, shamefully to others.

Muñoz Marin was the first governor elected by Puerto Ricans, and he is credited with the creation of this arrangement which has made Puerto Rico part of the United States of America — though not a state.

The establishment of the Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico

Shortly after he received 61 percent of votes and took office, Muñoz Marin tackled the status dilemma. The governor preferred a solution between statehood and independence that would give Puerto Rico sovereignty.

In Washington, D.C., the island’s representative in Congress — Resident Commissioner Antonio Fernos Isern — introduced a bill in March 1950 to the House of Representatives, asking the U.S. for authorization for Puerto Ricans to redact their constitution. Four months later, that bill became U.S. Public Law 81-600, which the people of Puerto Rico voted to approve in a referendum in June 1951.

The constitution was redacted, approved by a constitutional assembly one year later, in February 1952. Then Puerto Ricans voted to approve that constitution in March 1952. It went to Congress for approval, and finally, President Harry S. Truman ratified it on July 3. It went into effect three weeks

“I will raise [the flag] upon the foundation of the free state in voluntary association of citizenship and affection with the United States of America,” Muñoz Marin said on July 25, 1952. “The people will see in it the symbol of its spirit before its own destiny.”

To the sound of the national anthem — “La Borinqueña” — the flag was raised to stand alongside the U.S.’ flag. But the creation of the Estado Libre Asociado hardly solved the debate surrounding the island’s political status.

This Thursday, the Island of Enchantment’s government will celebrate this milestone amid questions of whether the island is closer than ever to become the 51st state to join the union, leaving behind the Estado Libre Asociado.

The hunger for statehood

The debate about the political status of Puerto Rico started decades before the commonwealth came to be. There is much unhappiness with the relationship between the island and the U.S. Many have highlighted the fact that Puerto Ricans can be sent to war at the president’s disposal, but they can’t vote in presidential elections. In addition, Puerto Rico’s representative in Congress can introduce legislation, but he can’t vote on anything.

These, and other factors, have led the statehood movement to grow over the years.

Today, the three main political parties on the island — instead of being divided in terms of liberals and conservatives — are divided by three different visions for Puerto Rico.

The Popular Democratic Party, commonly referred to as PPD by Puerto Ricans due to its acronym in Spanish, is the party in power, with current Gov. Alejandro Garcia Padilla at the helm. Founded by Muñoz Marin 75 years ago, it defends the commonwealth. When it comes to U.S. politics, it has aligned with the Democratic Party.

The New Progressive Party, commonly known as PNP, is the party for statehood. Their highest-ranking official is Resident Commissioner Pedro Pierluisi, a Democrat who has been diligently working on pushing the congressional debate on statehood for Puerto Rico. In terms of U.S. politics, the PNP has a mix of Republican and Democrat members. The most recent high-profile Republican to lead the party was former Gov. Luis Fortuño, ousted by Garcia Padilla.

The Puerto Rican Independence Party — or PIP — has, for decades, demanded independence. They call for the liberation of Puerto Rico, but they have never gotten close to beating the PPD or PNP in elections.

As time goes by, the debate between these parties has intensified. The last administration to lead the country — Fortuño’s — ran on a platform to resolve the status question once and for all. Last year, it arranged a plebiscite to ask the people what status they would prefer. However, this wasn’t the first plebiscite to propose this question, and it will most likely not be the last.

A history of plebiscites

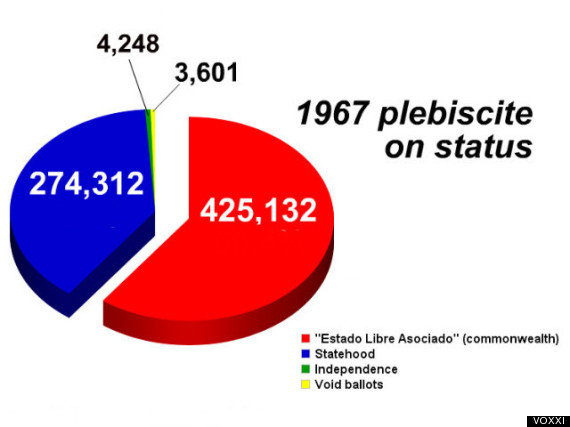

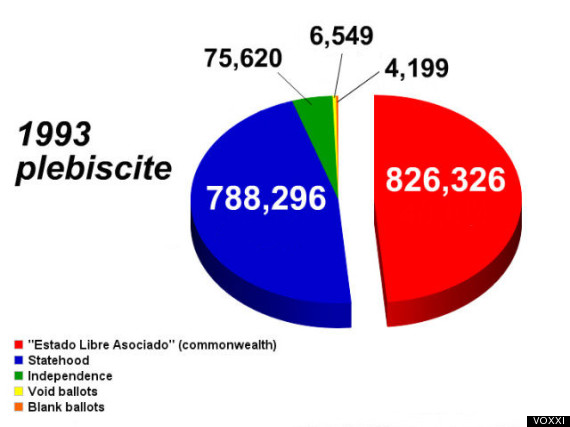

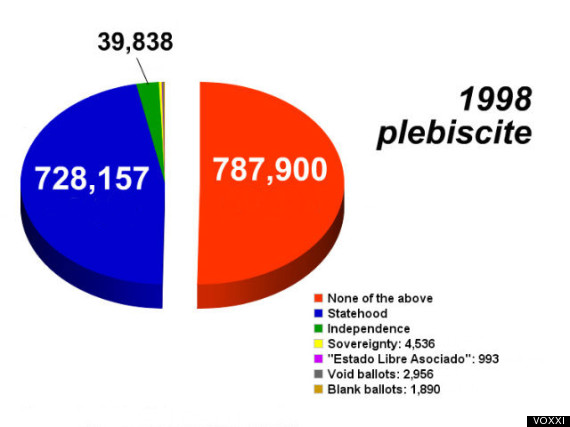

Since 1952, four plebiscites have taken place to ask the people of Puerto Rico their opinion on the island’s political status — in 1967, 1993, 1998 and 2012.

The 1967 plebiscite stands alone in that it has been the only plebiscite approved by Congress. It had three straightforward options: Stay with the commonwealth, become a state or choose independence. This has also been the only plebiscite to take place under a PPD administration.

The 1993 plebiscite was the first of two that took place under Gov. Pedro Rossello’s (PNP) administration. Rossello lost no time in conducting this plebiscite — he had taken office 10 months before Puerto Ricans were consulted. The Estado Libre Asociado prevailed again.

The plebiscite that took place in 1998 — Rossello’s second — was the most controversial one yet.

The reason for controversy was that the definitions provided for the option to keep the commonwealth and the option for sovereignty. The PPD was not pleased with the way the PNP had laid out the options, and took offense at the way the Estado Libre Asociado was described.

- The first column described the commonwealth as a “limited government” that Congress could treat in a way different from the states.

- The second column offered a sovereign state associated with the United States. Puerto Ricans would no longer be born U.S. citizens, though the ones that already held American citizenship could pass that citizenship down to their descendants. The U.S. would renounce all powers in relation to Puerto Rico. A new treaty would be drafted to agree upon Puerto Rico’s role in the international stage, among other things.

- The third column asked the U.S. to welcome Puerto Rico into the union as a state. The governor passionately campaigned for this option.

- The fourth column offered independence.

- The fifth and final column was the “none of the above” option. It was added after the PPD argued the Estado Libre Asociado was not properly represented, and there were no options they could support. The party campaigned for this option — La Quinta Columna — and prevailed.

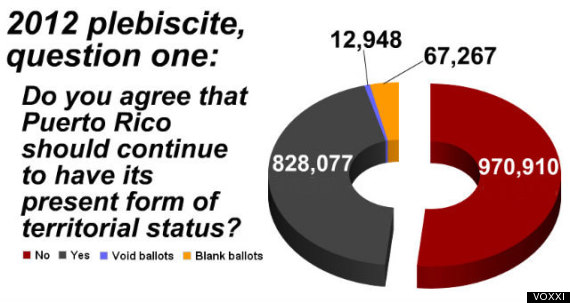

- The most recent plebiscite took place last November, on election day.

Fortuño and the resident commissioner, Pedro Pierluisi, ran in 2008 on the promise that they would get statehood for the island. Three years after they took office, in time for their re-election campaign, plans for the new plebiscite were drafted. Of course, their PPD opponents disagreed with the layout.

This plebiscite asked two questions:

Those supporters of the commonwealth were outraged that the three options from the second question didn’t include the option to vote for the Estado Libre Asociado.

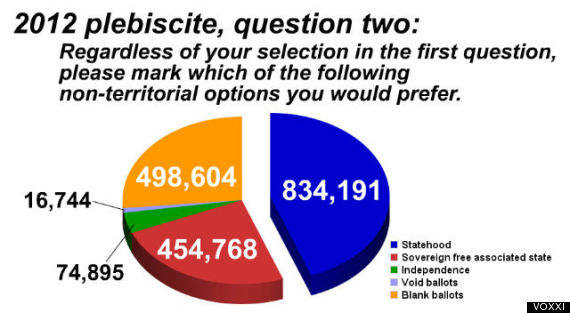

So while Fortuño and Pierluisi campaigned for re-election and statehood, their main opponents at the PPD campaigned for people to leave the second question blank, a strategy that the resident commissioner told VOXXI was “cynical and unwise.” In the end, almost half a million voters left the second question blank. Of the three options, statehood got the most votes.

The first question, asking whether Puerto Ricans are happy with the current status, received a resounding, “No,” thanks to statehooders, those who support sovereignty, independence supporters and others who are tired of the commonwealth.

The future

Pierluisi had two victories on election night: the victory of statehood and his re-election. The challenge was dealing with Garcia Padilla, who — of course — opposes statehood and said nothing would be done to take the plebiscite results to Congress. Pierluisi went ahead and appealed to Congress, regardless.

Backed by a provision in the latest Obama budget, the resident commissioner saw an opening. The president’s budget allows for a U.S.-sanctioned plebiscite to ask people to vote on status once again. Pierluisi has introduced legislation into the House to coordinate for a plebiscite which — this time around — would be a simple matter of voting “yes” or “no” to statehood.

Although Pierluisi’s bill currently has 99 cosponsors — one of them Puerto Rican Rep. Jose Serrano (D-N.Y.) — the other two Puerto Ricans serving in Congress have raised their voices to ask their colleagues to reject the resident commissioner’s bill.

Reps. Nydia Velazquez (D-N.Y.) and Luis Gutierrez (D-Ill.) wrote a letter to House members this week, saying that more than 55 percent of voters rejected statehood — if the ballots left blank in protest, votes for independence and votes for a free sovereign state were added.

“Given the intentionally flawed nature of last year’s referendum, a true process of self-determination should take place in which all the available options are presented to the voters in Puerto Rico,” Gutierrez and Velazquez wrote.

It remains to be seen what will happen to Pierluisi’s bill, since it remains in committee and there has yet to be a hearing on it.

However, with all these developments, this 25th of July, the 61-year-old Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico could be closer than ever to a change.

Originally published on VOXXI as The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico at 61: Closer to statehood?