Pablo Picasso, who was born on October 25, 1881, illuminated much of the next nine decades with his towering, irrepressible genius. In 1996, 23 years after his death, Arianna Huffington finished Picasso: Creator and Destroyer, a biography that took the measure of his extraordinary accomplishments while exposing the dismaying truth about his predatory approach to relationships. In the book's preface, featured here on the occasion of what would have been Picasso's 132nd birthday, Huffington summarizes her chief insights into Picasso the artist and Picasso the man. Scroll down for a slideshow of the artist's work,which was on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York last year.

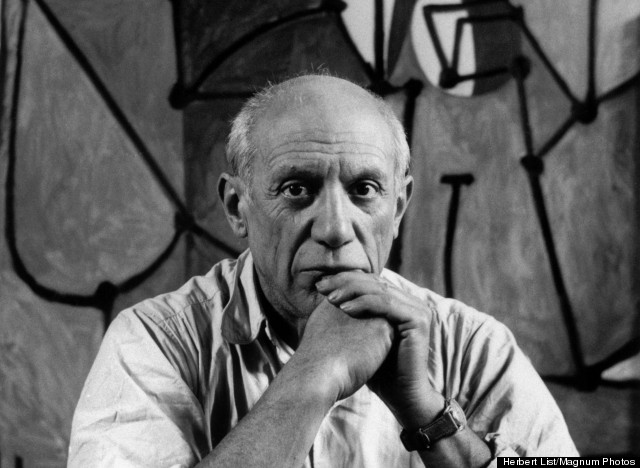

Pablo Picasso in front of The Kitchen (La cuisine, 1948) in his rue des Grands-Augustins studio. Photo: Herbert List/Magnum Photos

From the preface of Arianna Huffington's Picasso: Creator and Destroyer (1988):

Surprise was a key characteristic of Picasso’s art, and it was the most persistent emotion evoked in me during the years this book has been in the making. I was brought up, like so many of my generation, to see Picasso as the most extraordinary, the most compelling, the most original, the most protean, the most influential, the most seductive and certainly the most idolized artist of the 20th century. After a day at the massive Picasso retrospective at the Grand Palais in 1980, I walked the streets of Paris as if a physical act were needed to absorb the boundless energy that had engulfed me from the nearly one thousand Picassos that made up the exhibition—the paintings and the drawings, the sculptures, the prints and the ceramics. The legend of Picasso, the sorcerer and magician, was confirmed; but buried in admiration, fascination and sheer physical exhaustion, there was an uneasy feeling.

Two years after the retrospective I began work on this book. Five years and countless surprises later, the Picasso of legend seemed like the fantasy hero of a collective act of make-believe compared with the Picasso I came to know and have tried to recreate in the pages that follow. I felt like Henry James brought face to face with “a jewel brilliant and hard...It twinkled and trembled and melted together; and what seemed all surface one moment seemed all depth the next.” The man who appeared to be a towering creative genius one moment turned into a sadistic manipulator the next. What seemed a life guided by burning passions—for painting, for women, for ideas—seemed a moment later the story of a man unable to love, intent on seduction not in the search for love, not even in the desire to possess, but in a compulsion to destroy. “I guess,” he said once, “I’ll die without ever having loved.”

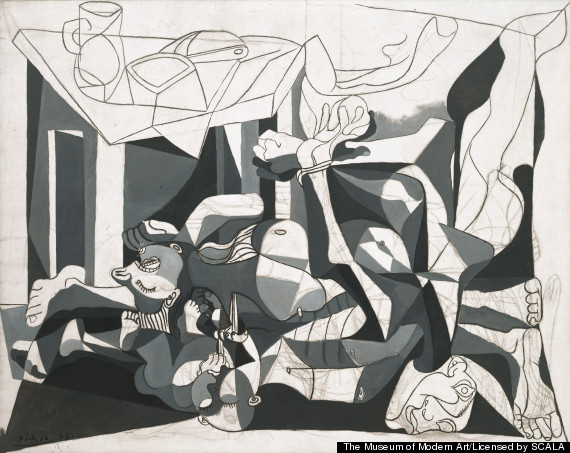

It was, in fact, this struggle between the instinct to create and the instinct to destroy that was at the heart of this book. The evidence of Picasso the creator is vast and glorious, his prolific creativity almost mythical. He stamped his images and his vision not just on the world of art but on the whole of the twentieth century. The evidence of Picasso the destroyer is tragic. The suicides of his second wife, of his grandson and of Marie-Thérèse Walter, his mistress of many years; the psychic disintegration of his first wife; the nervous breakdowns of Dora Maar, the brilliant artist who was his mistress during the time of Guernica—all are part of a formidable list of casualties among those who came too close to the destructive fallout of his personality. There was a great deal more evidence of Picasso the destroyer which I came upon unexpectedly, and at first reluctantly, in the course of the hundreds of interviews that I or one of my research assistants conducted in Paris, Barcelona, the South of France or wherever we could find those who knew Picasso during his life and who, either inadvertently or because they had not been blinded by the legend, revealed facts that fleshed out the dark side of his genius.

The Charnel House (Le charnier). Grands-Augustins, Paris, 1944–45. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 199.8 x 250.1 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Mrs. Sam A. Lewisohn Bequest (by exchange), and Mrs. Marya Bernard Fund in memory of her husband Dr. Bernard Bernard, and anonymous funds, 1971. © 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Facts have their own undeniable authority. But they do not in themselves make a life or a biography. They are woven together by the cluster of convictions, emotions and ideas that, knowingly or unknowingly, for good or ill, form the biographer’s vision of life and the world; I tried throughout to be conscious of mine. In telling Picasso’s story I have been guided by a statement of his I found tucked away in a French book; I translated it and kept it framed on my desk until its message began to feel like Picasso’s personal instructions to me: “What is necessary is to speak about a man as though painting him. The more you put yourself in it, the more you remain yourself, the closer you get to truth. To try to remain anonymous, out of hatred or respect, is to do the very worst—to try to disappear. You’ve got to be there, to have courage; only then can it become interesting and bring forth something.”

I put myself in it until I found that he stirred in me all the emotions present in an intimate relationship. I was seduced by his magnetism, his intensity, that mysterious quality of inexhaustibility bursting forth from the transfixing stare of his black-marble eyes as much as from his work. I was both fascinated and appalled by his unparalleled power to invent reality in his life no less than in his art and to persuade his women to inhabit the reality he had created, however big the gulf between it and the truth. “I love you more each day, you are everything to me, I will sacrifice everything that I have for you for our love for always,” he wrote to Marie-Thérèse at the same time that he had chosen to set up house with Francoise Gilot. In search of an explanation for his compelling attraction, I went back to the original Spanish tales of Don Juan and the Indian myths of Krishna, the lover-god for whose love, however brief and shared by many, women would abandon everything; and I understood that Picasso was for the women and for many of the men in his life both the irresistibly sensual and seductive Don Juan and the divine Krishna who promised access to a heightened reality. As a result, many became addicted to him and were prepared to pay—even with life and sanity—the high price of their addiction.

I was struck by his instinctive brilliance in using publicity to build his celebrity and then his legend. “A picture lives only through the one who looks at it,” he said. “And what they see is the legend surrounding the picture.” I loved—admittedly with a certain wryness—his contradictions: the man of the world full of peasant superstitions; the man of the people who spent millions to keep himself in bohemian splendor; the monumental egoist who became a proud member of the Communist Party.

But there was more to him, and darker. I was chilled by the way that he fought throughout his life the deepest existential battles of our century until he was ultimately destroyed by them. This realization was for me the turning point of the book. I suddenly saw that Picasso’s life was not just the life of one of the most gifted artists who ever lived; it was not just the life of an extraordinary and extraordinarily complex man who would have been fascinating even if he had never held a paintbrush; it was, in a very real sense, the twentieth century’s own autobiography. And it was by mirroring, reflecting and epitomizing our century and all its torments both in his life and in his art that he became a culture hero and the legendary personification of our tumultuous times.

A champion and troubadour of our century’s longing to explore the limits of human sexuality, he exuded raw sexual power, free of all restraint, at the same time that he vilified women as devouring monsters. Another profound way in which he mirrored our century was in his deep ambivalence toward God and the divine. He would push religion out the door and watch it come back through the window. He trumpeted his atheism at the same time that he identified with the crucified Christ and returned to this theme in his work during all the great ordeals of his life. He was the chief witness to the darkness and inhumanity of the century, a century dominated by political ideologies in the name of which unspeakable atrocities were committed. In his life he endorsed one of these ideologies by joining the Communist Party with great fanfare in 1944. In his work he threw the glaring light of his genius on the depths of evil in man and in our times. Like Freud, that other great reporter of our discontents, he saw deeply and accurately the tormented sexuality, violence, and pain sheltering beneath the leaky roof of civilization. That was his triumph.

His tragedy was that while consecrating destruction in his art, he practiced it relentlessly in his life. Terrified of death and convinced that the universe was evil, he wielded his art as a weapon and meted out his rage and his vengeance on people and canvases alike. “A good painting,” he explained, “ought to bristle with razor blades.” And a good relationship too.

The only woman who survived the razor blades and then went on to flourish, both as a human being and as an artist, was Francoise Gilot. As soon as I began work on the book, I asked to interview her. She told me that she did not want to reopen the Picasso chapter of her life and declined. Two years later, she and her husband, Dr. Jonas Salk, came to spend a weekend with me at my home in Los Angeles. It was a weekend that was the beginning of an amazing journey of discovery. She had suddenly decided, as a result of her “inner guidance,” she explained, to talk to me and reveal the many facts and insights that she had left out of her own book on Picasso, published while he was still alive and while, she felt, her children were still too young to be exposed to the full truth. Over the next year I spent many days and nights talking with her in Los Angeles, in La Jolla, in New York and in Paris. She not only re-created for me in great intimacy her years with Picasso, but gave me access to letters, trial files and photographs which greatly enriched my understanding of those years. And she urged me not to write about the dead Picasso, symbol and legend, but to engage in a personal encounter with the man and the artist: “It should not be a biographer writing at arm’s length about Picasso,” she told me, “but you, Arianna, in a living, present relationship with him.”

Reclining Woman Reading (Femme couchée lisant), 1960. Oil on canvas. 130.2 x 196.2 cm. Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Museum purchase, The Benjamin J. Tillar Memorial Trust. © 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Tom Jenkins

There were certain key encounters which strengthened that sense of being involved in a living relationship. Maya Picasso, Picasso’s daughter by Marie-Thérèse Walter, was one of them. “These are my most important Picassos,” she said in her apartment on the Quai Voltaire, pointing to her son and daughter, who had just walked into the living room. Picasso had refused ever to meet his grandchildren, and as I looked at them, I felt a pang at how much vibrant life he had separated himself from during his last years of isolation and despair.

In Mougins, not far from where Picasso died, lives Ines Sassier, who had been Picasso’s maid, housekeeper and confidante for more than a quarter of a century. She had not answered any of my letters or phone calls, and it was only when I arrived at her doorstep that she finally agreed to talk to me about the man who had become her life and who for many years painted her portrait as a gift for her birthday. Listening to her relive her life with Picasso was deeply moving—for both of us. As she was walking me to my car late one evening after our last meeting, she took the knitted shawl she was wearing and draped it around my shoulders. “You need it to protect you from the cold night air at this time of year,” she said. “I’m used to it.” In that one gesture, I experienced all the nurturing qualities she had brought to Picasso and understood what he meant when he said once, “I owe her the whole of my life.”

“You keep the shawl,” Ines said, when we got to the car. I did not protest. “And you keep my earrings,” I said, giving her the earrings she had admired earlier. The exchange was symbolic of an infinitely more important one that had taken place over the past few days.

There were many others who fleetingly, or for years, had been close to Picasso and who provided much of the personal knowledge and intimate detail I needed if I was to have any hope of turning the man who had become a symbol into a living reality: Maitre Bacqué de Sariac, his lawyer during many pivotal events in his life, including the lawsuits he brought against Francoise Gilot’s book Life with Picasso and her struggle to legitimize her children, Claude and Paloma; Geneviève Laporte, still convinced in her old age that she was Picasso’s only true love; the Countess de Lazerme, who had provided refuge for him in her castle in Perpignan; Kostas Axelos, the Greek existentialist philosopher with whom Francoise Gilto was having a relationship at the time she left Picasso; Maurici Torra-Bailari, a friend of his youth and a frequent visitor in his old age; Hélène Parmelin, one of the few intimates of the last twenty years of the last twenty years of his life; his barber, the only man Picasso trusted enough to let him cut his hair—a major honor, since he believed that in the wrong hands, his hair trimmings could be used to control him; his gardener, living in the South of France in a modest home filled with Picassos—all these and many others provided a foundation of fact and understanding on which I began to build the book.

The more I discovered about his life and the more I delved into his art, the more the two converged. “It’s not what an artist does that counts, but what he is,” Picasso said. But his art was so thoroughly autobiographical that what he did was what he was. His was a destiny that transcended his personal fortunes and misfortunes. Re-creating it has turned out to be not only a personal but a passionate encounter with a man whose life spanned ninety-one years of an extraordinary journey of creation and destruction.

All images are from the "Picasso Black and White" exhibit previously on view at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City.