We did it, America! Our broke, dysfunctional government has somehow pulled itself together long enough to soundly defeat powerful, wealthy Wall Street, turning the financial industry into a squeaking little gerbil. At least, that is what finance wants you to think.

Politico's Ben White seems convinced: On Thursday, he declared victory in what he described as Washington's tireless quest to tame Wall Street after the financial crisis.

"In 2009, Washington went to war against big Wall Street banks hoping to blow up the kind of high-risk, high-reward strategies that helped spark the financial crisis," White wrote. "Five years later, that war is largely over. And Washington won in a blowout."

This is wrong on many levels, and dangerously so. Banks are vigorously waving the white flag in hopes that we will forget how they are by some measures bigger than ever, and at least as powerful as ever in what is still an ongoing war with Washington -- a war they actually started.

"That's ridiculous," Stanford professor Anat Admati, co-author of The Bankers' New Clothes, emailed when asked about White's story. "Nice narrative but false."

"To think that the war is over is just contradicted by the facts from one end of Washington to the other," said Dennis Kelleher, chief executive of Better Markets, a Washington nonprofit group pushing for financial reform. Just hours after White's piece was published on Thursday, Kelleher posted a rebuttal to it on The Huffington Post.

Kelleher was actually quoted in White's piece because Kelleher believes, as do most humanoids with eyeballs, that at least some things on Wall Street have changed since the crisis.

White used Kelleher's quote to defeat a straw man: It is really hard to find anybody who believes that absolutely nothing has changed on Wall Street. Banks have been ordered to hold more capital for protection against future crises. They are shedding some of their riskier businesses. They are trimming down, in other words. That is a good thing, given how bloated and powerful the financial industry got before the crisis.

But the financial industry is still too bloated and powerful. That is one big thing that has not really changed much since the crisis. The biggest banks are bigger than ever, with more concentrated power, and risk, than before the crisis.

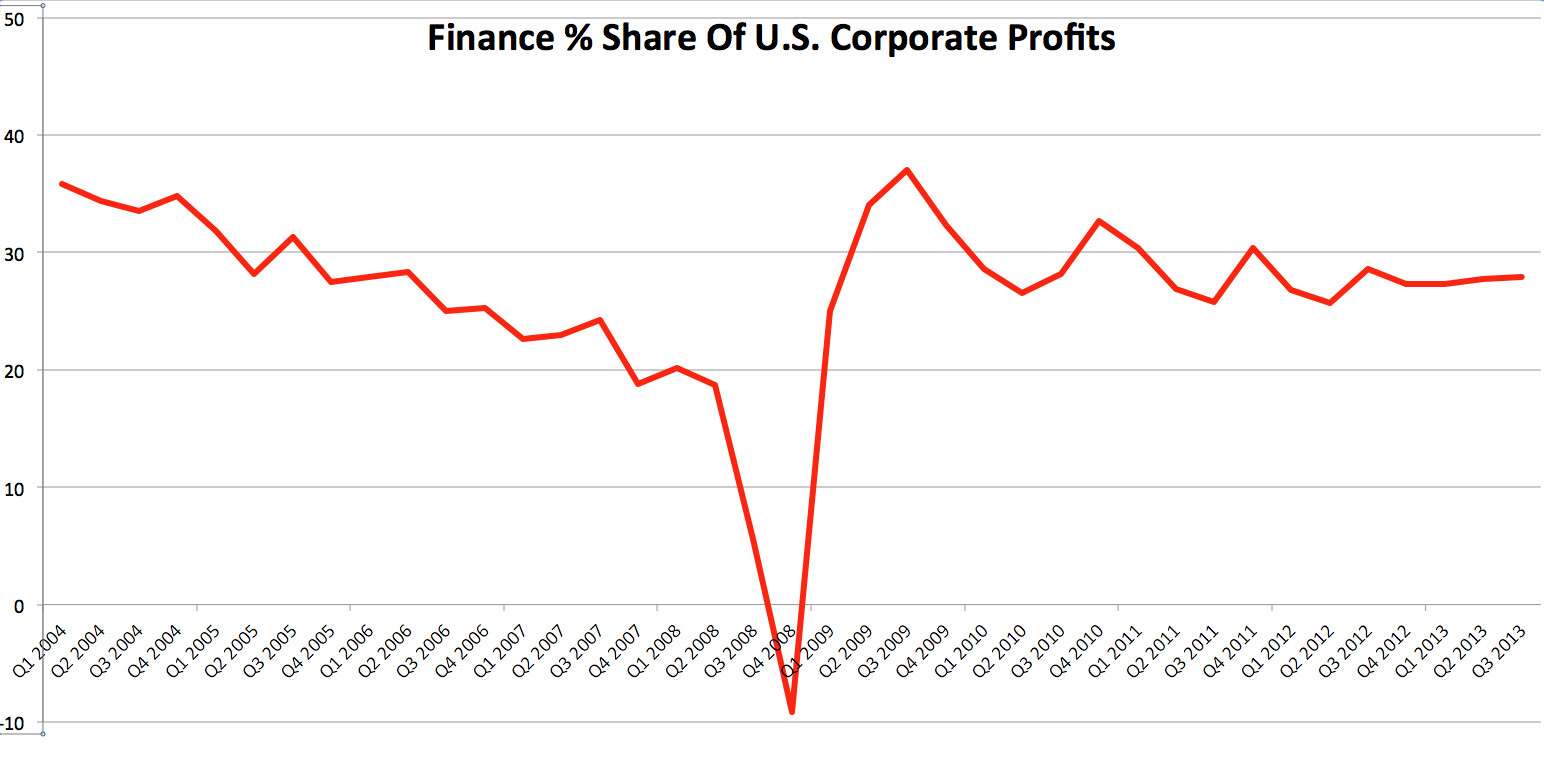

White noted that bank profits from certain risky activities have fallen since 2007. And yet they have made up for it pretty well: Finance took in about 27 percent of all corporate profits in the U.S. in the third quarter of 2013, a bigger percentage than in 2007, according to a HuffPost calculation using figures from the Commerce Department.

Finance's share of corporate profits is lower than a recent peak of 37 percent calculated by HuffPost for the third quarter of 2009 -- a time when banks were raking in cash while the rest of the economy suffered. But the industry still hoards a far bigger share of the economy than is justified by what it actually does for the economy: Finance adds only about 12 percent of the value of gross domestic product, based on Commerce Department figures, while pulling in more than a quarter of the profits.

Data via the Department of Commerce

Goldman Sachs' fourth-quarter 2013 profit report stood out to White as proof of his thesis. The bank's net revenue in trading bonds, derivatives, currencies and commodities tumbled to $9 billion last year from $16 billion in 2007, according to White.

But that decline is not entirely, or even mostly, Washington's fault. It is cheating to compare the money banks made in credit trading just at the top of the wildest credit bubble in modern times to the aftermath of that credit bubble. Of course banks are going to earn less shuffling those pieces of paper around now than in the pre-crisis era, because many of them -- subprime mortgage derivatives, in particular -- are no longer traded in any significant way. Of course banks are going to take fewer risks -- meaning less profit -- just after teetering on the edge of the abyss because of their earlier risk-taking.

And it should hardly be shocking that banks might struggle to turn a profit during the long, slow slog that has been this economic recovery, a recovery often hampered by Washington ineptitude. (That is one way, I guess, you could realistically argue that Washington has indeed defeated Wall Street.)

Mostly, Wall Street has defeated itself: As White pointed out, JPMorgan Chase's own "London Whale" debacle helped convince regulators to tighten the fetters on bank risk-taking last year with a tougher-than-expected "Volcker Rule." The credit bubble that banks helped inflate left a debt overhang that has taken years to whittle away, leaving little demand for new loans in the meantime.

And yet, somehow, despite all of these hurdles -- loan demand dead in the water, risk-taking curbed, higher capital requirements, the cruel words of President Barack Obama, Occupy Wall Street and Huffington Post hacks -- banks have continued to rake in the profits.

The Federal Reserve has helped, by keeping borrowing costs low and helping fuel rallies in stocks, bonds and other risky assets. And of course the banks continue to take some profit-making risks, because that is just what they do. JPMorgan, once thought to be the best-managed bank in the known universe, vomited up $6 billion in just a few months in 2012 betting on credit default swaps.

A new study by economists from the University of Washington and the University of Michigan found that the banks that took bailout money after the crisis took more risks with that money, often in ways that were perfectly acceptable to regulators.

"These banks appear safer according to regulatory ratios, but show a significant increase in volatility and default risk," the study's authors wrote.

Despite falling into disrepute, banks still have political power and a vast lobbying army. Behind the scenes, even as some of us declare victory and move on, banks are continuing to work new loopholes into the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation and its most hated provision, the Volcker Rule.

White's piece reads a lot like an effort to persuade the Elizabeth Warrens and David Vitters of the world that their work is done, that there is no need to punish these poor banks even more by breaking them up into still-smaller, more manageable pieces. Let's keep the champagne corked.