This piece comes to us courtesy of Education Week, where it was originally published.

An Illinois woman has turned the lessons she learned in her recovery from her own childhood sexual abuse into a nationwide push to pass state laws that require student lessons and teacher training about the issue in public schools.

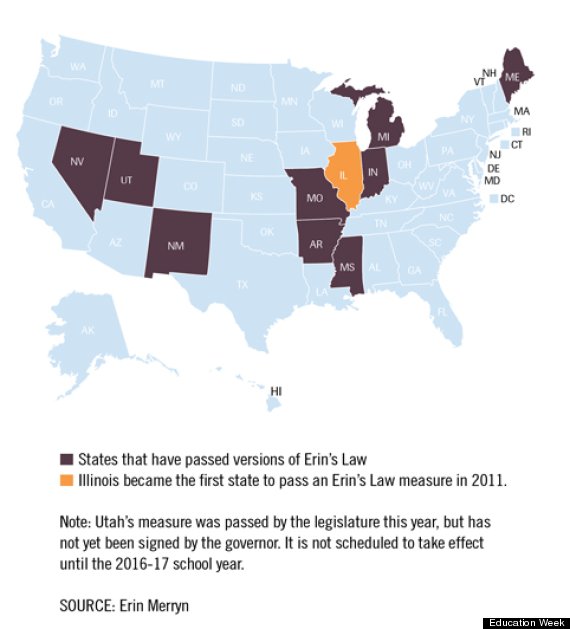

Starting in her home state in 2011, Erin Merryn has successfully pushed for passage of a so-called "Erin's Law" in 10 states, and she expects that number to grow as 26 have considered or are considering similar bills in their 2013 and 2014 legislative sessions.

The bills, which vary state by state, generally require age-appropriate instruction for children as young as prekindergarten on preventing, recognizing, and reporting sexual abuse. They also either allow teachers to count training on sexual abuse toward continuing education requirements or mandate such training for all public school personnel.

Schools are a natural place for young children to learn what sorts of behaviors by adults are appropriate, Ms. Merryn said. And teachers, who often form trusting relationships with students, will be better equipped to intervene in abuse situations if they recognize common warning signs masked as behavior issues, she said.

"We have to teach kids the difference between a safe touch and an unsafe touch, a safe secret and an unsafe secret," Ms. Merryn said. "Without it, kids get one message, and it's from their perpetrator who is victimizing them."

Experts say sexual abuse-prevention programs in public schools have fallen by the wayside in recent years in favor of new efforts targeted at issues like bullying. And the sexual abuse-related programming that remains is often taught to high school students and not in earlier grades.

Ms. Merryn, 29, suffered two periods of sexual abuse as a child growing up in a Chicago suburb. After she was raped at 7, she shoved her hand through a window and became disruptive at school, she said.

School leaders matched her with a social worker, Ms. Merryn said, and created an individual education plan to address her behavior. "But they weren't asking the important question: 'Erin, why did you do this?' " she recalled. "I am confident I would have told."

Statistics and Symptoms

Various analyses of federal data estimate that around one in five girls and 1 in 20 boys are sexually abused as children. Rates are difficult to pinpoint because many incidents go unreported and not every report is confirmed, researchers say.

Data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services show that 16.6 percent of the more than 2 million child-abuse and--maltreatment reports in 2012--the most recent year with data available--were made by education personnel.

But while teachers are required under state and federal laws to report suspicions of sexual abuse, many fail to do so, said David Finkelhor, the director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire in Durham.

"It's easy in a school environment, unlike, say, a medical environment, for a teacher or somebody who recognizes something to think it's really somebody else's responsibility to do something," he said. "There's kind of a diffusion of responsibility that can happen."

In addition, teachers get inconsistent, often minimal training in how to make reports, and sometimes fail to recognize the signs of child sexual abuse, Mr. Finkelhor said.

Children who have been sexually victimized often demonstrate sudden changes in behavior at school, such as social withdrawal, aggression, or constant crying, said Brigid A. Normand, a program-development manager for the Seattle-based Committee for Children, a nonprofit organization that develops programs to address children's mental and emotional issues.

"Behaviors teachers see in children are always saying something," said Ms. Normand, who is working on professional-development materials to help teachers recognize signs of abuse and mistreatment in students. "We need to teach [educators] to reframe behaviors they're seeing to ask themselves, 'I wonder what's going on with this child?' "Behaviors like those Ms. Merryn demonstrated after her own abuse are common, child advocates say. Some victims also masturbate compulsively, wear extra layers of clothing out of an instinct for self-protection, or draw pictures that are unusually sexual for their age, Ms. Normand said.

The Committee for Children's new materials will help teachers learn how to have open, nonleading conversations with students if they suspect a problem, and how to "pool knowledge" with other adults in a school if they see red flags that may trigger a report, Ms. Normand said.

Ms. Merryn, who spoke up about her own situation only after she learned her sister was also being abused, said classroom lessons on the subject give children open doors to report abuse if it is occurring.

"We need to give kids a voice and the tools to tell," she said.

An analysis by the National Conference of State Legislatures that was last updated in 2013 showed laws in Vermont, California, and Texas that predate Erin's Laws efforts. And many districts implement programs on their own.

Prevention Efforts

A study that Mr. Finkelhor co-authored with other researchers from his university and the University of the South, which was published in March in the International Journal of Child Abuse and Neglect, found that few young children are taught about sexual assault and abuse in schools. Of 3,391 respondents to a national phone survey of children ages 5–17, 21 percent reported having participated in a prevention program related to sexual assault, and 17 percent said they'd participated in such a program in the past year. Of respondents ages 5-9, 9 percent had participated in a sexual assault-prevention program, and 7 percent had done so in the past year.

In comparison, 65 percent of respondents reported having participated in bullying-prevention efforts.

A task force assembled in Illinois to design its version of Erin's Law found that the state mandated sexual-abuse discussions only in its secondary schools. That's too late for many students, experts said, because sexual-abuse rates peak at earlier ages.

While some states that have adopted Erin's Law allow parents to opt out of the lessons for their children, most concerned parents change their minds when they study the materials and see that they are not graphic or overtly sexual, said Jennifer Wooden Mitchell, a co-president of Child Lures Prevention/Teen Lures Prevention, in Shelburne, Vermont.

Utah's New Law

Utah's legislature--the most recent to act--passed an Erin's Law bill on March 12. It will go into effect in the 2016-17 school year if it is signed into law by Gov. Gary R. Herbert, a Republican. A spokesman for the governor said his office is reviewing the bill to determine if he will sign it.

The Utah bill requires schools to use instructional materials approved by the state board of education to provide prevention training to school personnel and parents. It makes student lessons optional and subject to parental approval. Utah state Rep. Angela Romero, a Democrat and a sponsor of the bill, said she proposed it after reading about Ms. Merryn in People magazine.

Ms. Merryn said the biggest objections to the bills are from state lawmakers who don't want to impose additional mandates on schools and those who fear the programs will create a cost burden for districts.

Illinois' task force acknowledged the burden of adding a mandate without new funding in its report. Materials and training, offered by a variety of third-party groups, carry varying costs. But Ms. Merryn said much of the programming can be financed by grants and led by current employees, such as nurses and social workers.

"You can't put a dollar amount on a child's life," she said.

Coverage of school climate and student behavior and engagement is supported in part by grants from the Atlantic Philanthropies, the NoVo Foundation, the Raikes Foundation, and the California Endowment. Education Week retains sole editorial control over the content of this coverage.