About 40 percent of the developed world's adults have gotten more schooling than their parents. But the number is slipping in some countries, raising concerns that societies will become less inclusive for younger generations.

This year's Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s annual education report, released Tuesday, outlines an array of education statistics from the world’s most developed countries. While the report finds that educational attainment has increased overall, it questions whether this trend will continue for younger generations.

The report takes a deep look at intergenerational educational mobility, or whether a person's educational attainment is higher than his or her parents. While about 40 percent of people aged 25 to 64 are more highly educated than their parents, this number appears to be dropping in some places. About 16 percent of those aged 25 to 34 have lower levels of educational attainment than their parents, compared with 9 percent of those aged 55 to 64. Most people have the same level of educational attainment as their parents.

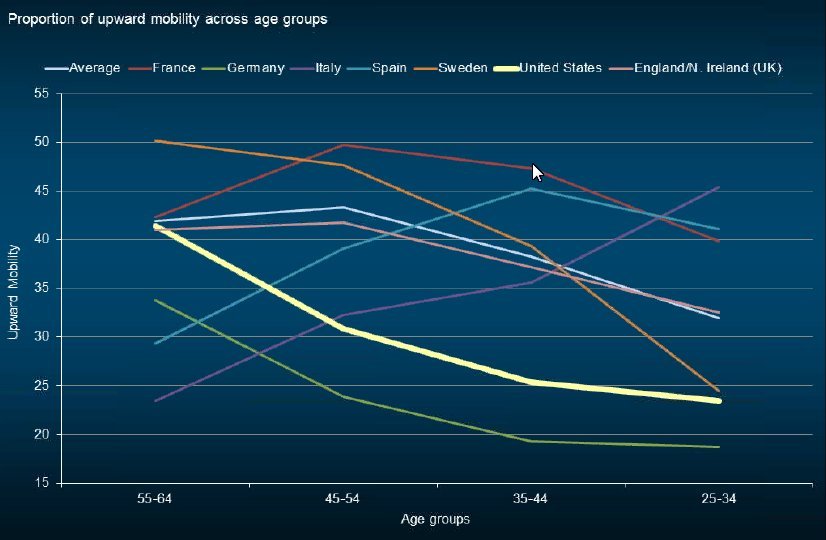

The graph below, created by the OECD, shows how educational mobility is decreasing around the world:

The report sounds the alarm on the potentially slowing of educational mobility.

“When the engine of social mobility slows down, societies become less inclusive,” says the report. “These data suggest that the expansion in education has not yet resulted in a more inclusive society, and we must urgently address this setback.”

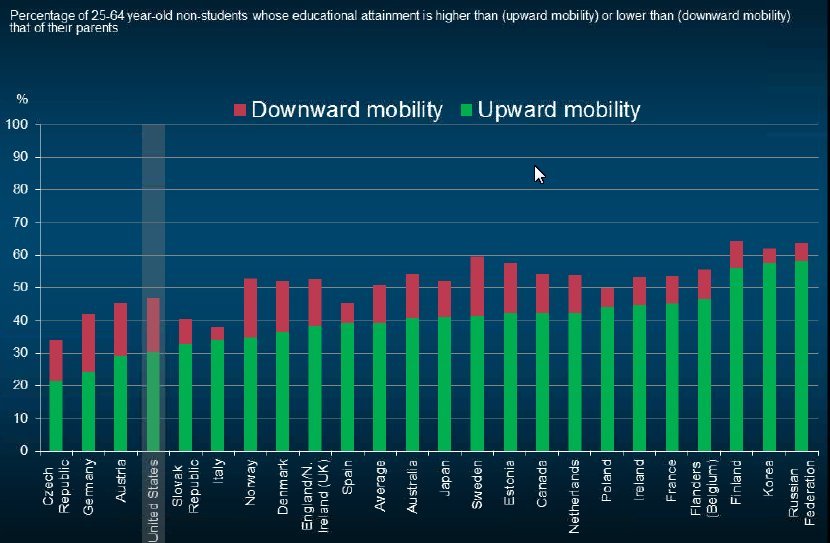

Rates of educational mobility differ starkly by country. In Korea, for example, educational mobility is high, especially when compared with the United States, as shown in the graph below. However, that gap may be attributed to the fact that parents in Korea had much lower levels of educational attainment to begin with, Andreas Schleicher, OECD director of education and skills, pointed out on the phone with reporters.

“Given the U.S. has already many parents with a university degree, the possibilities for upward mobility are more limited than Korea, where many of the older generation did not have a university degree,” said Schelicher. “But still, that only explains part of the variation.”

The report found no connection between higher education and educational mobility. A number of countries had high levels of equitable access to higher education, with low educational mobility rates.

“Equity and access does not in itself guarantee a higher degree of mobility,” said Schelicher.

The graph below displays this phenomenon:

The report explored the connection between educational attainment and health, civics and trust.

“We are interested not only in economic outcomes of education and skills, but also social outcomes,” said Schelicher.

As such, the report found that better educated individuals were more likely to report that they are in good health, and that they have high levels of interpersonal trust. They were also more likely to volunteer, and to express the belief that they could make a difference in the political process and government.

“Thus, societies that have large shares of low-skilled people risk a deterioration in social cohesion and well-being,” the report concludes.