Three years ago this week, Zuccotti Park in downtown Manhattan went from being a place bored office workers went for a cigarette break to the center of Occupy Wall Street.

Today the protesters are long gone, and the public disgust with the financial system that the movement inspired and embodied has faded. But Occupy's effects live on, in the way we talk and think about the American economy, and in the continued work of a core group of activists.

Occupy gained prominence and a following by focusing its efforts on concrete space, but its most obvious legacies are largely ambient and linguistic: Today, 45 percent of Americans are dissatisfied with their ability to get ahead by working hard. In 2008, just 31 percent felt the same way. The ubiquity of the phrase "99 percent" spiked with Occupy’s protests. And it’s hard to argue that the enduring, derogatory use of “the 1 percent” is not the group’s doing.

Introducing Americans to a dramatically different way to talk about inequality is a big achievement. And while much of the change over the past six years in how Americans view the rewards of work is due to the recession (hello, falling household incomes), giving that shift a way to express itself is impressive.

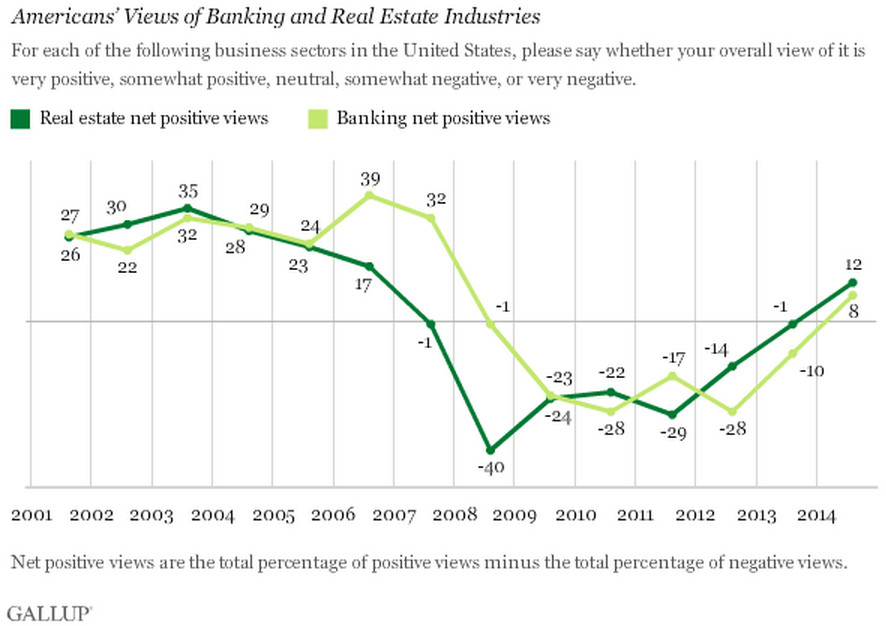

Where you won’t find Occupy’s legacy is in American attitudes toward banks. Despite its initial aim, Occupy did not spark continued, mass disgust with the financial industry among the U.S. public. A Gallup poll shows that American’s now have net positive view of banks:

Occupy Wall Street may have had a short-term effect: From mid-2011 to mid-2012, Americans' already negative view of banks got marginally worse. The drop was not sustained, and its size was very minor compared to the drop caused by the global financial crisis.

How American’s feel about banks isn’t really even the best way to judge Occupy. Its goals were always both bigger (changing the dialogue about the American economy) and smaller (specific policy proposals and concentrated activism) than just getting people upset at one industry. Occupy could be the rhetoric of the 99 percent and the 1 percent (or 0.1 percent), and it could be Occupy the SEC with a scalpel-sharp 325-page, 301-footnote comment letter on the Volcker Rule.

The wonkier legacy of Occupy can be seen in things like a Senate hearing Wednesday afternoon called “Who is the economy working for? The impact of rising inequality on the American economy.” Or the determined, complex work of Strike the Debt, which just bought and canceled $3.9 million in debt from students of a for-profit college. Since 2012, it has wiped out $15 million in medical debt.

Occupy’s legacy being about something other than the banks may be for better. Popular outrage against the financial system -- as cathartic and necessary as it was -- may have outlived its use a vehicle for change. Credit to Occupy Wall Street for building more durable forms of activism at the height of its popularity. Occupy’s real but limited success shows just how hard a fight they picked.