Co-authored by Ellen Dobbyn-Blackmore

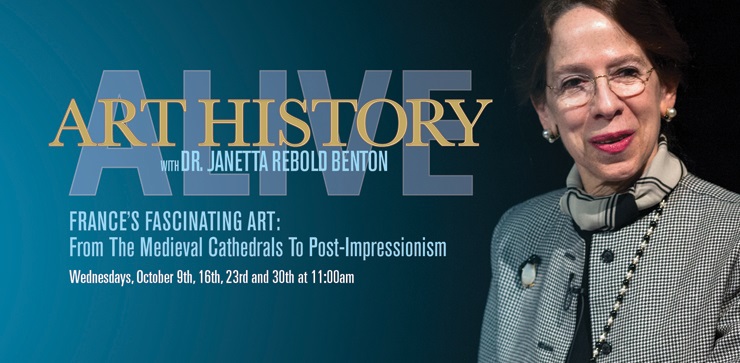

Dr. Janetta Rebold Benton, Distinguished Professor of Art History, Pace University

photo by Kevin Yatarola

Dr. Janetta Rebold Benton is currently giving a series of lectures titled Art is Alive at the Michael Schimmel Center for the Arts in lower Manhattan. (A word to the wise: don't miss it) She holds advanced degrees from such universities as Harvard and Brown, is a Fulbright Scholar, is the author of many books and articles, has taught and lectured around the world; her career is impressive by anyone's standards. Her most recent book is Handbook for the Humanities, a collaboration with Robert Di Yanni. While learned in all aspects of art history, she is truly an internationally renowned expert in medieval art.

Dr. Rebold Benton agreed to meet with us at the Metropolitan Museum of Art recently and knowing what an expert she is, we were thrilled. We spent a long time with her that day in conversation while wandering among the priceless treasures. We opted to go straight to the medieval collection and soon discovered that the down to earth professor, who insisted that we call her Janetta, is herself as much a treasure as anything one might see at the Met. Our conversation covered a wide range of topics and as we stopped before pieces that caught our eyes, we were treated to Janetta's encyclopedic knowledge of all things medieval. We did not expect that this diminutive, soft spoken woman, so conservative in appearance would be such a delightful wit. Her sense of mischief was most readily apparent when discussing medieval creatures.

Janetta Rebold Benton: This is the story of Jonah and the Whale. Whales were obviously not known firsthand. It looks like a curly serpent. It's a prime example of depicting animals without firsthand knowledge.

Ellen Dobbyn-Blackmore: Which happened fairly often. In one of the Unicorn tapestries there's an argument about a wolf. Somebody said it was a hyena and another said it was a wolf. The whole point was that somebody would be drawing this who had never seen the animal.

JRB: The Medieval Bestiary is a book of beasts that was very popular in the 12th and 13th centuries throughout Western Europe and it was illuminated. I just gave a paper about this in Russia. The sources of information are not natural observation. You repeat what earlier authors have said. You do not verify. Instead you replicate and that included things that would have been so simple to correct as in, does the weasel conceive through the mouth and give birth through the ear, or does it, as skeptics argue, conceive through the ear and give birth through the mouth. They could have figured that one out. Elephants were said not to have knees and had to sleep standing up. It could have been verified through simple observation or common sense. There was one creature said to be a cross between an ant and a lion. A hard merger.

Andrew Blackmore-Dobbyn: They didn't copulate easily.

JRB: The birth was even more difficult depending on which one gave birth to it. There were menageries during the Middle Ages which was a symbol of great wealth and ability to not only afford it, but also to be able to maintain the animals. Those menageries did include exotic, imported animals. Once could have access to an actual lion.

The question of whether or not one should believe in the unicorn, in the defense of the gullible among us, I want to say this. Nature has produced some rather implausible creatures. If you think about a giraffe, with that long neck, or the kangaroos, hopping about with their young in a pouch, they're far less plausible than a unicorn. Why shouldn't one believe in a unicorn?

We asked Janetta to explain the medieval abhorrence of experimentation:

JRB: You did not experiment. The church opposed it. Experimenting was a Renaissance idea to investigate nature contrary to the church. Investigating the human body in the medical profession, again, contrary to the church. In Medieval literature about animals, each was a separate entry. The first part described the animal's physical attributes which included blue animals and things that can't possibly exist in nature. The second part used those characteristics to develop a model, a moral model that you were either to emulate or avoid. Every animal in the Medieval Bestiary was given a religious, symbolic connotation.

EDB: There could be no gray. It was either of God or Satan and nothing in between. Anything venomous would be of the Devil...

JRB: That goes back to Adam and Eve. Dragons and serpents are basically the same creature in literature. They didn't make a distinction.

EDB: And the Madonna Lily, because of its pure whiteness...

JRB: ...is a symbol of purity. The lion could be both.

EDB: One of things I wanted to ask you about was the medieval love of using a symbol that is completely self-contradictory.

JRB: It depends on the context in which it appears. That's the key. Black and white were admired but gray was more desirable. Basically, in the nuanced interpretation, everything should be complex and related to God. And it's a way, I think, of trying to understand a world that you cannot yet understand. The folklore mentality, until the Renaissance, avoids investigation.

EDB: When looking at illuminated manuscripts, do you think that the observer approaches the work more spiritually if it is considered illuminated as opposed to a book from last week that is merely illustrated?

JRB: Yes, I think so. I would expect it to have greater import if I lived during the Middle Ages. I would be looking for guidance. Most people were illiterate including large portions of the clergy. They would have heard the stories and been told the symbols again and again from the pulpit.

EDB: And you walked through the church and all the images were teaching you.

JRB: Yes, the bible carved in stone.

JRB: I wanted to show you this figure... the way the human body is depicted changes, it becomes more realistic. A piece like this... Chartres Cathedral in the west portal has this type of very elongated, column figures. They're referred to as column figures because they're shaped like columns and they function like columns. I like how extremely immaterial he is... his feet don't rest on anything. They simply dangle and there's a multitude of tiny folds, all perfectly carved. Contrary to gravity these folds go up rather than down. The lack of realism is not due to a lack of technical skill. Gradually the human body starts to get bigger, it gets wider, it starts to move in space rather than standing perfectly still. Then the figures start to talk to one another. First two, then four. They really come to life. There's that hip shot pose that takes contrapposto further -- Mary supporting Jesus on her hip.

EDB: Like in Greek sculpture you go from the Kouros figure to the contrapposto to the hip shot, and then then next thing you know...

JRB: You get an A. Absolutely. It's exactly the same development.

EDB: We were wondering, what was your first experience of viscerally reacting to a work of art that made you know that at was going to be your life.

JRB: I would be very hard pressed to pick out a single experience. There are a number of things that I really love. There are artists that I really love. I do have a favorite. A question that I ask every class is, if you could meet any of the artists we studied and language was not a problem, and you could have a meal with them, who would you want? I would pick Leonardo da Vinci because I would want to try to get into that mind although I know now that a lot of the things with which he is credited existed before him. A lot of his ideas were in fact derivative. Still, what a mind. I would like to have some insight into his way of thinking that he could be so adept and so agile in so very many different fields. Today we are expected to specialize whereas the idea of the Renaissance Man, where your mind could go from one thing to another with each one of them benefiting... that's the aspect that appeals to me.

After discussing many other things we enter a gallery containing a wooden sculpture of the Madonna and Child.

JRB: Can I show you a piece that I like? She is a type. This figure is from the twelfth century and could have been made anywhere in Europe that art was produced. Mary is enthroned and Jesus is in her lap. She is stiff and immobile. She does not twist or bend. She is unapproachable and there is that drapery that is contrary to the laws of gravity. And if I can find you one from just a century or so later, she is going to come to life. She's going to stand up and smile. Jesus is going to stop looking like a little old man and will take on the proportions of a baby. He gets younger rather than older and Mary will be holding him on her hip. That's the difference between Romanesque and Gothic and you see it again and again.

EDB: The Egyptian children were never depicted as babies either, they were just miniature adults.

JRB: Tiny adults, scaled down. That one really does have adult proportions. There's a family resemblance between mother and child.

ABD: I think one of the notions that interests us is how much of the Pagan world survived in the medieval world.

JRB: Absolutely. The church encouraged that as a way for people to transition from Paganism to Christianity. It was purposely done. A lot of the stories reappear.

EDB: When you think about the process of the Christianization of Europe, many of the formerly Pagan people were easily able to accept Christianity because there was another guy dead in a tree and they were used to being able to think that way... So this accretion of symbols, layers and layers of images, symbols and meanings... the conglomerate is what Christianity eventually became. I was wondering, in terms of art, how do you like to look at things and peel away the layers and see what comes from the Pagans, what from Christ or this region or that... do you think of it in those terms?

JRB: I wrote my doctoral dissertation on that, actually. I wrote on the upper church of San Francesco. I argued that, if you say that the Renaissance was a rebirth of the antique, how far back could I push it? I took it through a whole series of motifs including figures on the tops of buildings, garlands, the use of linear perspective... all the way back to antiquity. They are motifs that you find in so much art, especially perspective. There was not scientific perspective but approximate perspective which died out in the Middle Ages and I was saying yes, but there were some exceptions. Particularly in the borders of things, the framing, the illusionistic framing of things as in the upper church of San Francesco of Assisi. I argue that it's based on antiquity and if you permit yourself to stand where the lines lead, then you will automatically read them in the right order. My favorite example of the perpetuation of things from antiquity through the Middle Ages is the story of Androcles and the Lion in which Androcles is going to be sacrificed in the arena to the lion and the lion comes out and instead it greets Androcles and licks his hand because years ago he had removed a thorn from its paw and people are so impressed that they free both Androcles and the Lion and then they go around town with the lion on a leash. St. Jerome and the Lion is a reiteration of the same ancient story. It becomes one of this identifying stories.

Our conversation did not end here, it covered enough for another dozen articles. (Stay tuned) When we met the charming, witty, dignified and erudite Janetta, we could not have known that our afternoon with her would be an adventure we will never forget. Since that day, in reading some of her books, we have come to deeply respect the depth and thoroughness of her scholarship while being delighted by her wit. Honestly, we found ourselves laughing out loud on many an occasion. If you go to one of her lectures, you may hear something like this:

JRB: The lectures always end in rhymed couplets. If you wanted to end your article on a light note, you could include one of the rhymes.

Dear Michelangelo I'd just like a peek

At the man who modeled for that fantastic physique

It doesn't take much to figure out

Michelangelo's model for working out

Was the tortuous theme of "no pain, no gain"

Long before Jack Lalanne.

They're intended to let people know when the lecture is over because I've been in lectures where people are left feeling uncomfortable because they just don't know if it's time to stand up to applaud and leave. They're meant to summarize. I want to put the main words back before their eyes before they leave. I want them smiling and I want their endorphins flowing. I want them to feel good.

Janetta left us feeling more than good. You will feel it too if you are lucky enough to attend one of her Art is Alive lectures. If you attend one of the limited availability "Lunch with the Lecturer" events after her lectures you will be luckier still, as you will get a taste of the wonderful experience we had wandering the Metropolitan Museum of Art with the incomparable Dr. Janetta Rebold Benton.