As crime reporters, part of our job is to enter your personal space on the worst day of your life.

It's rarely our intention to upset you further when, say, your family member is the victim or the perpetrator of a crime. On the contrary, we genuinely want to give you an opportunity to give your side of the story. Without the people closest to a story, we only have rumors on Twitter, second-hand witnesses or -- and this is the worst part -- the extremely limited information we get from the cops during a breaking news situation.

There's not much more frustrating than hearing a "no comment, this is an active investigation" from the police. It means that, instead of running primary-source information, we have to knock on every door in the city to find out the who, what, when, where and why ourselves. Meanwhile, plenty of news organizations are perpetuating rumors and misinformation (remember the New York Post's "BAG MEN" cover?), or simply getting their facts wrong.

And when there's a throng of dozens or hundreds of reporters -- all of whom have little or no information from the police -- in a city that has just gone through a life-changing tragedy, people are going to get pissed off. It's completely understandable.

Our police and public officials can help alleviate some of the burden that locals and reporters take on during breaking news situations. All they have to do is follow the lead of the Seattle Police Department. Its public affairs office released so much timely and important facts during the shooting at Seattle Pacific University on Thursday that I thought their Twitter might have been hacked by a crime reporter.

It turns out that one of the guys leading the SPD's social media operation is indeed a former crime reporter. Between Jonah Spangenthal-Lee's first tweet alerting us to the shooting at 3:28 p.m. and his followup tweet naming the shooting suspect at 11:27 p.m., we got something crime reporters rarely get from police organizations during an active crime scene: Information. Lots of information.

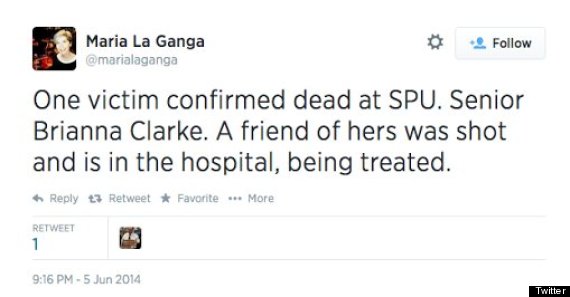

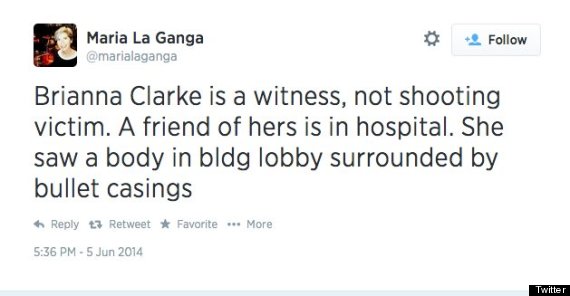

That information meant that public offices' phone lines were freed up from thousands of calls from reporters and locals. It meant that students still stuck inside their buildings felt some sense of security. It meant that misinformation like this was quickly extinguished:

Brianna Clarke wasn't killed, nor were there seven victims like many news outlets first reported. But the SPD had it all under control. L.A. Times reporter Maria La Ganga later retracted her tweet:

The SPD's response was refreshing, and should be followed by police departments across the country.

"From my time as a crime reporter, I knew it was really hard to get info out of the police department," said Spangenthal-Lee, formerly of KIRO television and other Seattle news outlets. "Plus, for the average person who's not paid to chase down leads, it can be really difficult to figure out why there are, say, cop cars down your street. We want a place that people can go to find that information.

"Direct communication with the public, and the news, is important. On Thursday, for instance, we knew that if people are worried there's a second gunman on the loose, we need to address that quickly and accurately. And we did."

In a perfect world, we reporters wouldn't travel in throngs to your doorsteps -- we'd leave our information and speak briefly, and if you want to give us a call, that's up to you. But that's never going to happen, and with new technology comes new ways to contact you and yours.

That said, with new technology comes new opportunities for police to communicate with the public.

When there is an abundance of information at your fingertips, as was the case on Thursday because of the SPD, people feel safer, and the information we publish is accurate. To be sure, we have less of a reason to bug you. Once all the basic information is out there, the pool of people we have to blindly make calls to begins to dry up.

Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook |

Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter |

![]() Contact The Author

Contact The Author