In Stalinist Eastern Europe, political parties were banned and criticism of the regime was dangerous. As in today's North Korea or Assad's Syria, public spaces were controlled, propaganda was all-encompassing and fear was widespread. Yet even in a society gripped by terror, young people found ways to express their discontent, just as they have so recently in the Arab world and North Africa. Like the young women of Pussy Riot in Russia today, they also learned how to use pop culture -- imported from the West -- as a tool of resistance against the communist regimes. This adapted excerpt from Pulitzer-prize winning historian Anne Applebaum's new book, Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944-1956 (Doubleday), explains how such resistance functioned in Eastern Europe, even in the harshest and most oppressive years of communist occupation.

BY THE YEAR 1950 or 1951, it was no longer possible to identify anything so coherent as a political opposition anywhere in Eastern Europe. The public sphere had been cleansed so thoroughly that visitor to Warsaw -- or to Prague, Sofia, Budapest and East Berlin -- in the early 1950s would have observed no dissent whatsoever. The press contained regime propaganda. Holidays were celebrated with regime parades. Conversations did not deviate from the official line if an outsider were present.

And yet -- there was opposition. It was not active, it was not always visible and it was certainly not armed. Some of its members could be found, at other times, mouthing the regime propaganda or marching in the parades. And many of them resented it. They were embarrassed or ashamed by the things they had to do in order to keep their jobs, protect their families and stay out of jail. They were disgusted by the hypocrisy of public life, bored by the peace demonstrations and parades which impressed outsiders. They were stultified by the dull meetings and the empty slogans, uninterested in the leader's speeches and the endless lectures. Unable to do anything about it openly, they got their revenge behind the party's back.

Not by accident, young people were the most enthusiastic of the passive resisters to High Stalinism, if 'enthusiasm' is a word which can be used in this context. They were the focus of the heaviest, most concentrated and most strictly enforced propaganda, which they heard at school and in their youth groups. They bore the brunt of the regime's various campaigns and obsessions, they were sent round to collect the subscription money, gather signatures and organize rallies. At the same time, they were less cowed by the horrors of a war which they didn't necessarily remember, and less intimidated by the prospect of prison which they had yet to experience.

They couldn't join political parties, they could protest and they couldn't speak out. If they even told jokes about their leaders they risked expulsion from school, or even arrest. And so, in the late 1940s -- just as Western teenagers were beginning to discover long hair and blue jeans -- East European teenagers living under Stalinist regimes discovered narrow trousers, shoulder pads, red socks and jazz.

In Poland, these early youth rebels were called bikiniarze, possibly after the Pacific atoll where the United States tested the first atomic bomb -- or, more likely, after the Hawaiian/Pacific/Bikini-themed ties which some of the truly hip bikiniarze managed to obtain from the care packages sent by the United Nations and other relief organizations. Those who were very lucky also got hold of makarturki, sunglasses resembling those worn by General MacArthur. In Hungary, they were called the jampecek, a word which roughly translates as 'spivs'. In Germany -- both East and West -- they were the Halbstarke, or 'half-strong'. There was a Czech version of the youth rebel -- the potapka, or duck, probably named after the ducktail hairstyle. The Romanian youth rebels were known as the malagambisti, named after a famously cool Romanian drummer, Sergiu Malagamba.

The fashions adopted by these youth rebels varied slightly from country to country as well, depending on what was actually available in flea markets and what could be made from scratch. Generally speaking, the boys favoured narrow, drainpipe trousers (in Warsaw there was a tailor who specialized in making them out of ordinary ones). The girls at first wore tight pencil skirts, though later they switched to the 'New Look' then being sold by Christian Dior and copied everywhere else: dresses with small waists and wide skirts, preferably in loud colours and patterns. Both favoured shoes with thick rubber soles -- a distant echo of the American sneaker -- which in Hungary came to be called jampi shoes.

Brightly coloured shirts were popular too, since they contrasted so starkly with the conformist uniforms of the communist youth movements, as were wide ties, often hand-painted. The idea was that shirts and ties should clash. Particularly popular was the combination of a green tie and a yellow shirt, known in Polish as 'chives on scrambled egg'. In Warsaw, the jazz critic Leopold Tyrmand popularized the wearing of striped socks as well. He did so, he once said, to demonstrate 'the right to one's own taste.'

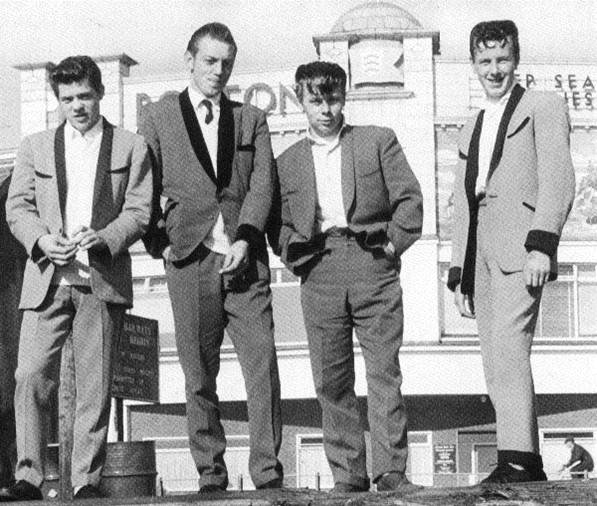

The bikiniarze. Early "Gangham Style"? [Photo courtesy of the author.]

As in the West, the clothes were associated with music. Like their West European counterparts, the bikiniarze, the jampecek and the others started out as jazz fans, despite -- or thanks to -- communist campaigns against jazz: in one famous incident, young communists entered the Warsaw YMCA and smashed up all the jazz records. But once it had been forbidden, jazz music became instantly attractive to anyone who wanted to defy the regime. Even to listen to jazz on the radio became a political activity: to twiddle the dials of one's father's radio in an attempt to catch different stations through the static became a form of surrogate dissent.

Radio Luxemburg was weirdly popular, as were the jazz programmes on Voice of America later on. This would remain a dissident activity until the communist regimes collapsed 40 years later. The clothes were also associated with a certain set of desires and a way of life. Like Western teenagers, the binkiniarze and the Malagambisti wanted possessions. In particular, they wanted possessions which the communist system could not provide, and they went out of their way to get them. One former Hungarian jampecek remembered the lengths to which he went to get hold of the thick-soled shoes:

There were dealers in the southern district, three of them. I don't know their names, Frici somebody-or-other, they brought the stuff in. I think from Yugoslavia or the South ... It was a big thing that you could buy it on the side, in installments. You had to have connections to get hold of it ... People envied each other for where they'd bought stuff ...

The regime soon suspected that admiration for Western fashions implied an admiration for Western politics too. Very quickly, the press began to accuse the youth rebels not just of non-conformism, but of propagating degenerate American culture, of plotting to undermine communist values, even of taking orders from the West.

One Polish newspaper described American pop culture as "a cult of fame and luxury, the acceptance and glorification of the most primitive desires, the filling of a hunger for sensation." Another equated the bikniarze with "speculators, kulaks, hooligans and reactionaries."

At times the youth rebels were called saboteurs, or even spies. Perversely, this kind of propaganda had the effect of making these inchoate groups seem, and eventually become, more powerful and more important. Some have even wondered whether the youth subculture was perhaps created by the newspaper propaganda. Communist authorities, needing something against which to define themselves, may have helped invent them, deriving their description from the "Westerns, gangster films, dime novels and comic books" which made their way across the Western borders. This language in turn actually drew young people to jazz, to "Western" dancing and to more exotic forms of dress.

But once they had been defined as outlaws, these fashionable groups began to attract people who really were looking for a fight. In Poland, there were frequent, serious squabbles between bikiniarze and zetempowcy (a nickname derived from the Polish acronym of the Union of Polish Youth, ZMP), as well as between the bikiniarze and the police. In 1951, a group of young people from a Warsaw suburb went on trial for alleged armed robbery. Sztandar Młodych, the official youth newspaper, described them as "young bandits serving American imperialism," and claimed they had been dressed in the characteristic narrow trousers and thick-soled shoes. One young communist activist wrote in to Sztandar Młodych to complain that he too had been convinced that "admirers of the American life style are hostile to People's Poland" after having been beaten up by a group of young "hooligans" dressed as bikiniarze. He had been wearing his red Union of Polish Youth tie.

The reverse was also true. Young communists, sometimes in tandem with the police, hunted bikiniarze in the streets: they would catch them, beat them up, cut their hair and slash their ties. More than one "official" youth dance party was ruined when bikiniarze began to dance "in the style" -- meaning the jitterbug -- after which they were beaten up by their "offended" peers. "Whenever bikiniarze jumped on to the dance floor, the young communists hauled them off and beat them up," one communist youth official remembered.

In East Germany, the youth "problem" was made more acute by the undeniable influence of American radio, which was available not just on crackly, distant Radio Luxemburg also on RIAS, "Radio in the American Sector," broadcast directly from West Berlin. West German sheet music was also available for East German dance bands, and to the great consternation of the regime it was extremely popular. At a German composers' conference in 1951, an East German musicologist denounced this sheet music as "American entertainment kitsch" as a "channel through which the poison of Americanism penetrates and threatens to anaesthetize the minds of workers." The threat from jazz, swing and big band music was, he said,"just as dangerous as a military attack with poison gases." After all, it reflected: "the degenerate ideology of American monopoly capital with its lack of culture ... its empty sensationalism and above all its fury for war and destruction ... We should speak plainly here of a fifth column of Americanism. It would be wrong to misjudge the dangerous role of American hit music in the preparation for war."

The East German state began to take active measures to fight against this new scourge. Around the country, regional governments began to force dance bands and musicians to obtain licences. Some banned jazz outright. Though the enforcement was irregular, there were arrests. The writer Eric Loest remembered one jazz musician who, when told to change his music selection, pointed out that he was playing the music of the oppressed Negro minority. He was arrested anyway, and went to prison for two years.

The regime also sought alternative, but this wasn't easy: After all, nobody was quite sure what progressive dance music was supposed to sound like, or where it was supposed to be played. At the Germany Academy of Art, a learned commission of musicologists came together to discuss the "role of dance music in our society." They agreed that "dance music must be purposeful music," which meant it should be only for dancing. But those present could not agree on whether dance music should be played on the radio -- "merely listening to dance music is impossible, the listener will forget what its purpose was supposed to be" -- and they feared young people would ask for "boogie-woogie" instead of "real" dance music anyway.

In May 1952, the Culture Ministry tried to solve the problem with a competition and prizes to be given to composers of "new German dance music." The competition failed, as none of the entries were deemed sufficiently progressive. As the new "Dance Commission" of the Central Committee complained, much of the work submitted was based on unprogressive, uneducational themes such as sentimental love, nostalgia or pure escapism. One song about Hawaii, the committee declared, could just as well be set in Lübeck.

Most of the time, young East Germans responded to this sort of thing with howls of laughter. Some bands openly mocked letters they had received from party officials and read them aloud to audiences. Others simply flouted the rules. One shocked official wrote a report describing the "wild cascades of sound at high volume" and the "wild bodily dislocations" he'd heard at one concert. Inevitably, there were escapes as well. One band, dismissed by the authorities as a "propagandist for American unculture" caused a sensation by fleeing to the West and then immediately beaming its music back into East Berlin on RIAS.

In the end, the authorities never did find a solution to the "problems" of Western music and youth fashion, not in the 1950s and not later. If anything, both became even more alluring after the first, sensational recording of "Rock Around the Clock" reached the East in 1956, heralding the arrival of rock and roll. But by that time, the communist regimes had stopped fighting. The battle against Western pop culture was fought and lost in East Germany even before the Berlin Wall was built -- and everywhere else, too.