Before you begin reading, please listen to this link of Bob Dylan's Theme Time Radio Hour, Episode 35, "Women's Names." It's Dylan reading Edgar Allan Poe's last poem, "Annabel Lee," to the appropriate accompaniment of seagulls and the sound of waves in the background.

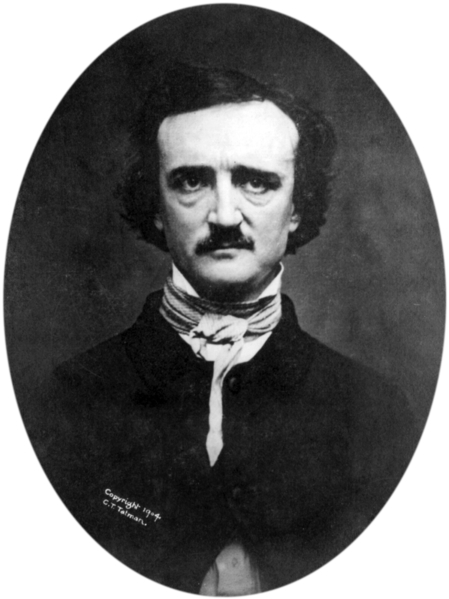

Would you like to understand Bob Dylan? Get in line -- folks have been wanting this for the past half century and good luck. You can, however, understand, and appreciate more through his view of them, some of the writers who've had an influence on Dylan as an artist. Edgar Allan Poe, the fender-bender poet -- whether or not you're capitalizing the F of fender, it works -- is a writer who matters to Dylan, and has for a long time.

I'm not the first person to have seen Dylan's links to Poe. As is often the case with Dylan, he noted it himself first. In the first volume, so far, of his autobiography, Chronicles: Volume 1, Dylan remembers a song he wrote (but hasn't released, yet) sometime in the early 1960s, as a young man in New York. "I memorized Poe's "The Bells" and strummed it to a melody on my guitar." Dylan has said that two sounds comfort him: trains and bells. His songs ring with bells -- "Ring them Bells," "Chimes of Freedom," Methodist bells, the undertaker's bell, mission bells, pointed shoes and bells. Once upon a time, Dylan considered following in some of Poe's footsteps less trodden -- " I had even wanted to go to West Point."

Working on his first novel -- so far -- in the mid-1960s, now famous and grappling painfully with that fame, Dylan turned to Poe for inspiration, and perhaps for comfort: the last section of Tarantula is called "Al Aaraaf and The Forcing Committee." It might be a gold-bug of fortune and fame, it might be a tarantula, whatever bites you. It's worth mentioning that Captain Kidd appears in Tarantula too, as well as in "Bob Dylan's 115th Dream" and in Chronicles, where he recalls hunting for Kidd's treasure in the Hamptons with his children. Of his crazy, maddening fame by the time he was writing Tarantula, in 1966, Dylan said simply, years later, "It was like being in an Edgar Allan Poe story."

When he turned to moviemaking, Dylan thought of Poe. Ron Rosenbaum wrote about, among other things, the filming of Dylan's Renaldo and Clara in 1978. An intense scene from the movie shaped itself like this: "Onscreen, Renaldo, played by Bob Dylan, and Clara, played by Sara Dylan (the movie was shot before the divorce -- though not long before), are interrupted in the midst of connubial foolery by a knock at the door. In walks Joan Baez [Dylan's former girlfriend], dressed in white from head to toe, carrying a red rose. She says she's come for Renaldo. When Dylan, as Renaldo, sees who it is, his jaw drops. At the dubbing console, one of the sound men stopped the film at the jaw-drop frame and asked, 'You want me to get rid of that footstep noise in the background, Bob?' 'What footstep noise?' Dylan asked. 'When Joan comes in and we go to Renaldo, there's some hind of footstep noise in the background, maybe from outside the door.' 'Those aren't footsteps,' said Dylan. 'That's the beating of Renaldo's heart.' 'What makes you so sure?' the sound man asked teasingly. 'I know him pretty well,' Dylan said, 'I know him by heart.' 'You want it kept there, then?' 'I want it louder,' Dylan said. He turned to me. 'You ever read that thing by Poe, "The Tell-Tale Heart"?"

Poe is in Dylan's song lyrics, too, and of all the writers Dylan's used in his work, all the influences lurking there, Poe (along with Williams Shakespeare and Blake) is one of the most long-lived and consistent. The references Dylan makes to Poe don't take an eagle eye to find -- they're in very plain view. "My love she's like some raven /At my window with a broken wing," ("Love Minus Zero/No Limit," 1965); "Don't put on any airs when you're down on Rue Morgue Avenue" ("Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues," also 1965). And much more recently, Poe remains: on "Tempest," Dylan's 35th and most recent studio album, released last year, you can hear him sing about a train whistle "blowing like she's at my chamber door" -- an oncoming train, scarier than a raven? Maybe. Maybe not. But Jerome McGann's reading of "The Bells" inspired me to notice that Dylan's song, "Duquesne Whistle," scans in near-perfect trochaic pentameter.

In "Tempest's" title track, a ballad about the sinking of the RMS Titanic, a poem Poe labored over, "The City in the Sea," offers up some most appropriate lines: "Lo! Death has reared himself a throne / In a strange city lying alone, / Far down within the dim West, / Where the good and the bad and the worst and the best / Have gone to their eternal rest." Dylan sings, rather more gently: "When the Reaper's task had ended / Sixteen hundred of the best / The good, the bad, the rich, the poor / The loveliest and the best."

Dylan's not unique among musicians in his admiration for Poe. Those popularly regarded as the bardic poets among singer/ songwriters are drawn to Poe, with quite varying degrees of aptitude and success. Witness Lou Reed's "The Raven" concept album of 2003. Anne Decatur Danielewski renamed herself Poe in the mid-90s and her one hit record, so far, is called Haunted. Antony & the Johnsons have a spoken-word recording of "The Lake" set largely to an unrelenting, lake-water-lapping piano. Beautiful, tragic Jeff Buckley has a fabulous reading, to twangy guitar, of "Ulalume."

People close to Dylan, and musicians and performers whose style he's said he admires, have recorded Poe. Joan Baez sang "Annabel Lee" in 1967, on her album Joan. It starts with a rather flatulent inappropriate instrumental line, thanks to Peter Shickele, and then drifts away into Joan's ethereal soprano which is rather spoiled by a tinkly background. Her delivery of the lyric is beautiful, though, in that voice which, as Dylan once said, "drove out bad spirits." Dylan's friend Phil Ochs recorded a version of "The Bells." And Lord Buckley released his beat version of "the swinging Edgar Allan Poe's" magnificent poem "The Raven" in 1969. At midnight, "I was goofing (beat) and weary, when suddenly there came a tapping, as if some cat were gently riffing, knocking rhythm at my pad's door. 'Ah, tis the landlady,' I muttered, 'on her broom she flies...." Buckley's is a singular and spectacular tribute to "that sweet square but swinging maiden whom the fly chicks tag Lenore, nameless here forevermore."

Christopher Rollaston, Michael Gray, Harold Lepidus, Scott Warmuth, and other writers on Dylan have picked up on some of these moments, and written about Dylan's mentions of Poe. Scholars and Dylanologists have also written about Shakespeare, Ovid, William Blake, James Joyce, and a slew of 19th-century Americans: Poe, John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Timrod, Walt Whitman. They're all in Dylan, too. Whittier he uses frequently on "Tempest," which would surely annoy Poe, no Whittier fan. Writing of the poet, Poe used his autograph for a sly entre into critique: "J. GREENLEAF WHITTIER is placed by his particular admirers in the very front rank of American poets. We are not disposed, however, to agree with their decision in every respect. Mr. Whittier is a fine versifier, so far as strength is regarded independently of modulation. His subjects, too, are usually chosen with the view of affording scope to a certain vivida vis of expression which seems to be his forte; but in taste, and especially in imagination, which Coleridge has justly styled the soul of all poetry, he is ever remarkably deficient. His themes are never to our liking. His chirography is an ordinary clerk's hand, affording little indication of character."

Now when it comes to Poe, I can't go nearly as far as does Rollaston, who finds that Dylan's mentions "impl[y] Poe as an alter ego for Dylan" -- or, as Rollaston puts it more intensely, there is "much Poe blood on Dylan's tracks." If Dylan has such a thing as a literary alter ego, and I don't believe he does, it's Shakespeare. Or Blake, perhaps a better choice, since Dylan is a painter, too. That Poe and Dylan are both American, and globally popular, is hardly enough. After all, Dylan gets his blood, his macabre -- as I'd say Poe did, too -- from two places: from Shakespeare, and from his own imagination.

[To be continued in a second part.]