At 7 p.m. on the day the storm hit, 65-year-old Ronnie Landfield climbed down the ladder to the basement of his building on Desbrosses street, one block away from the Hudson River in downtown Manhattan. It was bone-dry. Half an hour later, he peered through his first floor apartment window and saw a raging river in the street.

As three feet of water surged into his ground floor studio, Landfield's hope and confusion were replaced by fear and dread. Scores of large paintings, spanning 50 years of work, were being swathed in grimy river floodwater. Landfield and his wife, trapped upstairs, could only sit and wait anxiously for the 10,000-mile-wide ferocity to pass.

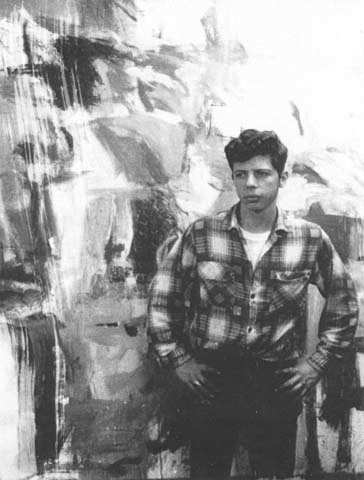

Landfield was born (1947) and raised in the Bronx. His mother was a bookkeeper; his father drove a truck. Today Landfield is widely regarded as "one of the best painters in America." By the time he was 13, he was living, eating and breathing art.

Growing up in New York in the 1960s -- a buzzing landmark period in the New York art world -- he was immediately inspired by Pollock, de Kooning , Franz Kline and abstract expressionism. He began churning out large sophisticated paintings, and by the time he reached 20 years of age he was showing his work at the Whitney Annual (which is now the Whitney Biennal) and had his first solo show at the David Whitney gallery. Over the five decades that followed, he had a further 60 solo shows across the world. His work is included in major institutions such as the MoMa, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum, among others.

Ronnie Landfield, age 16.

Last Thursday, I met him in his home on Desbrosses street, where he has been residing since 1969. I had spent "New York's longest week" totally unaffected in Brooklyn, so the reality of Landfield's situation cut into me like a knife.

Even though the nor'easter that blasted through New York the night before had pushed temperatures down to the low 40s, it was actually colder inside Landfield's building than out. With the electricity still out of action (this was day 11) the place was pitch-dark (I had to feel my way along the walls to make it up the stairs), and it had that kind of freezing wet-cold that you can feel seeping into your clothes, making them heavy.

Through the haze I saw the weary ashen faces, of Landfield, his wife, Jenny, and his son, Noah, trying to keep warm under thick wooly hats and, by now, soiled work clothes. In the living quarters upstairs, a couple of small candles flickered in the cramped kitchen area and the adjoining space was cluttered with household items, books and stacks of papers.

Some weak rays filtered through the tiny windows down in the studio, which was a chaotic disarray of paint-pots, artworks that had been shifted by the surge, and putrid soaking-wet paintings lying rolled up on the floor.

The place was like a scene from Cormac McCarthy's The Road. Except that, leaning haphazardly against one another, around all four walls, the enormous 10- to 12-foot tall paintings adorned with the warm, vibrant, expansive and idyllic fields of color that Landfield is famous for -- muted now due to the lack of light -- afforded a peculiar irony.

As I took all this in, I remembered critic Eleanor Heart's appraisal: "Generally the light in these paintings seems to come from behind the colors, glowing through with flame-like intensity... Landfield is all light-filled joy."

Post-Sandy, the big dilemma was -- and continues to be -- how to save Landfield's oeuvre from mold and rot. More than 300 enormous paintings, including the countless drawings and paintings on paper that date back to 1960s, need to be moved to a dry cool space. But, neither transport nor a space has been available to him.

Noah, 33, also an artist, is cool, calm and collected. Softly spoken and sweet, he has taken control of situation and is managing everything.

Moving his father's works to his studio in Sunset Park, unfortunately, isn't an option since that building was also damaged by the storm, and the elevator isn't working.

"How are you today?" I ask Landfield. He looks at me, and is a little tongue-tied. He is drained and hardly even knows how he feels at this point, but he tells me he's alright, and says something to the effect of "onwards and upwards."

Ronnie Landfield in his studio, November 8 2012

In truth, Landfield is stuggling to withstand the emotional trauma, the stress and the consequent fatigue. His back is "killing him."

A few moments later, looking around the room, he says, "I think I won't be painting for a while."

Landfield and I go upstairs, leaving Noah to press on for the umpteenth hour with cutting the wooden frames off the canvases and spraying them with Lysol and alcohol to fight the mold.

On the way up, Landfield tells me that two blocks away a guy who was in a parking lot drowned. It came on so fast that he got trapped. "So in a way we're all lucky..."

In what I'm guessing is usually the dining room, he points to large pile of soggy works on paper that are slumped in the middle of the room.

"These are ones I did when I was 16. In 1963..." He digs out a wrinkled figure painting, Nude In Orange.

This is his cue to launch into his biography, which he reels off as if on auto-pilot (understandably he gets asked tell it often). It is peppered with the names of all the legendary artists and art world kingpins in New York at that time.

The Deluge, 1999

From age 13, every afternoon he would gather with his High School of Art and Design friends and walk up two blocks to 57th street to the Sidney Janis gallery (the "Ground Zero" of the New York art world at that time, which handled all the major abstract expressionists: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, etc.) and all the other "big" contemporary galleries along 57th street. When New Realism -- later characterized as Pop Art -- stormed onto the scene, enraging the abstract expressionists and pushing them out. Young Landfield was right there watching. It was in this lively milieu, he tells me, that he gained his "world-class education."

He reveals, as evidenced in a string of episodes, that he was ambitious, bold and a little cocky.

"I was more than a rebel, I was rebellious." He still has a touch of tough-guy bravado in his voice.

Some of this comes from his experiences at the High School of Art and Design, his first art school. At 13, going into 10th grade, he was the youngest of the kids. He didn't think he had any talent. The other students used to laugh at his work and he became "the class clown." So, he had to steel himself against them. As a result, he developed a strong sense of self-belief, of not caring what people might think -- undoubtedly one of the main reasons he achieved such success as an artist.

Across The Darkness, 2010

"[At the end of he 60s,] Donald Judd and everyone were saying that 'painting is dead.' I was 20 years old and I wanted to paint."

Not only did Landfield not accept this, he reacted against it somewhat, through making very loose and free painterly works. "I thought, 'Who are they to tell me I can't be expressionistic? Who are they to tell me I can't use imagery or paint landscape?' I don't care if it's 'old fashioned.'"

Landfield put the hard edge borders in, as well as soft ones. He was breaking as many rules as he could, and started to develop his own vision.

It just so happens that the High School of Art and Design are currently holding an exhibition of his work. His life-story has come full circle, as it were. Where It All Began features seven recent paintings, selected by Landfield, to commemorate the opening of the school's new site on East 56th Street.

When the school asked him if he would have this show, Landfield wasn't enthusiastic. It would be a modest setting for an artist such as Landfield whose work hangs in the most prestigious museums and galleries in the world. But he quickly came to his senses, and decided that it would be a great honor. Ironically, it is thanks to this show that seven of his best recent paintings are safe and dry.

Where It All Began exhibition, installation shot. Photo courtesy of Jeffrey Collins and Ed Baynard.

The other almost poetic synchronicity, is that now, because of the heartbreaking blow caused by Sandy, Landfield, as he digs out all of these artworks that he made as a kid, trying desperately to save them, is reflecting on his oeuvre, his career and where it all began.

The paintings in the show are beautiful and bold compositions; the colors are dense fiery and vibrant, or soft, transparent and cool. They demonstrate that Landfield, who has now been painting feverishly for over 50 years, continues to work with astonishing talent, passion and energy.

"I just hope all the work in my studio survives this monstrosity. There's no guarantee that it won't all turn to mold and rot. It's just incredibly traumatic."

Photos courtesy of the artist, unless otherwise indicated.