John Elderfield, former chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at MoMA, in front of Willem de Kooning's Park Rosenberg (1957), courtesy of the Willem de Kooning Foundation. Photograph by Jill Krementz.

John Elderfield, former chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at MoMA, in front of Willem de Kooning's Park Rosenberg (1957), courtesy of the Willem de Kooning Foundation. Photograph by Jill Krementz.

When John Elderfield organized a major retrospective of Willem de Kooning's work at New York's Museum of Modern art in 2011, The New York Times' praised it as "exhaustingly large" and "predictably awe-inspiring," noting that one of its greatest strengths was "let(ting) de Kooning be complicated."

Indeed, de Kooning's work has always resisted easy interpretation. His impasto paintings of the 1950s, with their jagged lines and slathered, scraped surfaces, put him at the forefront of the global art scene, alongside other New York Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. But as soon as he mastered one style, he changed it. When he fled New York in 1963 for East Hampton, a small Long Island coastal town, his work began acquiring a curvier, more decisive line. By the 1980s his work was lean, minimal, pared down to the barest essentials of line and color.

Meanwhile, De Kooning was constantly scribbling -- sometimes even with his eyes closed -- revealing a mind that constantly sought new ways of reimagining familiar subjects. Like many artists, he often traded drawings for services. It was from his friend and therapist, Dr. Henry Vogel, that Christie's recently acquired 33 works on paper, going to an online only auction from June 5-19.

Christie's interviewed three people ahead of the auction, each with his own, unique insights into de Kooning and his work. For this first installment, Christie's asked Elderfield, now with Gagosian Gallery, to explain what he sees in the drawings, including de Kooning's long, tumultuous obsession with the female form.

AC: Some of these pieces start at just a few thousand dollars. It's a chance for people to own something by de Kooning who might otherwise never have expected to. What are we seeing here?

JA: There's an old tradition of artists trading drawing with people who provided different kinds of help for them. I'm told that he also traded drawings with his dentist!

There really is a difference between the kind of things that he would make in the 50s and then the [drawings he made in the] 60s and 70s, which are far looser, far more improvisatory. There always was this enormous element of improvisation in de Kooning -- he never really wanted to quite know where he was going, because that gave him the freedom to invent.

Do any of these look to you like they were made with his eyes closed?

It's very possible. It's clear that de Kooning, in his peak, drew all the time. He was right-handed, and he drew with his left hand as well as his right. He drew with both hands together. He drew when he was watching TV. He drew when he was eating meals -- just all the time.

I think because he was so massively productive he just drew and dropped things on the floor and just kept going.

What else do you see?

There's other ones, charcoal ones, where there are a couple of curving lines meandering down the sheet and then a few cross pieces over them and you think, "well, what, actually, is that?" But with de Kooning, there always is something. He is either looking at something or thinking of looking at something when he's making these drawings.

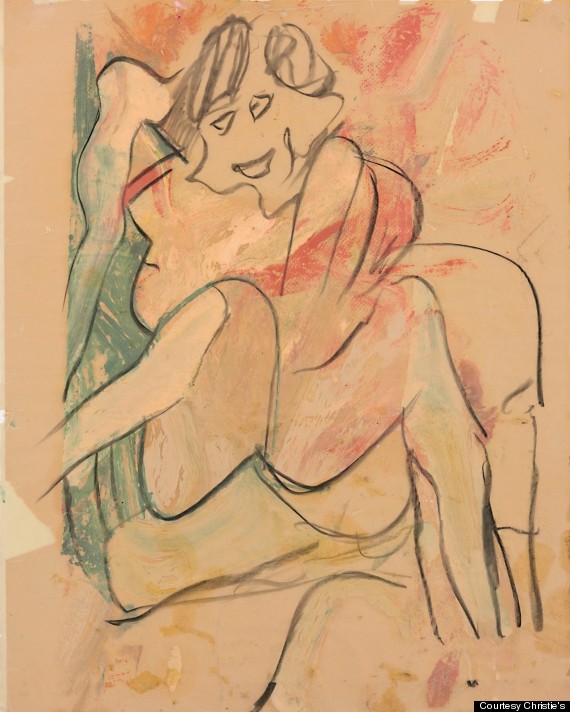

The one that I find actually a bit puzzling is the one with watercolor on -- the sort of sitting woman with her legs open and tinted in the areas. It's very un-de Kooning-like to tint it like that. Because usually his use of color isn't confined by boundaries, it would just move around the sheet.

Willem de Kooning, Untitled (circa 1960s), charcoal and oil on vellum mounted to Kraft paper

Willem de Kooning, Untitled (circa 1960s), charcoal and oil on vellum mounted to Kraft paper

Do you have the sense that de Kooning was beginning to feel stifled by the city? Are we seeing a new freedom the work he made after moving to East Hampton?

Obviously the change that happens after he moves from New York is a big one, initially in painting. Because while the paintings of the early 60s are, if anything, even more abstract than the ones he'd been doing in New York, the color becomes actually more naturalistic. By the mid-60s, he's back to painting a series of women again and, really, from that point onwards, there's always a strong figurative element. Even in the paintings from the mid-70s and 80s that look extraordinarily abstract are, nonetheless, all begun with the figurative drawing. So the whole drawing business was very, very important to him.

Looking at the drawings and paintings from that period, they're lighter and thinner. It seems like there's something going on in terms of the way he makes his line. It seems more decisive, quicker.

I think up through the "Women" paintings of the 50s, his was a massively revisionary process. He would put marks on, he would change them. And everything's a bit tighter. It loosens up with some of the women paintings, and then by the later 50s, he's painting more with his arm than with his wrist and there are these big gestures. I think in the 60s and 70s, he is trying for that kind of fluidity in drawing with his wrist as well, so that, with these works, you have the sense that the arm is moving as well as the wrist, with even the small ones.

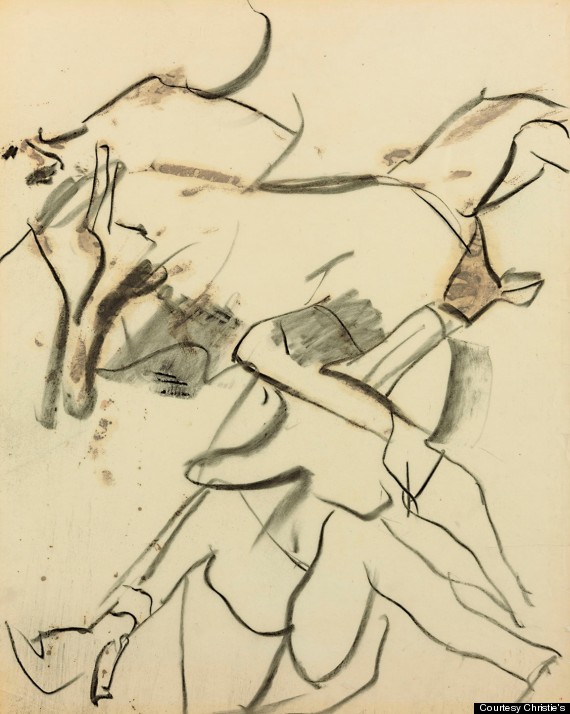

In this group, there's some dense stuff going on. There's one where there's obviously at the bottom of it a splayed-leg woman where you actually see very clearly the high-heeled shoe. And then further up, you can't quite figure out what's going on except that it looks like some kind of limbs and things, and you think, "Oh, it could actually be a horse." You can't tell. Part of the pleasure of this is actually not knowing what they are. They're not firmly fixed. But you sort of know that they've come from some kind of observational memory of looking at things.

Willem de Kooning, Untitled (circa 1960s), charcoal on tracing paper

Willem de Kooning, Untitled (circa 1960s), charcoal on tracing paper

The practice for him as an artist was to make lots and lots of drawings. And it sort of fueled his creativity as well as being a record of his creativity.

There's one of these women who seems to be holding a large fork. It's on one of the lined sheets. What is that thing? Is she digging in the garden? Or is she a devil with a fork?

Or is she ready to eat de Kooning for breakfast?

Yeah, I mean there's one of them where it's definitely some kind of strange beast. It's the one which is dedicated "To Henry, from Bill."