Lorraine Gordon is twelve years older than The Village Vanguard, which this past week celebrated its 80th birthday. Lorraine -- who has owned the Vanguard since her husband, Max Gordon, passed in 1989 -- is, at 92, an inescapably frailer version of what she has always been: indomitable. This means that, as she makes her way on her own over to the Vanguard on Seventh Avenue South from her apartment near Sixth Avenue on the Soho/Greenwich Village border, Lorraine walks much more slowly and carefully. Two hands on the railing is a must, going down the steep Vanguard stairway that she once descended in a rush. Lorraine's daughter, Deborah, pretty much runs the place now, alongside Jed Eisenman, Lorraine's longtime right-hand man. Lorraine no longer takes phone reservations in longhand on a yellow pad back in the Vanguard kitchen. She does still holler bathroom directions at discombobulated patrons from her sentry-like spot at a small two-top table near the front door, but she no longer jumps up to escort these lost souls to the loo personally... very much. She will lunge at anyone who pierces the Vanguard veil of silence mid-set with the beam or sound from a cellphone, but she isn't as quick as she used to be.

Lorraine and I together wrote a book a few years ago, Alive at the Village Vanguard, that constituted Lorraine's autobiography, subtitled, "My Life in and Out of Jazz Time." Last week, we decided to mark the latest milestone in what is now nearly a century of milestones for both Lorraine and the Vanguard, by savoring a leisurely dinner in the neighborhood, followed by yet another night at the club, where a series of truly unique and terrifically commemorative performances was going on.

I took her to Bobo, a restaurant I'd been introduced to by a friend not long ago, on our way to a Joshua Redman show at the Vanguard. Bobo occupies an old townhouse at the junction of Seventh Avenue South and West 10th Street. Lorraine and I emerged from our cab into building construction carnage; the roadway beneath our feet torn up and covered with plywood; a dinosaur-sized yellow steamshovel parked in our path; a cavernous construction pit yawning before us. Lorraine howled obscenities at the top of her lungs as I tried to steer her safe passage, decrying the demolition of the Village she has long loved. I couldn't argue with her.

Bobo turned out to be a nice choice, despite the stairs down to its below-grade front door and the ensuing two, long, perilous flights up to a garden terrace dining space I'd not seen on my previous visit. We both ascended gasping for breath, then found ourselves gaping at the sheer loveliness of the setting, with the darkening sky visible through the glass enclosed roof, electric lanterns lighting all around us, and not another diner yet in sight. "Close all the doors!" Lorraine growled to the young server on duty, as he and I helped lower her into a corner seat against the wall. "Don't let anyone else in."

We ordered vodka martinis and oysters; Lorraine's starters of choice. "Too damn expensive," insisted Lorraine, when she saw the menu price for the oysters. Our server informed us that oysters were a dollar-a-piece downstairs at the bar for Happy Hour. Lorraine just eyed the stairs and laughed murderously.

"Honey, you wouldn't believe how beautiful it was last night at the club," she effused, as we scarfed and sipped. "Six piano players. All of them so beautiful."

I knew that Deborah and Lorraine, who normally book every act, had turned the 80th Anniversary programming over to the young pianist, composer and jazz educator Jason Moran, whose theatrical flair we all admired. Moran had put together six different evenings, each focused on a different nugget of Village Vanguard history. The previous, opening night, had been about the piano. Pianists long associated with the Vanguard -- Kenny Barron, Stanley Cowell, Fred Hersch, Ethan Iverson and Jason Moran himself -- had played tribute to the club's rich history of solo piano virtuosos.

"One of the guys played boogie-woogie just for me, because I love it," Lorraine beamed.

"Which one?" I asked.

"I don't remember," Lorraine said.

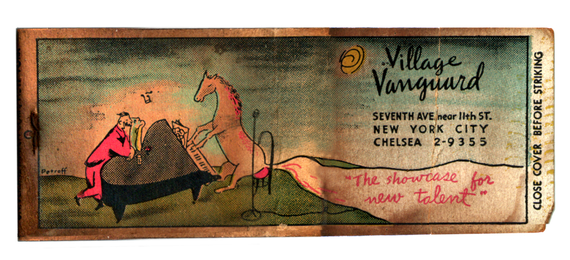

Max Gordon opened the Village Vanguard in February 1935 in a space on Charles Street, before moving it in December of that year into a former basement speakeasy around the corner at 178 Seventh Avenue South, where it has remained ever since. Initially, there was no music at the Village Vanguard. The place was a haven for poets, who rose and recited their work tableside. As Lorraine remarked in Alive at the Village Vanguard, "People threw money on the floor -- that's how the poets got paid."

Tonight, Jason Moran was paying tribute to those early poets with a program featuring his trio, The Bandwagon, backing a pair of very distinguished contemporary poets, the wondrous Elizabeth Alexander -- who notably read at President Obama's first inauguration her poem, "Praise Song for the Day" -- and Yusef Komunyakaa, the 1994 recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

There was absolutely nothing self-consciously literary about what followed, which made it improvisationally combustible in the best Vanguard tradition. The poets alternated, while the musicians offered up ever-shifting rhythmic grooves behind them. Snatches of familiar jazz forms and melodic echoes floated to the surface and submerged again, evocations of Monk and Mingus, Coltrane and Miles, Bill Evans and others too evanescent to identify. Elizabeth Alexander read in a voice bright and clear as sunlight, while Yusef Komunyakaa murmured low. Energies collided and simmered and cooked. Alexander's themes were more personal and self-revealing; Komunyakaa's more oracular.

I couldn't remember having heard anything like it before at the Vanguard, though I know that Lorraine has. I turned to her at the end, in the eruption of applause, and found her fiddling with her hearing aids, her face flushed with pleasure. "I didn't get it all," she crowed, "but it felt wonderful!"

As I write this, the sum of Jason Moran's commemorative vision for the Vanguard is playing out nightly. By the time you read this, it will all be over; the evening of stand-up comedians saluting (with Moran and The Bandwagon) an era of stand-up comedy at the Vanguard that spanned the fifties and early sixties, when Lenny Bruce and Woody Allen both were featured regulars; an evening of Thelonious Monk exclusively, whose music Lorraine and her first husband, Alfred Lion, the founder of Blue Note Records, recorded before anyone else, and whose genius Lorraine preached to the jazz world and beyond with a fervor that finally secured Monk his first gig at the Village Vanguard in 1948; an evening with guitarist Bill Frisell, one of Lorraine's favorite living musicians; and a closing night with the saxophonist Charles Lloyd, triumphantly returning to the Vanguard after a long, long time away.

I could not catch all of these performances. I simply can't live at the Vanguard -- as Lorraine has, and will continue to do so, hopefully, for some time to come. I envy her that.