The horrific suicide bombing at a park in Lahore on Sunday that killed over 70 people, mostly women and children, is one of many assaults by religious hardliners in Pakistan who are striving to remain politically relevant and in the media limelight.

Attacks on soft targets like parks on holidays or schools (the Dec. 16, 2014 attack at the school in Peshawar that killed over 140 children, for example) are the most desperate, sensationalist optics of a multi-pronged strategy with a savvy media component. The aim: to grab political power and impose a harsh version of Islam on a country founded in the name of the religion.

It is no coincidence that the Lahore attack took place on Easter Sunday and targeted Christians. Attacks on other religious communities such as Shiites or Ahmadis -- and there have been many -- just don't grab world headlines in the same way.

The tragedy overshadowed a "religious" -- in quotes because their real agenda is political -- gathering in Islamabad to observe Mumtaz Qadri's chehlum, a prayer for departed souls held 40 days after death. Sunday marked 27 days, not 40, since Qadri's execution. The timing and venue, Pakistan's Parliament, indicate a political motivation.

On official duty as a bodyguard, Qadri shot dead Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer on Jan. 4, 2011; he was inspired by the "religious" rhetoric against Taseer, who had supported Aasia Bibi, a Christian woman sentenced to death in 2010 for alleged blasphemy.

In Qadri, the religious right -- including the well-organized lawyers' consortium behind most blasphemy accusations in Pakistan -- have found a potent, emotive weapon that bridges sectarian divides. Muslims of one sect targeting another sect of Muslims form about half the nearly 4,000 cases filed under the blasphemy laws since 1986. When investigated, such cases are often found to be based in some enmity, rivalry or jealousy.

Qadri belonged to the Barelvi sect of Sunni Islam, a generally peaceful branch of Islam compared to the hardline Wahhabis and Deobandi. Holding up this son of a vegetable seller as warrior of Islam, the Barelvis can assert themselves.

Since the 1980s, patronized by the security establishment, the religious right has gained political ground. Pakistan, along with the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, nurtured the mujahideen to fight in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union. After the Cold War, these religiously motivated fighters provided Pakistan with plausible deniability in the disputed territory of Kashmir and with strategic depth in Afghanistan.

These policies led to the rise of an extreme interpretation of Islam, including Takfiri ideology -- apostatizing other Muslims. Morphing from the mujahideen, the Taliban stepped into the vacuum created after America's departure from Afghanistan and imposed a rigid version of Islam similar to Saudi Arabia's.

The Taliban, al Qaeda and other similar groups oppose Saudi Arabia as a monarchy friendly with the West, even though their rigid ideology originates from Saudi Arabia. This also goes for the death cult -- the so-called Islamic State -- that also has support in Pakistan.

Their goal is to grab political power and impose a harsh version of Islam on a country founded in the name of the religion.

Pakistan's security establishment distanced itself from extremist groups after 9/11 but has been slow to move against its erstwhile "strategic assets." A terrorist attack on Karachi's international airport in 2014 finally catalyzed the military operation in North Waziristan that borders Afghanistan. The lack of transparency remains troubling.

So does the security establishment's continued obliviousness to the anti-India, homegrown jihadis ensconced in Punjab. Since these groups were not attacking Pakistan, the army didn't want to open more fronts.

This changed after the Lahore attack, according to an army spokesman. Several "suspected terrorists and facilitators have been arrested" in raids in cities across Punjab.

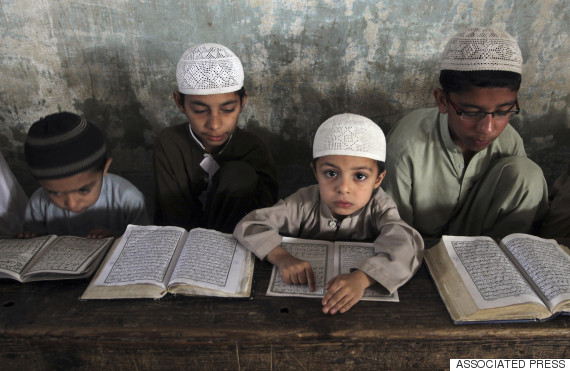

But the terrorist mindset cannot be eliminated through force alone. There has to be a multi-pronged response, which includes attention to rule of law, due process and the overhaul of curricula at schools and religious seminaries that propagate an extremist mindset.

Punjab Law Minister Rana Sanaullah insists that all 15,000 madrassas in the province have been scrutinized and are not engaged in any "anti-state activity." But then again, he is one of the many politicians who broker electoral alliances with extremist groups to get more votes.

The Pakistani electorate has consistently rejected religious parties at the polls, bringing very few of their candidates to the assemblies. Religious parties in the political system as well as those that reject democracy are united against any moves towards pluralism and inclusivity. This includes the recent parliamentary resolution to declare the Hindu festivals of Holi and Diwali, plus Easter, as holidays, and the provincial Punjab Assembly's women's protection bill that would provide redress against gender violence.

Pakistan must empower its police to counter crime at the local level -- such as attacks on barbershops for shaving men's beards -- which feeds terrorism on the larger stage.

Gender violence often takes place on the pretext of honor, and there is widespread impunity, if not in law then in practice. Such impunity also applies to violence on the pretext of the honor of religion. Inaction against perpetrators is particularly obvious when they target the persecuted Ahmadi community, which was declared non-Muslim by a constitutional amendment in 1974. Last December, for the first time, the government removed posters from shops banning the entry of Ahmadis.

Pakistan must move to redress these injustices, including addressing the anti-Ahmadi legislation in its constitution, which continues to fuel the extremist mindset.

Simultaneously, as I've argued before, Pakistan must empower, train and equip its police force to counter organized crime at the local level and counter the extremism that feeds terrorism on the larger theater -- attacks on barbershops for shaving men's beards or on shops selling music videos, defacing women's faces or limbs on billboards or attacking a Valentine's Day activity.

Since the 1990s, when the religious right began misusing blasphemy laws systematically in pursuit of their political agenda, vigilantes have killed over 60 people who allegedly committed "blasphemy." Some, like Taseer, were never charged and tried. Others were killed after being acquitted or by other prisoners or even by prison guards. Victims include lawyers and judges.

Qadri is the first to be punished for such a murder. Reservations about the death penalty aside, taking that step indicated the government's resolve to not be bullied by extremists. The dharna in Islamabad will test this resolve.

Chants of "Go Nawaz go!" targeting the Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif are reminiscent of the dharnas in 2014, led by opposition politician Imran Khan and the Canadian-Pakistani cleric Tahirul Qadri (no relation to Mumtaz Qadri). Both were seen as being supported by the security establishment that still controls much of Pakistan's policies behind the scenes.

Their demands undermine rule of law and constitutionality in Pakistan.

These protestors' slogans are also targeting the army, forcing the more mainstream Jamat-e-Islami to distance itself from the event that it initially supported. Protestors are also using abusive language towards women in Sharif's family.

Their demands undermine rule of law and constitutionality in Pakistan. They want Pakistan to officially declare Qadri as a martyr, execute Aasia Bibi (her case is pending in the Supreme Court), release their activists (some 200 have been arrested), remove all Ahmadis from government service and expel them from the country.

Attacks like the one in Lahore will not end by appeasing such anarchists. Any move to do that will undermine the democratic political process upon which the country has embarked since the last two elections. That is precisely what the extremists want. To counter them, Pakistan must stay the course -- the democratic political process in the long run is an antidote for extremism. The international community must support this.

Earlier on WorldPost: