Mainstream society, especially on the Internet, has taken an enormous amount from the culture of espionage. We now routinely use multiple passwords, aliases, and disguises. We also employ a vast arsenal of techniques for both identification and deception. Simply to survive, we must constantly be suspicious. Emails arrive in our inboxes every day with offers of love and money, but very few, if any, of them are sincere. Almost every photograph we see in slick publications has been edited with Photoshop or a similar program, making the apples more red and the human models more perfect.

So why aren't we all totally paranoid? Because the espionage and the deceptions are all very impersonal. There is little sense of trust, so we do not feel perpetually betrayed. The NSA, and perhaps even Facebook, collects information on a scale that even Stalin's secret police could never dream of, but the persons disappear into a mass of data. Old-fashioned spying and counter-espionage required empathy, since, in order to anticipate their moves, you had to understand the psychology of your adversaries. This created emotional conflicts, ethical dilemmas, and high drama, of the sort that fills the novels of John Le Carré. There are still spies and agents that operate more-or-less in the traditional way, but spycraft is now mostly a matter of looking for patterns in vast numbers of digitalized communications.

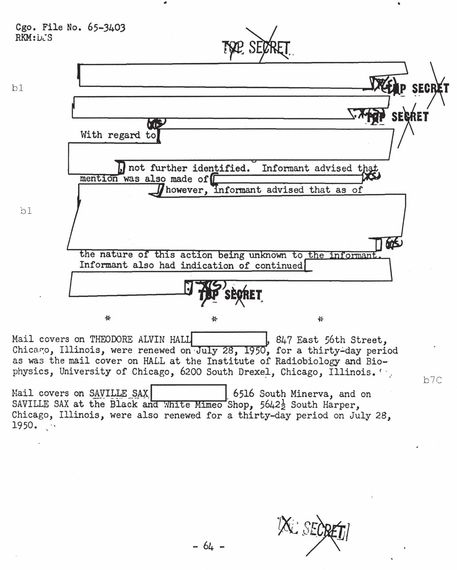

When I was growing up, the FBI was constantly following my father and mother, tapping their phone, looking though their garbage, and interviewing their acquaintances. As I child, I had no idea that this was going on, but that simply made the ubiquitous paranoia even more difficult to deal with. The FBI has by now released to me about 700 out of more than 3000 pages that it collected on my father's case from the mid-1940s through the late 1960s, and these are often so heavily redacted that only an odd phrase or two is readable. The files are written in bureaucratic prose, but there is nothing slick about them. They have a sort of quirky, arbitrary quality that at least shows the humanity of their creators. They were produced on manual typewriters, in which the spacing and the characters are slightly irregular. Several arrows, lines and occasional notes are written in pen. On the older files, the tape that covers censored passages is very irregular in shape and obviously cut by hand, but in the later ones it is standardized.

While I do not have nearly enough information to tell for sure, I suspect that reasons for the many deletions may be at least as personal as they are political. The passages may have simply reminded a bureaucrat of something that was unpleasant to her. In the margins of the files are codes, supposedly indicating why passages were redacted. The code "b1" indicates it is a matter of national security, while "b2" means a reason that pertains to the internal workings of the FBI. The code "7d" indicates that the passage was blocked out to protect confidential sources, while "7c" indicates that releasing the information would be an unwarranted invasion of someone's privacy. But these categories are usually too general to be very helpful without the full context and a great deal of interpretation.

The culture of the FBI must have been primarily an oral one, in which items were committed to print mostly as an aide to memory. The released files consist almost entirely of disconnected facts, which would, in any other context, appear trivial, except that they are dramatically highlighted by designations such as "secret" and "top secret." It is just about impossible to extract any narrative thread from them. They contain almost no analysis whatsoever. I estimate that the part of my father's FBI file that was released to me was about a tenth of the total, and it might have been even less. But if the rest contains simply more of the same thing, the entire file might not tell me a lot about my father's case, or at least not unless it was studied with a great deal of diligence and expertise.

Nevertheless, FBI files will probably be, in many ways, among the most important documents for future, and even present-day, historians, and obliterated passages, even should their content never be revealed, may ultimately be more illuminating than ones that were spared. They are not only full of the paraphernalia of everyday life, but also reflect many common fears. One could frame pages from them and hang these on the wall as semi-abstract graphics, giving them names like "Paranoia."

***

A page from the FBI file of Saville Sax, as reproduced in the book Stealing Fire: Memoir of a Boyhood in the Shadow of Atomic Espionage by Boria Sax (Decalogue Books, 2014):