The choice between a 1.5 and two degree C global warming target means choosing between different futures for our food system. Photo: Neil Palmer (CIAT)

World leaders are now debating whether to aim at limiting global warming to two degree C or 1.5 degree C. But nobody is talking about what these different targets mean for future agricultural production. When it comes to food and farming, a 1.5-degree C warmer world is vastly different than a 2-degree C warmer world.

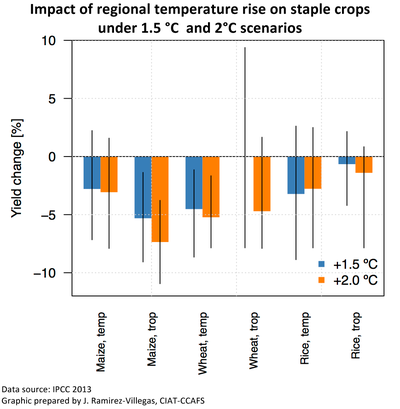

We calculated the difference based on the latest data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which shows that half a degree C is going to hit some staple crops worse than others.

Tropical maize, a staple in many parts of Africa, shows the biggest sensitivity to the extra half degree C, with yield declining on average more than 50 percent between 1.5 to 2 degree C. Wheat production in temperate regions like Europe, China and North America, will be hard hit overall by climate change, declining approximately 4 percent between 1.5 degree C and declining slightly more than 5 percent at 2 degree C.

The differences are smaller in temperate maize. Meanwhile, rice grown in temperate regions may slightly increase yields in a 2 degree C warmer world, compared to a 1.5 degree C warmer world. While large variation in the data suggests that this is not bound to happen everywhere, the differences in the regional means are clear.

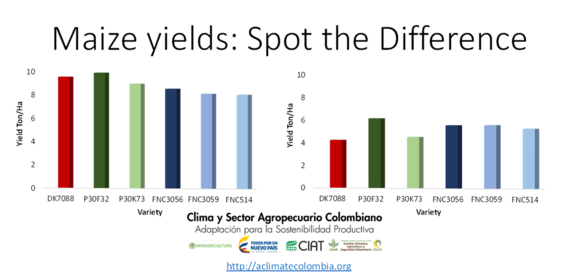

Another way to look at it is in the chart below, which compares maize yields from field trials in Colombia. The data were taken at two locations where the only difference was that one (in the right panel) had maximum temperatures of 1 degree C above the other. All maize varieties and hybrids showed reduced yield from warming, with some showing 50 percent loss or more.

An extra half degree C spells more extreme weather

What is more worrying is the increase in climate extremes that an extra half degree C is likely to bring. This potentially means more frequent heatwaves, droughts, floods, cyclones, all disastrous for farmers, particularly in the tropics.

Adapting farming to a warming world

One way to safeguard our food from future climate impacts is through breeding more adapted and climate-resilient crops. We've seen many promising developments for heat and drought resistant varieties of maize, and rice varieties that tolerate submergence in salt water, to cope with sea level rise. But an ongoing analysis by the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) is finding that crop breeding in Africa and across the tropics is already failing to keep up with the current rate of warming. This means that most crop varieties will not be ready for either a 1.5 or a two degree C temperature rise. Adapting to to lower warming rates such as a 1.5 degree C target would, however, require less effort.

Whether 1.5 or two degree C, we need to urgently invest in safety nets so farmers can arm themselves against current and longer-term losses. This includes weather index-based insurance for crops and livestock; climate advisories to help farmers decide what to plant, when to plant, and when to harvest. In some cases farmers will need to move to new areas or abandon farming altogether. The more we can anticipate local impacts, the more that countries can help farmers plan ahead.

Reducing emissions to keep global temperatures down

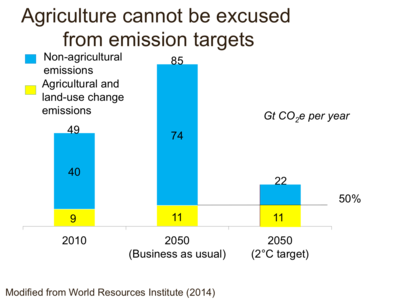

The target we choose will also shape our efforts to reduce greenhouse emissions - a 1.5 degree C target will require even more effort from the agriculture sector. Even with a two degree C target, by 2050 we will likely run out of existing options for reducing emissions from the industrial, transport and energy sectors. Reducing emissions from agriculture will be imperative - in fact it will be impossible to stay even within a two degree C target if agriculture does not contribute its fair share of reductions.

There are enormous opportunities for reducing emissions from agriculture, for example from paddy rice production in Asia. In Vietnam, for example, we've shown it's possible to reduce emissions and save water, while maintaining or even increasing rice yields. In most cases we know what works where - what's missing is urgent investment into large scale initiatives.

Action needed now, no matter what the target

Leaders in Paris must understand that 1.5 and 2 degree C are not arbitrary targets when it comes to our global food system. Food and farming will change fundamentally depending on leaders' political ambitions. While the precise numbers in our analysis are subject to ongoing revision, the differences between 1.5 and two degree C offer a glimpse of the different futures that we can choose between. No matter what, time is of the essence -- the planet will increase in temperature by 1.5 degree C about 13 years sooner than it will hit two degree C. A 1.5 degree C target is more ambitious, expensive and difficult to maintain than a two degree C target. Policy makers should carefully consider the implications of both and plan for large scale and transformative action. Setting overly ambitious targets could undermine economic development, but setting a weak target, or worse, setting no target, will have devastating consequences.