I grew up in the south of Romania in the 60's in a small town that was thriving and well cared for. People had comfortable lives with all kinds of food available, including meat, chocolate and fruit. We had TV that broadcast great shows and cartoons from all over the world, mainly the US. The brand of communism we lived with seemed benign and idealistic. The streets were paved, clean and lined with trees, the parks well tended, and the homes quite lovely. My father was a believer in the good of the system, and both he and my mother taught in schools that were functioning and practical. Outside of Yugoslavia, I think Romania in the 60's was among the luckier of the countries in the communist world. But unlike Yugoslavians, we were not free to travel or express ourselves so openly.

In the 70's things started to change. I was invited to join the Pioneers, an invitation one couldn't refuse. It was like a scout group for children to be indoctrinated in the communist system and my most vivid memory of it now is a transformative moment when, as part of the Pioneers, we were told to do a homework assignment and write an essay about the happiest day of our lives: the day we became Pioneers. I had no idea what to write. That day was not my happiest, in fact I couldn't imagine what day would classify as my happiest at that young age, but I knew it wasn't that one. I asked my mother for help and she told me to stop being fussy and just do the assignment. This is when I realized the system needed us to lie in order to get by.

As Ceausescu grew more extreme in his methods he started implementing some crazy schemes and ideas. One involved the concept of saving everything - for what I don't know. But suddenly things that had been in abundance started to become rare, and between the mid 70's and the mid 80's the country rapidly declined, and in order to help ensure that those plans would not be sabotaged or derailed, the regime also grew more repressive. Information became controlled to a much greater degree, and the security police system known as the Securitate grew exponentially. People were drafted to act as informants, so that soon no one knew who to trust, as your best friends or relatives could inform on you. Fear increased together with the lack of services and food.

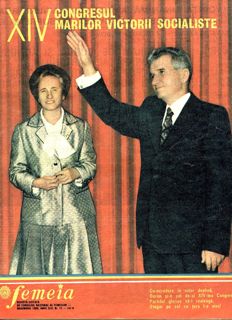

It became harder to find meat; beef disappeared, then pork, and finally even chicken, so that in the shops all you could eventually find were poultry necks and feet, the parts usually thrown away. Eventually even those would vanish from the shelves. Fruit and vegetables became scarce, unless you had a patch of land and grew them yourself, and pleasures like chocolate disappeared completely. TV was controlled and limited, until eventually it only ran two hours per evening, and those two hours were dedicated to propaganda and footage of the dictator and his wife and their visits to factories and towns.

In the late 70's, early 80's I moved to Bucharest to go to university there. At first I lived in a dorm and ate in a student cafeteria. Initially I loved the city, for its wide boulevards, wonderful architecture, lovely riverbanks, charming old neighborhoods and wondrous parks. But Ceausescu's schemes soon put an end to those charms: to build his megalomaniacal "people's palace" he razed entire neighborhoods, compelling thousands upon thousands of people to leave their homes and move into crowded, decrepitly built new apartment blocks on the edge of town. Parks disappeared, people abandoned their dogs and cats onto the streets, and the city became a giant construction site for a decade. (The palace was still unfinished when the dictator was killed years later). The river was cemented up, trees chopped down, and block after block of horrendous apartment complexes were constructed. It was the utter demolition of a lovely capital city, once called "Little Paris," and the brutality of this horror was only compounded by the difficulties of daily life. Food was scarce, the shops shelves empty. Once I recall that the only thing available were jars and jars of mustard. No bread to spread it on, no meat to eat with it. When something would appear and become available word would spread quickly and lines would form from the early hours of the mornings. I found myself standing in line often and once I fainted waiting for strawberries. Later when I went to visit my father in my hometown, he tried to please me by getting oranges, so he waited in line for hours, only to see the last ones go to the person in front of him. He returned home with tears in his eyes. Like many people, he soon understood that the beloved dream of an ideal communist society was turning into a nightmare.

With these lines and suspicion came the decline of civil society. If you had to wait in line for crumbs of something you would fight for your spot. The most aggressive would dominate, and groups would overpower individuals; as a result it was not uncommon for some people to work in groups and get all the food available, then resell it on the black market for a profit. A culture grew that promoted a mentality where it was every man for himself, a tragic reversal of the communist ideal as the communist state became more repressive and oppressive.

There was no revolt like in 1956 in Hungary or 1968 in Czechoslovakia. Perhaps this is because until the mid 70's things were almost OK, but the degeneration came fast and furious. By then there was no opposition, no chance to organize against the regime, no way to communicate, no tactic one could use to speak out, not even in one's own family, for fear that your cousin or sister or uncle was a spy for the dreaded Securitate. Indoctrination became harsher, and money vanished. Later I learned that one reason for the poverty, disappearing goods and services and decline of quality of life had to do with Ceausescu's obsession with avoiding any form of government debt. He preferred to export and sell off everything we had, starving the people in the process. So we had next to nothing, and then nothing. When the electricity was cut, there was a run on candles; then you couldn't even buy those. People would try and heat their places with gas, but that too disappeared. The streetlights went off at night, the country was plunged into darkness, on every level.

When the Berlin wall fell we knew nothing, as all media information was limited and controlled. And yet the people in power knew that the writing was on the wall. They debated internally as to whether it would serve their interests to support Ceausescu and his hated wife Elena. Many now presume his colleagues decided to make him the sacrificial lamb and save their own skin. These were the decisions that led to what many believed at the time was a true revolution in Romania, but which we now understand was nothing more than a creative coup d'etat.