The timely and thought-provoking exhibition Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance and the Camera Since 1870 -- currently on show at SFMOMA through April 17 next year -- explores the use and cultural impact of photography made in public spaces. A thorough examination of a powerful subject, the show inspires us to examine and question how we feel as individuals and a collective about watching and being watched. It also makes clear the huge impact cameras and camera technology has had and continues to have on us.

Exposed is co-organized by SFMOMA and Tate Modern (where it débuted in May), and comprises over two hundred images with works by artists, amateurs, professional journalists, and governmental agencies. The exhibition was conceived by SFMOMA Senior Curator of Photography Sandra S. Phillips and co-curated with Tate Curator of Photography Simon Baker. Just prior to the show's SFMOMA opening, I did a walk-through with Phillips to gain insight on the show and learn about the stories behind the images.

Chérie Turner: What was the impetus for this show?

Sandra S. Phillips: That's what everyone wants to know. I did a show a little more than fifteen years ago called Police Pictures, and it's about the way we think photographs are objective truths, and they're really not. This idea was the next obvious one -- to look and see if the camera has made us see in ways we wouldn't maybe ordinarily see and what it means culturally for us, too. If there's a way we look at the world differently because we're seeing it through a camera lens.

Can you talk about how the show is divided.

There are five sections [The Unseen Photographer, Voyeurism and Desire, Celebrity and the Public Gaze, Witnessing Violence, and Surveillance]. The first [The Unseen Photographer] is really about the beginning notions of what privacy is in public spaces. We are sensitized to having a sense of privacy because photography exploded that and abused it.

In 1870 it was possible suddenly to make a camera small enough that you could conceal it and film fast enough that you could record movement. There were all these amateurs all over the place who were making pictures that were very invasive. The laws said that an American citizen has a right to privacy except in a public space. So that's why there's this tradition of street photography, especially in the United States.

So a lot of these pictures here were taken with concealed cameras [several such cameras are on display] -- looking at people when they were sleeping or drunk or when they were poor.

Man, Five Points Square, New York, 1916 by Paul Strand, 1916

This one is one you shouldn't miss [Man, Five Points Square, New York, 1916]. It was done very early with a box camera that had a false lens on the front and the real lens on the side. It's an invasive picture. The photographer's looking at someone's private anguish. And obviously many of the people in these images are poor--that's another inegalitarianism.

[New York by Garry Winogrand, 1969

Collection SFMOMA, fractional and promised gift of Carla Emil and Rich Silverstein; © Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

This is interesting [New York] because the photographer uses a wide-angle lens, and of course, the couple doesn't realize they're being photographed. They think he's taking just her picture.

It's creepy.

It is creepy. So then we have these different sections where we look more deeply. [Moving on to the Voyeurism and Desire section.] This is the sex room. There's Andy Warhol's Blow Job film, and it's just a guy's face. You can imagine what's going on, but we don't know for sure.

I know you have a bit of a reputation for including difficult or challenging photos; I'm thinking here about the torture or violence photos in this show as well as the sex images. Can you tell me why they interest you and why you think they're important for us to look at.

First of all, I don't think they're all that difficult. We see most of this on the web all the time. They're not unusual, they're just in a different context here. And the reason they're here is because I want people to think about them. I think they're very beautiful.

One issue here is, How important in photography is it for the photographer to be an artist? I don't think it's important at all. I think the only thing that matters is the picture. And the picture can be taken by a robot or a child or a master photographer. This show is really about ideas as much as it is about pictures. That's why they're here. They're here to be provocative and to promote discussion and thought. There are some creepy pictures, but I think they're probably creepy because our culture is creepy. Many of these pictures were published in newspapers and magazines. It's shocking we tolerate it.

We get to face that here, too.

This section [Celebrity and the Public Gaze] is about celebrity and the double-dealingness of celebrity. Celebrities, to be celebrities, need a public, and they need to show their privacy to the public because that's what the public wants.

The Queen Plays with her Corgies from the series Confidential by Allison Jackson, 2007

Courtesy the artist and M + B Gallery; © Alison Jackson, courtesy M+B Gallery

These pictures [by Alison Jackson] are completely made up. They're not real. They're made with people who look like, say, the Queen.

[Moving on to the Witnessing Violence section.] One thing about this part of the show is that it demonstrates the violence and change in the sixties. There was a lot of sixties trauma that's depicted that everyone got acclimated to; you saw people getting mangled by dogs and the Vietnam War.

Then we come to the first of the surveillance rooms. We start with history here beginning with the Civil War.

Criminal Record Office, Great Britain, Surveillance Photograph of Militant Suffragettes, ca. 1913

Collection and © National Portrait Gallery, London

Then, here [Surveillance Photograph of Militant Suffragettes], very early in the twentieth century, late nineteenth century, the police had these files on dangerous persons, like suffragettes or anarchists.

And then the technology improves, so you can have pictures taken of people in courtrooms or private meetings, without their knowing. And then this is Cold War stuff; here are real spy pictures.

Rudolph Herrmann (Dalibar Valouschek), [FBI surveillance photograph, Soviet KGB agent at dead drop (meeting place), Westchester, New York], ca. 1980

National Archives, Washington, D.C.; courtesy National Archives, photo no. 065_CC-48-3

I like them because you really can't tell what happened. They're completely ambiguous. They're supposed to say something and they really don't.

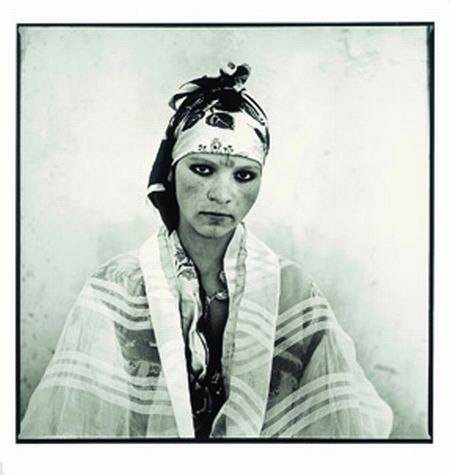

Marc Garanger, Femme Algerienne, 1960

collection SFMOMA, Accessions committee Fund purchase; © Marc Garanger

And these [images by Marc Garanger, 1960] are interesting. The photographer is a French soldier, who, during the Algerian War was sent to photograph woman to keep police records of them. Everyone had to have an identification card. And these are women whose faces had not been seen by anyone except their families. He had to insist that they take their veil off and be photographed. So two things that these women don't appreciate, that kind of invasiveness and the graven image thing. The experience of doing this radicalized the photographer. He now uses these as documents of how we shouldn't treat people.

Looking through these surveillance images, a lot of what this show is about is technology.

But also the meaning of technology and what technology looks like. You have to see it to be able to understand it. In the next room are more personal investigations of surveillance. This is a very interesting piece by Yoko Ono where she follows this person. It's called Rape, but she's just following someone.

Again with the creepiness.

It is creepy, but it's also fascinating once you get into it.

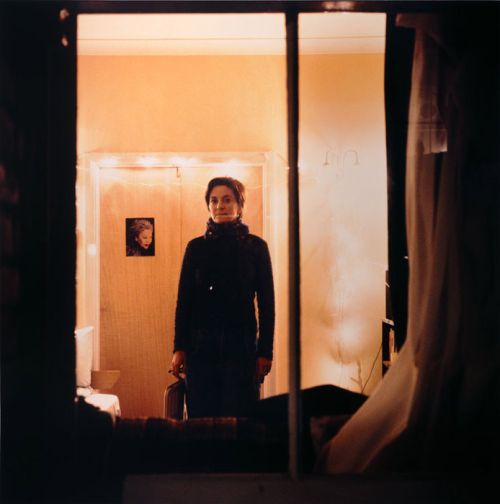

Shizuka Yokomizo, Stranger No. 2, 1999

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Accessions Committee Fund purchase; © Shizuka Yokomizo

These are other images [work by Shizuka Yokomizo] that you feel like you really shouldn't be looking at because they're so invasive.

Well, she's this little Japanese lady and she writes to these people and says, "I'd like to take your picture through your window at night. And if you don't want me to, just close the curtain." She never actually talks to them directly. She just leaves this note in the mailbox. Of course, they can't see her --

But they seem to be looking right at her. So, we've reached the end of the show here. Is there anything in particular that you would like the viewer take away from this show or think about.

I think the thing to think about is how powerful this is in our culture. How much a part of our culture it is. It's infiltrated our lives. And, we might want to think about that. Not to be judgmental, but to understand what it means to us as a culture.