As far back as he could remember, Auguste Rodin loved to draw. When it came time for him to prepare for a career, his parents sent him to a school of commercial art. There, he recalled, when he saw artist's clay for the first time, "I thought I had gone to heaven." His love for clay would make him the greatest sculptor of the modern era, and perhaps the greatest modeler in the history of Western sculpture. Yet he never abandoned his first love, and he produced vast numbers of drawings, from all stages of his career. Paris' Musée Rodin alone possesses 4,300 of his drawings, from the artist's donation to the State at the end of his life. It is currently displaying 300 of these, made during 1890-1917, in an exhibition titled Capturing the Model.

Ange ou Ariel, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), Musée Rodin

Rodin was an experimental artist, and he did not make preparatory drawings for his sculptures, but rather worked directly in the clay. Thus the scholar Albert Elsen explained that "Drawing did not serve Rodin as the blueprint for his sculpture," but that it was an independent and related activity: "Drawing and modeling were distinct yet mutually supportive and cross-fertilizing in his art. Seeing and feeling the model's profiles through the point of his pencil and hands gave conviction to his fingering of the clay."

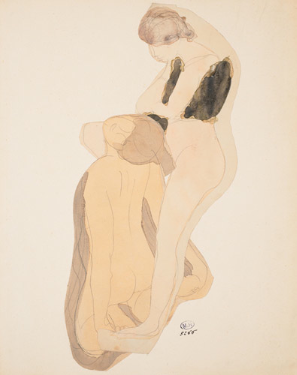

Couple féminin, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), Musée Rodin

Rodin's drawing mirrored his sculpture in that it was a wholly visual activity, carried out exclusively under the inspiration of the human body: "I can only work from a model. The sight of human forms feeds and comforts me."

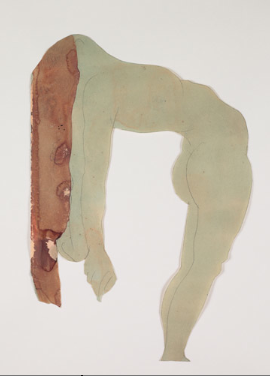

Femme nue aux longs cheveux, renversée en arrière, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), Musée Rodin

As is typically the case with experimental innovators, Rodin's art matured slowly, and he was at his greatest late in his life. His Monument to Balzac, created during 1891-98, when Rodin was in his 50s, is generally considered his most important contribution, and the drawings currently on display at the Rodin Museum date from this period. They consequently illustrate a number of interesting features of the mature working process of a great visual artist at the height of his powers. One of the most striking of these was described by a writer who watched Rodin work in 1903:

Equipped with a sheet of ordinary paper posed on a board, and with a lead pencil--sometimes a pen--he has his model take an essentially unstable pose, and then he draws spiritedly, without taking his eyes off the model. The hand goes where it will: often the pencil falls off the page; the drawing is thus decapitated or loses a limb by amputation...

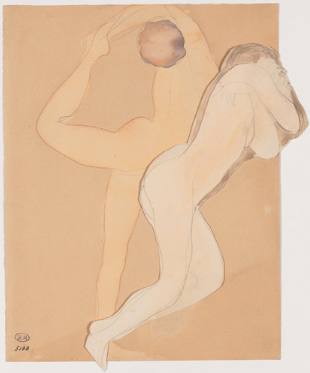

Femme nue penchée sur une femme agenouillée vue de dos, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), Musée Rodin

Rodin himself explained the reason for this practice:

What is this drawing? Not once in describing the shape of that mass did I shift my eyes from the model. Why? Because I wanted to be sure that nothing evaded my grasp of it. Not a thought about the technical problem of representing it on paper could be allowed to arrest the flow of my feelings about it, from my eye to my hand. The moment I drop my eyes that flow stops.

Psyché, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), Musée Rodin

Rodin's "instantaneous drawing" was a response to a problem that has troubled many exacting experimental artists. The critic David Sylvester explained that "Working from life is [actually] working from memory: the artist can only put down what remains in his head after looking." Sylvester understood that this caused "the despair known to every artist who has tried to copy what he sees." An example was Paul Cézanne, who told Joachim Gasquet, "Everything we look at disperses and vanishes, doesn't it? Nature is always the same, and yet its appearance is always changing." Another was Alberto Giacometti, who told an interviewer that "In fact, one never copies anything but the vision that remains of it at each moment, the image that becomes conscious." (Interestingly, Virginia Woolf understood this problem, perhaps because of her close friendship with the critic Roger Fry, who was also a painter. Thus in To the Lighthouse, Woolf wrote of the experimental painter Lily Briscoe that "She could see it all so clearly, so commandingly when she looked," but that "it was when she took her brush in hand that the whole thing changed. It was in that moment's flight between the picture and the canvas that the demons set on her.")

Elsen recognized that Rodin's practice was a visual perfectionist's response to this problem: "Rodin's practice of drawing without looking at his pencil was inspired by an obsession with capturing not just movement but, more important, the quality of wholeness in what he saw. He did not have to rely upon memory, and he was forced to eliminate all that was trivial in the race to fix the figure in a large, rhythmical contour."

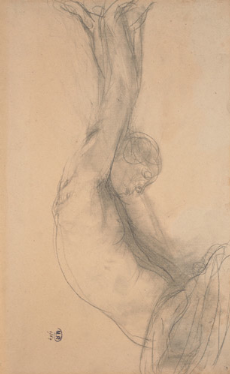

Torse de femme nue, de profil à droite, les bras dressés au-dessus de la tête, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), Musée Rodin

Rodin authorized a number of exhibitions of his drawings in the last decade of his life. Yet for the most part his drawings were not intended for public display: Kirk Varnedoe concluded that they were "first and foremost private sources of education and pleasure for the artist." Nonetheless, Rodin believed that the spontaneity of his drawings could inspire other artists, for their freedom "will give more liberty to artists who study them, not in telling them to do likewise, but in showing them their own genius and giving wings to their own impulse, in showing them the enormous space in which they can develop."

Rodin's drawings are consistently fluid, with sweeping lines, spontaneously creating movement. They give the viewer a feeling of immediacy, sensing the artist's hand passing rapidly over the paper, repeating contours for emphasis, as a great experimental artist embodied in them the results of a lifetime spent creating material representations of what he saw.