Paradoxically, Gustave Caillebotte was the odd man out among the French Impressionist painters. This in spite of the fact that he was an enthusiastic and effective participant in the group's activities, and made major contributions to its struggle for recognition and eventual success. Caillebotte not only exhibited his work in five of the group's eight independent exhibitions held during the 1870s and '80s, but also made financial contributions that made several of the exhibitions possible. The son of a wealthy manufacturer, Caillebotte was a key early patron of the Impressionists, in the process amassing the remarkable collection that today comprises the core of the holdings of the Musée d'Orsay. He was respected both personally and professionally. When Caillebotte died at the age of just 46, Pissarro wrote to his son Lucien that "he is one we can really mourn, he was good and generous, and a painter of talent to boot." Yet Caillebotte was never considered a true member of the inner circle of the Impressionists. Art scholars have long recognized this, but have never fully explained it.

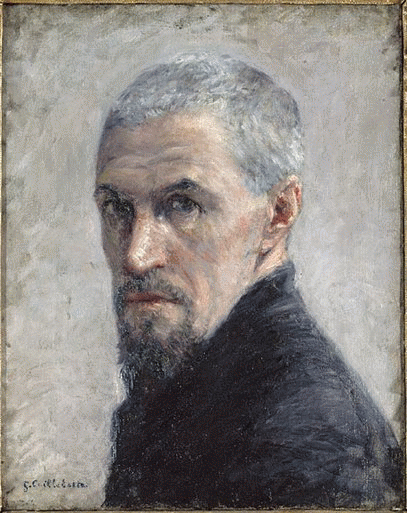

Portrait de l'artiste, Gustave Caillebotte, 1889, Musée d'Orsay

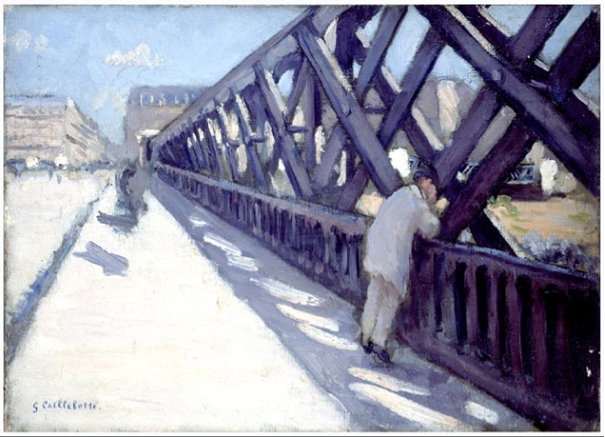

Prime evidence for the resolution of this paradox was provided by the late Kirk Varnedoe, who looked carefully at Caillebotte's paintings, and studied the process by which they were made. In a celebrated early essay, Varnedoe described Caillebotte's technique as "photographic in quality," and he later explored the methods that produced this effect. In a 1987 monograph on Caillebotte, Varnedoe contended that the artist began his paintings by tracing guidelines from photographic images, then used these as the basis for complete perspective diagrams, created with straight-edges and geometric calculation. Varnedoe also documented the numerous detailed preparatory drawings and oil studies of the central figures in his paintings.

Caillebotte's relationship with photography is underscored by

a current exhibition at Paris' elegant Musée Jacquemart-André, which features both Gustave's paintings and the photographs of his brother Martial. The two brothers' shared interests -- in yachting, gardens, and life in the modern city -- often led them to produce images of the same subjects, from similar points of view, and the exhibition places these side by side. Detailed comparison might prove rewarding, for a technical note in Varnedoe's monograph observes that several paintings by Gustave originated in small drawings on tracing paper, close in size to the photographic plates Martial often used. Perhaps Martial's photographs were sometimes part of Gustave's process in making paintings.

Sketch for Le Pont de l'Europe, Gustave Caillebotte, 1876, Musée des beaux-arts de Rennes

Kirk Varnedoe's careful analysis of Caillebotte's technique provides the basis for understanding why Monet, Pissarro, and the other Impressionist painters could not consider him a true member of their group. Impressionism was an experimental innovation: Monet and Pissarro were committed to direct execution of paintings of open-air motifs, made without preparatory studies or drawings. Their paintings were records of what they saw, and this required observation of their subjects throughout the process of producing their paintings. In contrast, Caillebotte's method identifies him as a conceptual artist, who planned his paintings carefully, basing them on formal analysis and calculation as well as on photography. Caillebotte's extensive and complex construction of his paintings must have been carried out primarily in the studio, rather than in view of the motif. Tellingly, Varnedoe observed of Caillebotte's masterpiece, Paris Street: Rainy Weather, now in the Art Institute of Chicago, that "Its scale, method, and structure stand outside the Impressionism of the 1870s and relate more closely to the principles of the Neo-Impressionists of the 1880s. Indeed, the relation between the Rainy Weather and Georges Seurat's Sunday on the Island of the Grand Jatte seems quite striking." Varnedoe's insight is correct, for the conceptual Rainy Weather is artistically closely related to Seurat's conceptual masterpiece, and has little in common with Monet's experimental Impressionism. The photographic precision of Caillebotte's work stands in sharp contrast to the calligraphic touch with which Monet represented the imprecision of real vision.

Paris Street; Rainy Day, Gustave Caillebotte, 1877, Art Institute of Chicago

Although the Impressionists liked Caillebotte, and appreciated his support for their project, they understood that artistically he was not one of them. To painters for whom the essence of their art lay in spontaneity and vision, an artist who relied on planning and calculation could never be a true artistic ally.