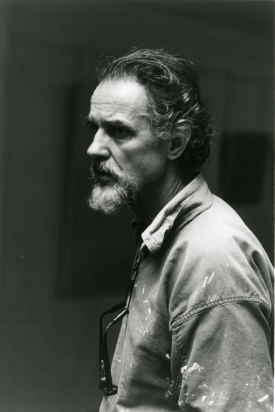

Jon Schueler, 1981, photograph by Archie McLellan, © Jon Schueler Estate

The Sound of Sleat is a body of water in western Scotland, between the mainland and the Isle of Skye. The Sound of Sleat is the best book I have ever read about an American painter.

When Jon Schueler first went to Mallaig and saw the Sound of Sleat in 1957, he wrote to his wife that "this part of Scotland is exactly what I wanted -- visually. I have everything I could hope for." He had been dreaming of going to the Scottish Highlands for 15 years, since 1942, when he had met Bunty Challis in London, at a tea dance for American officers. Schueler was a navigator in the Army Air Corps, flying bombing raids over France and Germany; Challis was an emergency ambulance driver in London. Both were married -- Schueler to a woman he had met only months before, during basic training, Challis to a submarine commander she hadn't seen in two years -- but they had a brief but intense romance in London during the blackout. From 1957 until his death 35 years later, Schueler would return frequently to Mallaig to paint. He was often asked why he had gone to Scotland in the first place. He would answer that the story began with the memory of a beautiful woman:

She was English, but she loved Scotland. And because she understood something very personal about me, she thought I would love Scotland, too. Most particularly, she thought I would love the Highlands, and often she would describe them to me. I created the most powerful images from her descriptions. They were images of a sea and land and sky beyond mystery.

When I left England, the images stayed with me... In New York, as an abstract painter absorbed with the idea of Nature, I created glimmers of fantasy sea and sky, storm and fog, sun and land, which became the sky. More and more, I felt that I had to go to Scotland, I had to discover the Highlands in reality, I had to live inside my painting.

Jon Schueler, The Search: Bunty's Blues, 1984, 79 x 72 inches ( o/c 1411), © Jon Schueler Estate

The Sound of Sleat is a selection from a manuscript of 2700 pages that Schueler wrote over more than 20 years, in the form of a journal, memoir, and letters. After his death in 1992, his widow, Magda Salvesen, and a friend, Diane Cousineau, turned portions of Schueler's manuscript into a 350-page book that was published in 1999. The result is a fascinating account of the life and times of an American artist.

Jon Schueler, Edinburgh Blues, 1981, 79 x 75 inches, oil on canvas (o/c 1188) Collection Union College, Schenectady, © Jon Schueler Estate

Schueler was a second-generation Abstract Expressionist. He became a painter in San Francisco, where he studied with Clyfford Still, whom he revered. He moved to New York in 1951, and through Still soon met all the Abstract Expressionists. Schueler had many quintessential experiences of the time and place: Barnett Newman helped him find a studio; he was puzzled at Mark Rothko's sudden shifts from warmth to hostility; he was insulted by Norman Mailer at a cocktail party in Provincetown; he loved to listen to Franz Kline talking nonstop over beers at the Cedar Bar, even when he wasn't sure what Kline was talking about; he had a one-man show at Leo Castelli's new gallery in 1957, and again in 1959; he exchanged studios in Paris with Sam Francis; he made love -- once -- with Joan Mitchell, and more frequently with a number of beautiful young women who found philosophical artists romantic and irresistible. Schueler's journal consequently provides an insider's view of an exciting time, when New York was becoming the center of the art world. And it is more eloquent than most such accounts, because of Schueler's unusual skills: he had a master's degree in English literature from the University of Wisconsin, and intended to become a professional writer before World War II disrupted his plans. His portrayal of the art world benefits greatly from his early training. In 1962, for example, he reported a conversation:

Last night, de Kooning said that his ambition in life was to be a good painter. That he worked hard to make a good picture. That was all. He said he had no trouble working in those terms, and he was satisfied to have that as the extent of his goals. No big idealism, no searches, no mysticism, no power, no trying to be a great thinker, etc. Well, of course, he's succeeded, being one of the best and most successful living painters. I was impressed with the humility of the drive.

But Schueler lived in a complex world, and never stopped with a single view of any subject. So he soon circled back to de Kooning's declaration:

I can't help but think that Bill protests too much, and that even his conscious needs are greater... Bill is certainly extremely competitive, and his modesty in this department always comes off as a shallow disguise. Pollock used to scream in drunken agony of his superiority to other artists. [Clyfford] Still labors through tortuous logic to prove his superiority.

Jon Schueler, Far Away Blues, 1986, 65 x 72 inches, oil on canvas (o/c 1482), © Jon Schueler Estate

And here is Schueler in 1972, reflecting on the ubiquity of influence even in the crucible of New York in the '50s:

We were all derivative then... [We] couldn't admit it... because originality was the password. The difficulty was that we were not always what we said we were. I was derivative of Clyfford Still and later in some ways of Rothko and certainly of Turner... Kline and de Kooning were derivative of each other. Barney Newman of Still and Rothko...

[James] Brooks dug Pollock. Pollock the Impressionists. De Kooning the Cubists. Everyone dug someone. But, also, everyone was bursting out of chains, ropes, bonds, blindfolds. The most was wanted. The highest drama. The most beauty... The scratch in the paint, the paint dripping, the hand moving across the canvas, the precious memory of the hand, all of these things are beautiful. We want to see beauty. What is beauty, here in America? we asked.

Jon Schueler, Skywards, 1969, 34 x 58 inches, oil on canvas (o/c 69-53), Courtesy David Findlay Jr. Fine Art, NY

In an era in which art has ceased to be heroic, many people are nostalgic for a time when artists could speak without irony of truth and beauty. One sign of this attitude is the current exhibition of Abstract Expressionism at the august Museum of Modern Art, where you can look at products of that time. But if you want to feel and hear how the art world seemed when giants walked the streets of New York, and drank in the Cedar Bar, read The Sound of Sleat. And if you do, you will get more than a vivid historical document, for it is also an extraordinary portrait of an experimental artist. I will write about this soon.

Jon Schueler, Blues for Oscar, 1982, 44 x 65 inches, oil on canvas (o/c 1266) Collection Springfield Art Museum, Mo, © Jon Schueler Estate