"Life changes in an instant." Wouldn't you know I'd be rereading Joan Didion's eloquent Year of Magical Thinking the day I picked up a phone message reporting the sudden death of artist Richard Lee on Martha's Vineyard? As I drove through heavy Monday-morning traffic about an hour later, a daunting SUV loomed up and passed. Its dusty rear window bore one of those florid memorial decals with the name of a loved one encircled by the phrase "some people dream of angels... I held one." If you knew my friend Richard you'd likely think, "Angel? - Nope. Ariel." A sprite fully capable of channeling an SUV driver to cut in front of me for a giggle.

Richard was born in 1933, about the time male actors started taking the part of Ariel in Shakespeare's Tempest, a character played by females for the previous 300 years. His own elfin existence encompassed roles as dancer, mask-maker, restaurateur, painter. Richard introduced his reverse glass pictures at a Beverly Hills exhibition in 1965. Shows in Munich, Paris and Los Angeles followed. A 12-year journey eventually led him from California to Martha's Vineyard -- via Europe, Hawaii, and Colorado. By then his obsessive technique and imaginative visual vocabulary were well established. Just shy of 80, he was still slight, silvery quick, worldly wise. He used to tease people by telling them that Hieronymus Bosch -- the 15th-century Dutch painter of strange and wondrous fantasies -- was his grandfather. We'd just begun working towards a retrospective of his work, and I thought we had all the time in the world.

Well, we do if you look at the beings generously scattered across the front of Sinking and Burning, a curious cabinet with inset reverse glass paintings now in the museum's collection.

The process of reverse glass painting dates back to thirteenth-century Italy, but Richard's recondite mixture of motifs, culled across centuries and cultures, is distilled into a unique parallel universe populated by all manner of mythological, hieratical and chimerical creatures, a world that leaves much to the viewer's own imagination. Dreamlike, the cabinet is filled with visualized noise, humming with life despite the rather dire title drawn from the Italianate composite towers at the bottom of the composition. As one tower subsides into azure waters, the other's foundation is ablaze.

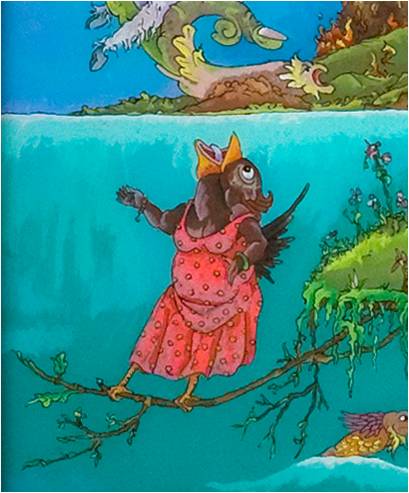

In Sinking and Burning, a mask inspired by Oceanic art dominates the top of each arched panel. An oculus pierced through the forehead of the purple mask reveals a glimpse of a distant island in a watery expanse. A muscular kahuna, endowed with magical powers, emerges from a ring of fire atop the blue mask. He, like fire itself, is a purifier. And water not only drowns; it gives life. Luxuriant downward trailing vines and flowers bracket the masks. Chief among them are strange blossoms echoing beach rose, morning glory, trumpet vine -- all known for indefatigable, even invasive growth habits. A golden nimbus sets off the pale visage of a male saint borne up by a flying fish, while a female flower spirit emerges from a vigorous stalk that miraculously produces hybrid parrot fish as well as somewhat noxious blooms. Assorted grotesques occupy heaven and earth. Meanwhile, a blackbird in a red coat with white collar and cuffs has gone out on a limb with his lute.

He sings earnestly across the waters to his lady bird.

Perched precariously in her pink gown, she, too, warbles the song we cannot hear. A threnody? Cool jazz? "O Solo Mio"?

Like Lee's imagery, the case piece housing the twinned glass panels marries old and new. The boxy walnut Eastlake-style storage unit is a thrift-shop find that was likely on-island by the 1880s. Poised on claw-and-ball feet, new faux-grained Chippendale cabriole legs lift the bulky case aloft, countering the downward movement of the panels with their heady decoration. Formal choices strike a balance between painting and furniture, mitigating the sense of incipient chaos. Somehow, the Renaissance-inspired baptism taking place in the lower right-hand corner seems reassuring, even if the devotee's hair is on fire and he is closely observed by a squatting Caliban-like monster.

We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live. That's Joan Didion's 2006 compendium of early non-fiction, rich with elegant articulation, implied angst. Similarly, despite a vivid palette, Richard Lee's beautifully drawn characters are chilly, refined in a glass alembic. The artist's technique provides an eerie, even gloss -- he applied pigments to the backs of glass panels, through which we look as if peering through a sheet of ice. That each picture was created quite literally backwards -- with details applied to the glass before the main figures and then the background were added -- reifies the surreal subject matter.

A lucid sense of performance spotlights the artist's power -- his work can be at once engaging, repellant, majestic, mundane, amusing, disturbing, inspiring, mystifying, inclusive, and self-referential. On a remote island like Martha's Vineyard, anything useful is unlikely to be thrown away. The artist's act of salvage (unwanted cabinetry rescued from the junk store) becomes his message of salvation -- trash transformed by the hand of the painter. Lee didn't take the basics for granted. Earth, air, water, and fire -- the four archetypal elements of the ancient world -- are all celebrated here.

So are arhats, enlightened beings who battle negative forces on their path to nirvana. Seconds after I dodged the SUV I saw one. I'd first encountered this character on another of Richard's cabinets -- a black man wearing lime green jeans and pink cowboy boots, honoring the Buffalo Soldiers who helped settle the American West. This time, on a Baltimore street corner, he sported flowing bleached blonde locks cut General Custer style, topped with a debonair cowboy hat. He was completely dressed in white. In Western countries, white -- the opposite of black -- is the color for brides, celebration, new born innocence. In the East, white is the color for mourning. Angels are said to wear white. Sprites wear whatever they like. Those are some of the stories I'm currently telling myself.

Richard Lee

Sinking and Burning, 2005

Walnut, faux grain paint, parcel gilding, reverse painted glass

69 x 44 x 14 inches

The Baltimore Museum of Art. Purchased in Honor of Alexander Baer's Birthday with funds contributed by his Friends; and Lilian Sarah Greif Bequest Fund, 2010.58