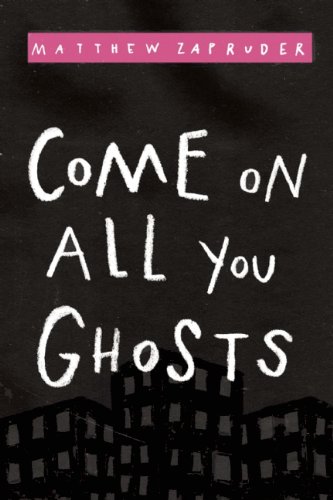

Matthew Zapruder is one of the Bay Area's most interesting poets. He and I recently had an interesting conversation about poetry, poetic craft, and the reader. Zapruder is the author of three collections of poetry. His most recent book, Come On All You Ghosts (Copper Canyon, 2010), was selected as one of the year's top five poetry books by Publishers Weekly, as well as the 2010 Booklist Editors' Choice for poetry, and the 2010 Northern California Independent Booksellers Association poetry book of the year. He is also an editor at Wave Books and the recipient of a 2011 Guggenheim Fellowship. Zapruder teaches in the low-residency creative writing program at UCR-Palm Desert. He lives in San Francisco.

Dean Rader: I'm going to begin with a confession -- I've always been a little obsessed with genre. And, recently, I've been thinking a lot about the relationship between genre and readership. You're someone who writes a lot of different kinds of things, and you've done graduate work in various disciplines. You're also a publisher. So, why poetry? What draws you to poetry despite its historically small readership? Do you feel like you are committed to poetry as a project, or are these books of poems just a slow buildup to your tell-it-all memoir?

Matthew Zapruder: When I first started writing, in my early 20's, I didn't know what sort of writing I wanted to do. I just had the urge to write something. When I sat down and worked, what came out was not stories, or essays, or songs, or a novel, but poems. This was a great and pleasant surprise. At that time I was studying Russian poetry (in the Ph.D. program in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Berkeley), but also other great Russian writing, so it could have turned out a different way. Thankfully it didn't. I think the simplest answer to your question of why I write poetry, is because when I do I am led to say (and understand) things I could not in any other way. These spaces of contradiction and mystery and strangeness among our ordinary uses of words that I discover when writing poetry seem absolutely essential to me. When I want to do something else with language -- such as make an argument, or explore a certain issue -- I usually will write an essay. What about you? What first got you writing poetry?

Rader: As an undergraduate, I took a standard American literature survey course. One of our assignments was to sort of poke around in a poetry anthology (I still have it, by the way, Diyanni, Modern American Poets: Their Voices and Visions) and see if anything grabbed us. Randomly, I stumbled on to some W. S. Merwin and James Wright poems. Merwin was on one side, Wright on the other. I had never read poetry like that before. I thought if that kind of stuff was out there in the world that I didn't know about, what else might be out there? So, I was drawn to writing poetry because I wanted to make on the writer's end what I had experienced on the reader's end. It was mostly about language.

Where do you think you find the language for your poems? What do you want that language to do and be?

Zapruder: I think a misconception some people can have about poets is that they are mainly interested in "language" as pure material, as something outside of its function as a communicative mechanism. Maybe this is because at least on the surface some poems seem uninterested in a reader. I am very interested in the reader, in fact there is probably nothing I am more interested in.

It is not exactly a breakthrough in cultural criticism to point out that nowadays our world is filling itself up more and more with distractions that take us out of the moment and into other spaces. I write poems to take myself out of that distracted, half aware, limited space, which I am just as susceptible to as anyone else. And when I find the "door" it comes in the form of some sentences that I, and also anyone else who picks up the poem, can read and understand and feel something deeper and stranger and more mysterious and more real.

Often people are surprised by the fact that I speak in a regular way in my poems, even if the order of what I am saying or the ideas are unfamiliar. Did you feel as a beginning poet, or a student of poetry, that it was somehow not "poetic" enough to write in conversational language? Also, I'm curious what your students said they did like about poetry?

Rader: Well, obviously, my students cited poetry's impressive track record placing recent graduates in high-paying jobs... Actually, most said they like poetry's "emotion." Some said they enjoyed having a personal connection with individual poems, and they appreciated being able to relate to a feeling or idea. For them, it was really important to be able to connect with the poem on an emotional (and sometimes intellectual) level. Some said they liked how poetry made them see things in a new way, and one or two mentioned how poetry can be "beautiful," which is in part a nod to language, but literally no one specifically talked about what we would call "poetic language."

My ear loves sounds made with words, and in a few of the poems from Works & Days, I intentionally focus on the marriage of the rhythmic and the sonic. I think these poems stand out in the collection -- good or bad -- because, as you note, the rest of the book is written in a pretty conversational tone. Hopefully, the poems are both accessible and smart, intellectually engaging but funny.

You do a nice job of this. I have been especially intrigued by how you begin your books. The first poem from Come On All You Ghosts, "Erstwhile Harbinger Auspices" does similar work though more subtly. It is a really generous entrée to the reader. We've had a conversation before about wanting our books to love the reader, and I'm wondering how you go about ensuring that happens.

Zapruder: I agree with your students. I think I like the same things about poetry that they do. It gets back to the function of poetry, which is for me (both when I write it and when I read it) to create, or make me aware of, the sorts of vital experiences and feelings that are so often crushed by the various mechanisms of our lives.

Rader: Let me ask you one last question. What is the one thing you want for contemporary poetry? What would you like it to do that it is not presently doing?

Zapruder: I like your question a lot, though it seems like a big thing to me to hope for something for "contemporary poetry." So my initial reaction is to say, I hope for many things for my own poetry: honesty, directness, and a sense in whatever readers might come to it that I am trying to articulate the elusive feelings, fears, experiences that are all part of the natural condition of being alive in this weird, awkward, scary, amazing time. And I hope to find those things when I read the poems of my contemporaries, and often do.

As for contemporary poetry, I guess I would come back to something we were talking about earlier in this interview. I wish for contemporary American poetry that the poets keep the reader more in mind: that poets continue to find various and authentic ways of thinking about who might read their poems and why. I don't mean in order to present the poems as a "product" or accessory to a cultured or hipster lifestyle (poetry should never try to be cool, that's just embarrassing, it's like when a dad tries to be friends with his kid's friends). And I don't mean that poems should always be about familiar or common experiences. I mean that readers should be able to feel in poetry today a genuine and generous strangeness, a reaching out, a desire on the part of the poem itself (as odd as that may seem to say, it is how it feels to me when I read poems, that I am having an experience with the poem itself) to make contact and increase the actuality of imagined spaces.