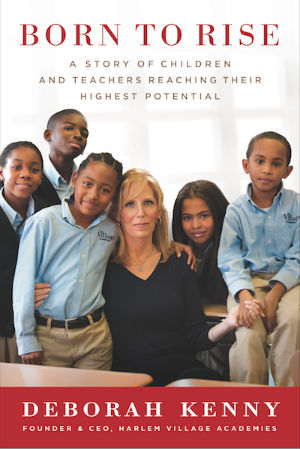

The following is excerpted from "Born to Rise: A Story of Children and Teachers Reaching Their Highest Potential," available now from Harper.

CHAPTER FOUR: PROVIDENCE

Teachers were the answer. Though I hadn't worked out the details, I was sure the only way to fix education was to focus on people -- the teachers -- to cultivate their passion and tap into their talent.

The question was how.

How to give every child in America an excellent teacher? I would be obsessed by this

question for the next ten years.

I'd been thinking about how to change the system, how to eradicate educational inequity. I'd

read dozens of books, met with experts, and learned a lot from listening to teachers. Finally I'd

developed at least a basic strategy: Instead of creating the ideal school design as a product to be replicated by teachers, we needed to design schools for teachers, schools that would support teachers, and enable them to do their best work and bring out their highest potential.

But I wouldn't accomplish anything by just thinking and talking and reading. I had to do it --

to get into the trenches and challenge the current system by starting a school system of my own.

That was my dream.

The reality was that my "people, not product" strategy wouldn't pay the bills. Joel hadn't had

life insurance -- who thinks of these things when you're young? All I had was a small savings

account. It could sustain me and my three children for about six months, but it was for emergency use only. I was never supposed to touch it.

So I had no real plan and barely any money. The one thing I did have was a firm sense of

commitment. I was committed for the sake of Christopher, stuck in the failing school in East St.

Louis; I was committed for Eric Boyd, trapped in the housing project in Chicago. And I was

committed for the mothers and children I had met in Yonkers, the South Bronx, and Harlem.

Back in my first month of college, I'd copied down a quote in my journal about commitment

and providence. I had read it many times. So I opened my journal now to reread it again:

The moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one's favor all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamed would have come his way. Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it.

Commitment. Providence. This was it. I would use my savings to start a system of schools, to

work on the front lines of reform. Somehow I'd figure it out. I was all in.

I called my friend Sharon to tell her that I was leaving Edison to start schools in Harlem with

my emergency savings. "We need to talk," she said. "I'm calling everyone. Meet us at California

Pizza Kitchen at eight."

We'd barely sat down when Sharon spoke up. "Look," she said, "one thing you've never

been is normal." Everyone laughed, but she hushed them. "Seriously. What are you going to do when

you run out of money? I mean, we love you, but you're not thinking clearly. It's not the right time in

your life. You have no security."

"What's the worst that could happen?" I said. "If I fail and run out of money, I'll just pitch a

tent in my parents' backyard!""You can joke about it," Jeff said, "but what will happen when you do run out of money?

You have a mortgage. Didn't it take you ten years to pay off your student loans? Aren't you afraid

you could lose your house?"

"The only thing that scares me," I told them, "is how depressed I will be if I don't do this."

The food arrived, but nobody paid attention. They were all staring at me. "Do you even have

any idea what you're doing or how to go about doing it?"

"No," I admitted, "but I have to try."

"So how about starting slowly," Sharon suggested. "You could volunteer at that new

mothers' training program you visited in Harlem."

"And what about your wardrobe, your vacations, the kids' music lessons? I mean, everything

is going to be different. Why do you always have to be so damn radical? Are you seriously ready to

change your lifestyle?" asked Jeff.

"Actually I've thought about that already," I said. "There are about seven or eight things I

have to give up and I'm willing to do it. I've made a list, and -- "

"Of course she has," interrupted Becky, as everyone laughed.

And on it went. By the time dessert arrived, everyone had agreed my plan was a bad idea.

While the others were devouring the brownies and ice cream, Larry sat silently, drinking his coffee.

Finally he said, "It's noble that you want to use your life to serve others. We just want you to be

realistic."

But they didn't get it. I wasn't being noble. I had to do this. I felt like I would die if I didn't.

The next morning was back to reality. Up at 6 a.m. to make breakfast, sign permission slips,

put school lunches into backpacks, and get Avi, Rachel, and Chava onto the school bus.

Once the kids were out the door, I decided to set up an office to convince myself that my idea

was more than a pipe dream. I cleared away board games, tennis racquets, and other equipment from

the corner of a small playroom in our basement. I dragged over a light gray laminated desk I had

bought the prior year for twenty-two dollars at a garage sale. I added a navy blue chair, a f limsy

bookshelf, a file cabinet, and a computer and printer. Then I called Verizon to schedule installation of

a phone line in the basement. (Those were the days of dial-up AOL.) My work attire was sweatpants

and an old T-shirt.

I sat down at the desk and took out a notepad. On top I wrote "School Start-Up." Then I

underlined it. Twice.

How do you start something from nothing? I asked myself as my mind wandered. I found

myself staring at the rust on the filing cabinet. Then I became distracted by listening intently to lawn

mowers outside the basement window. Time to relocate.

Our family room had always been my favorite. The walls were lined with bookshelves, and

the large windows had a view of the woods in the backyard. I thought about Joel, but then forced the

thought out of my head. I couldn't allow myself to fall backward into sorrow.

Okay, just think, I told myself. What should be my first step? I wrote the number 1 and

circled it. I wanted to write out a long list but I couldn't come up with anything. So I put down the

notepad on the coffee table, and went into the kitchen to make some tea.

Ten minutes later I was back on the couch and back to the notepad, steaming mug in hand. I

picked up my pen and made a box around the words "school start-up." I made a second box around

the words. I drew a little stick figure on the top right corner of the paper. Then I labeled him

Christopher, and gave him five little stick figure friends.

I looked out the window, then at a painting Joel had made for me while he was in the

hospital, and then back at the lined paper. I looked at the pile I had gathered on the coffee table.

There were lots of papers and books, and notepads filled with my ideas. I had a strategy: people, not

product. Why couldn't I get moving?I had no idea how to begin. What I needed was an actionable task list. But I didn't really

know what I was doing. Was this even possible? Maybe my friends were right. Maybe this whole

thing was as ridiculous as it sounded. I was lonely and I missed Joel.

The kids would be home from school in two hours and my approach was clearly going

nowhere. So I put down the empty pad, laced up my sneakers, and went out to run.

As I was running, I gave myself a Nike-inspired pep talk: Just Do It. Don't look back. Keep

moving forward. I told myself to figure out the two or three top priorities and focus on them like a

laser. I pounded the pavement. Halfway up a killer hill, it hit me: funding. Seed money was the most

important thing I'd need to begin. Without it, nothing would get off the ground. The second priority

would be applying for charters. No money, no charters equals no schools. It had taken me half a day

to realize the incredibly obvious.

I sprinted for the last minute to the house, pushed the door open, threw off my sneakers, and

ran into the family room. I grabbed the pad and pen, ran downstairs to my new office, and sat at the

desk. I tore off the first page and started fresh. On the top of one page I wrote "Funding" and on top of a second I wrote "Charters."

Reprinted from "Born to Rise" by Deborah Kenny. Copyright © 2012 by Deborah Kenny. With the permission of the publisher, Harper.