By and large, how Americans got their news when I first met, got to know and was privileged to work with the CBS News legend, Edward R. Murrow in 1948 was by reading newspapers. Listening to the radio took second place and watching television news was "so so" at best.

Although broadcasters like Edward R. Murrow, H.V. Kaltenborn, Gabriel Heatter and Lowell Thomas had become big names in America, newspapers like The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Baltimore Sun, The Atlanta Constitution, The Boston Globe, The Chicago Tribune, The Denver Post, The Los Angeles Times and the San Francisco Chronicle were where it was at — until the truck drivers delivering their newspapers to newsstands in those cities soon found themselves driving through neighborhoods, the rooftops of which were festooned with television antennas feeding what came to be known as commercials into the houses below (commercials paid for with money that once went into the coffers of newspapers) while, in the suburbs, kids on bicycles were tossing news papers they carried in a canvas bag slung over their shoulder up onto front porches on streets — under which cables carried commercials that gobbled up advertising dollars that had formerly been a source of income for newspapers. Along with that, broadcasters like Walter Cronkite, Mike Wallace, the late Ed Bradley, the late Chet Huntley, David Brinkley, Peter Jennings and most significantly...

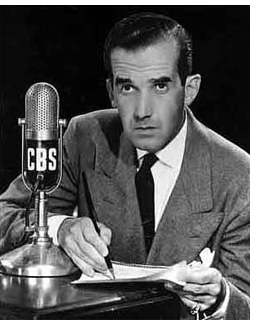

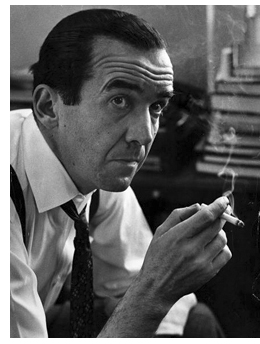

The late Edward R. Murrow,  the most respected name ever in broadcast journalism, were attracting attention — especially Murrow who with his movie-star good looks, could have been a matinee idol, but, fortunately for us and the world at large didn't. A keen mind and a way with words led him to radio and then to television where I was privileged to be associated with him as the director of his and Fred Friendly's winner of just about every award in broadcasting — "See It Now" — as well as producing and directing his year-end specials and his coverage, 56 years ago, of Queen Elizabeth's coronation...the kinescope of which (film recorded off the tube before video tape burst on the scene) was edited by the two of us during what was then an eleven-hour trip across the Atlantic on a chartered British Airways trans Atlantic propeller-driven airliner stripped of a couple of dozen or so of its seats and replaced with what were called "movieolas" to edit what were called "kinescopes" (film recorded by cameras focused on the screen) ready to be aired when we touched down in Boston. Why Boston? We were in a race with NBC to be the first on the air with footage of the Coronation and landing in Boston and airing it from the airport instead of from a studio, gave us a head start.

the most respected name ever in broadcast journalism, were attracting attention — especially Murrow who with his movie-star good looks, could have been a matinee idol, but, fortunately for us and the world at large didn't. A keen mind and a way with words led him to radio and then to television where I was privileged to be associated with him as the director of his and Fred Friendly's winner of just about every award in broadcasting — "See It Now" — as well as producing and directing his year-end specials and his coverage, 56 years ago, of Queen Elizabeth's coronation...the kinescope of which (film recorded off the tube before video tape burst on the scene) was edited by the two of us during what was then an eleven-hour trip across the Atlantic on a chartered British Airways trans Atlantic propeller-driven airliner stripped of a couple of dozen or so of its seats and replaced with what were called "movieolas" to edit what were called "kinescopes" (film recorded by cameras focused on the screen) ready to be aired when we touched down in Boston. Why Boston? We were in a race with NBC to be the first on the air with footage of the Coronation and landing in Boston and airing it from the airport instead of from a studio, gave us a head start.

That's how "horse and buggy" airing an event overseas the same day it took place was when television first burst on the scene — editing a kinescope (videotape was still a distant dream) — of an event of historic proportions on an airplane and airing it from an airport. Today, the lack of worthwhile programming — not looking for new and better ways to broadcast the existing programming — is the problem.

Today, the TV techs are virtual wizards at getting us on the air in a flash — even from the moon — which is nothing short of amazing. What is also "nothing short of amazing" is how much unadulterated drivel finds its way onto the tube.

Leave it to Murrow to say that without using television to teach, illuminate and inspire "it is nothing more than wires and lights in a box."

Anybody want to take issue with that? The first time I laid eyes on Ed Murrow I was a 21-year-old World War Two war correspondent — enthralled by the sights and sounds of wartime London, none more enthralling than the sight and sound of a broadcaster who every night left his sandbag-protected BBC studio, a short walk from his CBS office, climbed a flight of stairs to a rooftop overlooking the city to bring America a first hand account of the Luftwaffe's attempt to burn London to the ground.

There were, to be sure, newsreel pictures of what came to be known as "The London Blitz" but because it was before television, the only on-the-spot-as-it-was-happening pictures of it transmitted each night to the United States were those Murrow painted with words...and doing that — painting pictures with words — is a what good writing is all about.

That the television age was as good to him as the age of radio had been was hardly surprising.  He was, if anything, a casting director's dream come true. If someone who had never seen him on television — only heard him on radio — had undertaken to do a docudrama about him and he showed up under an assumed name to audition for the part, he'd have gotten it. Ed Murrow looked like Ed Murrow, just as Walter Cronkite looks like Walter Cronkite. Think about it: who else could they be? In an age of Amos and Andy, Kate Smith and Bing Crosby, how did an academic with a penchant for humanitarian causes become a broadcasting icon? When the FCC required that broadcasters perform some sort of public service, CBS, NBC and ABC started news divisions...and it wasn't long before Bill Paley's Midas touch led him to make Murrow the trademark of his news division, not long, either before a simple phrase like "Good Night and Good luck" became as familiar to a generation of radio listeners as Clark Gables' "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn" was to a generation of movie goers.

He was, if anything, a casting director's dream come true. If someone who had never seen him on television — only heard him on radio — had undertaken to do a docudrama about him and he showed up under an assumed name to audition for the part, he'd have gotten it. Ed Murrow looked like Ed Murrow, just as Walter Cronkite looks like Walter Cronkite. Think about it: who else could they be? In an age of Amos and Andy, Kate Smith and Bing Crosby, how did an academic with a penchant for humanitarian causes become a broadcasting icon? When the FCC required that broadcasters perform some sort of public service, CBS, NBC and ABC started news divisions...and it wasn't long before Bill Paley's Midas touch led him to make Murrow the trademark of his news division, not long, either before a simple phrase like "Good Night and Good luck" became as familiar to a generation of radio listeners as Clark Gables' "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn" was to a generation of movie goers.

But, despite his close, personal relationship with CBS' chairman, Bill Paley, Murrow knew that continuing to be a success in broadcasting meant — as it does everywhere in broadcasting — doing something for your boss' pocketbook as well as his soul. Having already done that with his "This is London" broadcasts (which, rumor had it, were regularly listened to at both 10 Downing Street and 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue) and later with his and Fred Friendly's highly regarded radio series "I Can Hear It Now," he and Friendly were ready to take the plunge into television with "See It Now" — a remarkable series of Sunday afternoon broadcasts, the most memorable of which took on the dreaded Junior Senator from Wisconsin, Joe McCarthy, who took time out from looking for communists and communist sympathizers to respond as follows:

"Now, ordinarily, I wouldn't take time out from the important work at hand to answer Murrow, However, in this case, I feel justified in doing so because Murrow is a symbol, the leader and the cleverest of the jackal pack which is always at the throat of anyone who dares to expose individual Communists and traitors." Murrow's response was "The actions of the junior senator from Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay amongst our allies abroad and given considerable comfort to our enemies — and whose fault is that?

Not really his. He merely exploited it and rather successfully. Cassius was right. The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars but in ourselves. Good night and good luck."

Later on — on his own, without Friendly (a journalistic purist, if there ever was one), Murrow embarked on yet another broadcast for his and Bill Paley's pocketbook with an interview show called "Person to Person"...not exactly the best use of an Edward R. Murrow...as noted by the television critic John Crosby who called the two broadcasts — See It Now and Person to Person — "high Murrow and low Murrow" — two broadcasts that, in essence, sparked me to come up with 60 MINUTES.

"High Murrow and low Murrow" in the same broadcast predicated on the same rationale that Murrow built his "Person to Person" on ....that it's okay to look in Marilyn Monroe's closet if you're also willing to look into Robert Oppenheimer's laboratory. About that band of brothers who came to be know as "Murrow's Boys" — among them Eric Sevareid, Howard K. Smith, and Charles Collingwood — the best known of a dozen or so first rate reporters who could hold their own with anybody and who I liked to think of as characters in a story that supposedly happened in the last Century about something or other of a newsworthy nature at The Vanderbilt Mansion on New York's Fifth Avenue...

When the butler, so the story goes, went into the drawing room he announced to Mrs. Vanderbilt that there were, "a dozen or so reporters at the door and a gentleman from The Herald." Had Murrow been around in those days and one of what were known as "Murrow's Boys" had been among the reporters at Mrs. Vanderbilt's door, it is not unreasonable to think the butler might very well have added "and a gentleman representing Mr. Murrow."

Is it different now? Not all that different. Murrow and Friendly gave us something to measure up to. And, by and large, broadcasting has measured up. One of the things that's different now is that being a television journalist (or a print journalist, for that matter) is a better way to earn a living than it used to be. Guys who were known as "ink-stained wretches" when I started out...now have weekend houses and kids in private school and more and more of the best reporters and editors are — at long last — women who have the same determination to cover a story without fear or favor as the best of their predecessors did, even though not one of them ever made the Murrow team. Over and above the first-rate reporting that made the Murrow Boys (not one Murrow girl in the bunch) stand out was a kind of quirkiness that enhanced rather than detracted from their stories.

Take Murrow's longtime colleague Eric Sevareid, who always seemed to be deep in thought like the day I dropped in on him and sensed I was intruding on some weighty matter he had been turning over in his mind. How did I know? He shared it with me.

"Have you noticed?" he said, "that the messages in fortune cookies are not being written as well as they used to be?" Was he putting me on? No, bad writing was an anathema to Sevareid, even when it showed up in a fortune cookie, while Murrow, who, I'm reasonably sure, never brooded about fortune cookies, had a sense of humor about himself that was more delicious than a fortune cookie...as in his hearing through the grapevine that a bunch of his colleagues were starting a club called "Murrow Isn't God," and asking, "Where do I go to join?" But my favorite story about him is one he loved to tell about Israel's Moshe Dayan driving him to an air strip in the Negev and telling him how much he admired him for his wartime "This is London" broadcasts...his putting the skids to Joe McCarthy...his ground breaking television coverage of Christmas in Korea...to which Murrow responded that he had gotten far too much of the credit for those broadcasts, that the guys who deserved it were guys he worked with who went out of their way to make him look good...

At that, Dayan clammed up and never said another word until Murrow was boarding the plane...and shouted up to him from the tarmac: "Murrow! Don't be so modest; you're not that good!"

However, even that didn't top Bill Downs, one of the Murrow Boys, reporting from one of the two inaugural balls in Washington on the eve of Jack Kennedy being sworn into office that: "Both the President's balls are in full swing tonight." Did he get chewed out? No, everyone was so convulsed with laughter that had they"chewed him out" they might have choked.

So much for Ed Murrow and his "Murrow Boys." Where we're going to find another bunch like them is beyond me. For that matter, where we're going to find another Walter Cronkite, another Mike Wallace, another Ed Bradley — to mention just a few of the giants of broadcast journalism I was privileged to work with over a long and rewarding career in the news business — is also beyond me.