More than 2,000 pieces of Ernest Hemingway memorabilia went digital at the JFK Presidential Library in Boston today -- everything from personalized (but unused) airmail stationery to pre-World War I notebooks and multiple passports, and everything in between. It's not that we don't already know almost everything about the man and the writer -- now we know that he didn't throw anything away!

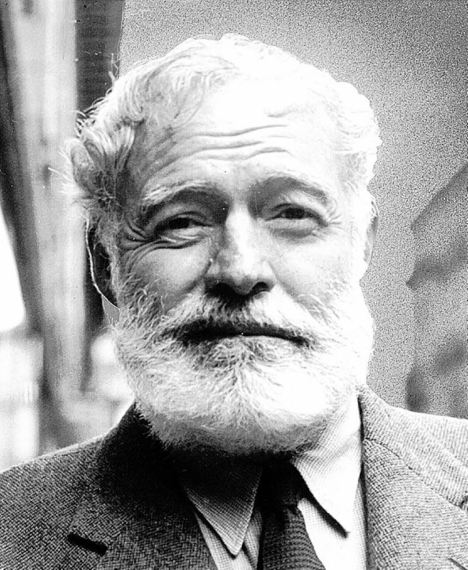

None of that matters, really, as the Hemingway legacy lives on regardless. Like many of my male baby boom cohorts, the Hemingway hero, the Hemingway style and the Hemingway ethos cast a very large shadow over us. Back then, the world belonged to us men (or so we believed) and there was nothing more masculine and manly than Ernest Hemingway.

And while much of that has been debunked and dispelled over the ensuing years, some effects still linger. Chief among these are writing style (brevity) and the Hemingway hero. The former is well summarized in the latest collection by none other than the man himself -- "You can remove words that are unnecessary and tighten your prose," he writes, a sentiment that Strunk and White of The Elements of Style fame would wholeheartedly endorse. Less was more, and Hemingway's prose became the gold standard for us would-be writers.

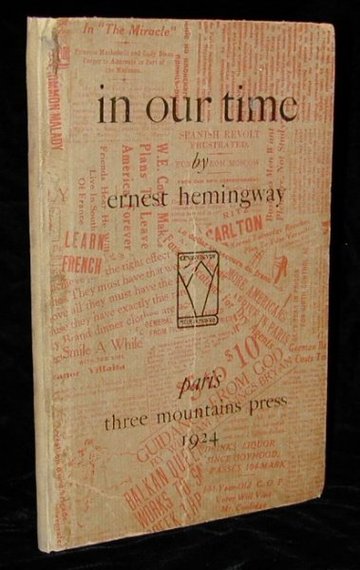

The hero part was a lot more complicated, mainly because of Papa's own suicide. I can remember hearing the news on the radio in July 1961, and rehearing it throughout high school, college and graduate school as I read and re-read A Farewell to Arms, The Sun Also Rises and In Our Time. It was hard to reconcile the Hemingway persona with the reality, and I recall endless late-night discussions about whether suicide was the ultimate heroic, or cowardly, act. I'm still wrestling with that conundrum, as I'm guessing maybe Hemingway himself did, up until the moment he pulled the trigger.

And I wonder, all these years later, just why I used his brilliant collection of World War I short stories and "vignettes" within In Our Time as the basis for my own insights on my war in DEROS Vietnam.

Was it the succinctness, the directness, the violence of In Our Time? The Hemingway hero as personified by Nick Adams? The code of masculinity?

Or was it something else? The truth about war and warriors and PTSD? Thanks to Hemingway, I was able to use writing as a way to try and figure all this out. And, like most veterans, I'm still trying.

It's possible Ernest Hemingway never figured this out either, which may explain why he kept writing and drinking and fighting and wandering. His family's penchant for depression and suicide notwithstanding, Hemingway and his "hero" look an awful lot like many veterans I know. And like him, and them, many of us are still trying to get our feet on solid ground, are still trying to make it back home.

That's something else the digital collection shows us -- even after his abrupt departure from Cuba, Hemingway sure as hell expected to return home -- a Glen Miller album still nestled in the Hi Fi, his shoes were right by the door.