The rue des Martyrs is only half a mile long, but for me there is no better street in Paris. Northeast of the place de l'Opéra, half a mile south of the Sacré-Coeur Basilica, it packs nearly two hundred small shops, restaurants, and cafes into its storefronts. On this street, the patron saint of France was beheaded and the Jesuits took their first vows; François Truffaut filmed scenes from The 400 Blows and Pharrell Williams and Kanye West came to record at a new-age music studio.

I discovered the rue des Martyrs shortly after my husband, Andy, and I moved to Paris with our two daughters, in 2002. The street became my go-to place on Sunday mornings, when its shops are open while much of Paris is shut tight. It took me nearly a decade to move into the neighborhood. I wandered up and down the street at odd hours of the day and night. The street is all about sharing, and I bonded with its merchants, artisans, and residents. Paris finally felt like home. And thanks to this street of magic, anyone can feel at home here.

___________

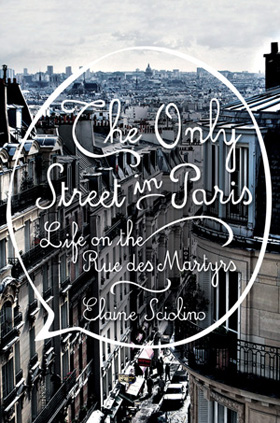

What follows is adapted from "Le Potluck," a chapter in The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue de Martyrs, to be published November 2 by W. W. Norton & Co. Copyright @ 2015 by Elaine Sciolino. The book available at W. W. Norton, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Apple, and Google Play.

***

Over time, I got to know so many people on the rue des Martyrs that I wanted to bring them together in a celebration of the street--the whole street. But how to do it?

Sébastien! I thought. Sébastien Guénard, the chef and owner of the bistro Miroir, at the top of the rue des Martyrs.

"Imagine a party where everyone comes together," I said. "The people at the bottom meet the people at the top."

"Let's have the party here!" he said.

Miroir used to be a Montmartre joint catering to tourists who craved cheap onion soup and garlicky escargots. Although the place looked filthy and run-down when Sébastien first saw it, it was a coup de foudre--love at first sight. "There was a side to the place that said, 'So Paris, the Paris I love, the Paris for real people,'" he recalled.

He opened Miroir in 2008 with financial backing from a businessman with a passion for reviving this part of Paris. Every morning, neighborhood residents stop in for coffee and conversation. The postman comes by, with the mail, of course, but also for a quick espresso; if he is unable to deliver a package to one of the neighbors, he leaves it at Miroir for safekeeping. Because the school nearby bans skateboards, students sometimes leave them with Sébastien until classes let out. Most afternoons, before the restaurant opens for dinner, Sébastien stands on the sidewalk, greeting everyone he knows with double-cheek kisses. Every evening, he sets aside three or four tables for friends and regulars who might show up.

Early some mornings, I venture up to this part of the rue des Martyrs. I perch at a table close to the window and watch the world go by. Catherine Mourrier, a slip of a young woman who chain-smokes and sports a brush cut with her bangs gelled upward, makes me a café crème in between washing down the sidewalks and Windexing the windows. She always brings me a small pitcher of extra-hot milk. One day she started serving me croissants.

A man who lives at the top of the street is a different kind of regular. In the old days you would have called him a wino. He carries a guitar on one shoulder and sings when the spirit moves him. He came by one morning and asked Sébastien to open his wine shop, across the street, because he wanted a bottle of red called "Forbidden Fruit." If Sébastien was annoyed, he didn't show it. He unlocked the shop door and handed the man a bottle. The man didn't pay.

"Who was that?" I asked, after he had left.

"An artist of the neighborhood," Sébastien said. "He's as sweet as can be."

"But he didn't pay you!"

"Oh, he'll pay one week or the next."

***

My idea for a party may have seemed whimsical, but I was determined. First, I mentioned it to everyone I knew on the street. Then I hand-delivered invitations. "Dear Martyrians," it began. "The moment I have talked about so much has finally come!" I invited them "to celebrate our rue des Martyrs, which we love so much."

I planned an old-fashioned American potluck dinner. Potluck does not exist in Paris. The French would be unhinged by its disorder: no quality (or quantity) control, no logic to the courses. Even a French family picnic in the country is more formal than an American potluck. To help bring people around, I included a note with the invitation, defining potluck as "a meal in which everyone brings something to eat or drink that can be shared. We do it often in the United States, because it's a great way to meet people around a simple meal."

We needed music, of course. I asked Pablo Veguilla, a young Puerto Rican-American opera tenor who lives just outside Paris, to join us. Pablo is an American success story. He was born poor in Chicago and raised in Orlando, Florida, where his father worked as a nursing home janitor and his mother as a hospital secretary. Yale University plucked him out of oblivion to study music at its graduate school, all expenses paid.

I suggested that he sing an aria from Puccini's La Bohème because of the opera's historical connection to the Brasserie des Martyrs, the famous nineteenth-century tavern at the bottom of the street. I told him that Henri Murger, whose book about Paris bohemian life had inspired Puccini, had been a regular there.

"Wonderful! Wonderful!" said Pablo. "I'm getting excited."

Most of the shopkeepers I invited shared Pablo's enthusiasm. Arnaud Delmontel, the baker and pastry chef, said he'd bring his signature loaf cakes. His competitor, another Sébastien (Sébastien Gaudard), an even more haute couture baker, promised a surprise. Éric Vandenberghe, the owner of the Corsican food shop, said he'd bring charcuterie. Yves and Annick Chataigner, the cheesemongers, offered Camembert and Beaufort.

I sweet-talked Justine, the daughter of the fishmonger whose shop, La Poissonerie Bleue, had closed more than a year before. By this time, Justine knew I was working on a book about the rue des Martyrs. "I am writing this book because of fish," I said. "If it weren't for you and your family's fish store, there wouldn't be a book. You are now the only representative of your family on the rue des Martyrs. Make them proud!"

(Excerpt continues below.)

I knew I had won her over when she sent me a text message asking what to wear.

My friend Amélie Blanckaert, who lives in a house on the rue des Martyrs, called on party day to say she couldn't come. She didn't have a babysitter for her two boys, aged four and two.

"I'll be there in spirit."

"What time do the boys go to sleep?"

"Oh, nine, nine-thirty."

"Bring them! We'll feed them!"

She said she would.

On party day, I still had not decided what to wear. "No black," my daughter Gabriela said. "Be festive."

I considered red, but Gabriela, who was the designated photographer, nixed that as well. "The walls and banquettes are red, and you would fade into the background," she pointed out.

I decided on a silk print Diane von Furstenberg dress and high-heeled patent leather Louis Vuitton pumps. I had bought both items at Troc en Stock, the secondhand boutique just off the rue des Martyrs. I arrived early at Miroir, giddy and nervous. Sébastien was holding his one-year-old daughter, Automne, in his arms. Pablo, dressed in a black suit, white shirt, and his signature ponytail, was testing an entire sound system he had lugged with him on the hour-long train ride.

"I've got great background music!" he said. "How about Dean Martin?" He mimicked the liquid-smooth croon of the King of Cool. "C'est si bon. Lovers say that in France," he sang, then burst into laughter.

Amélie and her sons were the first to arrive; the boys ran around the bistro as if it were their private playground. Within thirty minutes, fifty people had turned up. Just about everyone brought a dish: the baker Sébastien Gaudard, with his Jack Russell terrier on a leash, came with a Saint-Honoré cake (with cream puffs and a mountain of cream) and a Mont-Blanc cake (with pureed chestnuts). He said he could stay for only a few minutes because it was Monday, and Monday was bookkeeping day; he lingered for two hours.

Laurence Gillery, the artisan who repairs barometers, and her mother, Colette, who came all the way from Nice, brought homemade cheese biscuits and a Mediterranean pizza topped with sardines. Makoto Ishii, the manager of the Henri Le Roux chocolate shop, brought a grand box of assorted chocolates and bags of salted caramels. Viggo Handeland, from the Belgian waffle shop, brought three kinds of Belgian cookies. Éric Vandenberghe delivered a three-foot-long platter of Corsican charcuterie. Justine had made a chocolate cake. Didier Chagnas, the retired caretaker at Notre-Dame-de-Lorette Church, had made chocolate mousse.

Thierry Cazaux, the neighborhood historian, brought six copies of his book on the rue des Martyrs. Reilley Dabbs, an American exchange student working with me, brought Oreos.

Sébastien Guénard, our host, had made dense meat terrines in large loaves. I brought three of my no-fail potluck salads: rice with tiny cubes of colorful raw vegetables, bow-tie pasta with cherry tomatoes and Pecorino Romano cheese, and curried lentils with golden raisins and pine nuts. On and on went the menu: quiches in different sizes, petits fours in different shapes, sweet and savory cakes.

Wine, lots of it, of course.

Oscar Boffy, the artistic director at the transvestite Cabaret Michou, gave Sébastien a Michou apron displaying an image of the cabaret's trademark--the red-lipsticked, long-lashed blond floozy. He gave me a much more precious gift: one of his paintings (he is a painter on the side).

Charmed chaos reigned. We mixed classes and professions: politician, worker, merchant, business executive, writer, artisan, lawyer, retiree, student, artist, and intellectual. Most guests had never socialized together before. Some wore dresses and business suits; others came in jeans.

Justine had abandoned the black-and-white uniform of the butcher shop, unpinned her bun, and donned colorful print pants, a matching shirt, and lipstick. Guy Lellouche, the antiques dealer, came in a crisply pressed shirt and velvet slacks, with a silk scarf wrapped twice around his neck and his gray hair dyed brown. Zygmunt Blazynsky, the caretaker at the crypt at the site of the beheading of Saint Denis, wore a long sheepskin coat that he never removed.

Christophe, the real estate agent, made friends with Viggo, the Belgian waffle guy; Jean-Michel, the Jewish Holocaust survivor, with Didier, the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette Church caretaker; Zygmunt from the crypt with Oscar from Michou.

Jacques Bravo, who had recently retired as the mayor of the Ninth Arrondissement, solemnly proclaimed that by coming to the Eighteenth he had entered foreign territory. "This is a historic moment!" he said. "I have come to Montmartre! I have even dared to come without my passport!"

We packed Miroir so full that Pablo had to perch behind the bar to find a place to set up his sound system. The crowd became silent as he began to sing. Passersby gathered outside to listen, and a few tried to push open the door, hoping to join the party.

Then I called for order. Without success. Finally, Oscar spoke up--in English--in his showman's voice: "Ladies and gentlemen! Please!"

I thanked the crowd for coming to celebrate our street. I told them how much living among them meant to me. "It is impossible for me to be sad on the rue des Martyrs, thanks to you," I said. "Today, I am living my 'French dream' with you. Of course I am American, of one hundred percent Sicilian descent. But I have to tell you a secret. My mother had blond hair and hazel eyes. Her parents emigrated from Sicily, but they came from...."

I hesitated for a second, and Didier Chagnas and Michel Güet both shouted, "Normandy!"

"We're the historian corner!" said Didier. (French schools teach that the Normans conquered southern Italy, including Sicily, in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.)

"So you see, I am really half French!" I said.

"So when are you getting French citizenship, Elaine?" Liliane Kempf called from the crowd.

Pablo led us in Neapolitan love songs and even a tarantella--in Sicilian dialect--before he moved to "Les chemins de l'amour" by Francis Poulenc and then the ultimate French crowd-pleaser, Edith Piaf's "La vie en rose."

At this point, Michel and Didier decided Pablo was just the person to raise money to help restore the crumbling Notre-Dame-de-Lorette Church. They proposed a fund-raiser with him as the star. (They couldn't pay him, of course.) "Maybe a Rossini gala?" they asked.

Pablo suggested Bizet's Carmen. He had done his homework and knew that Bizet had been baptized at the church. "Carmen brings in the bucks," he said.

(Excerpt continues below.)

Meanwhile, the potluck for fifty was creating a delightful mess at Miroir. Since no one had cut into Sébastien's terrines, I did it myself and served big moist cubes on thin paper napkins. Makoto asked why I hadn't brought out his chocolates, so I set aside the terrines and walked the chocolate box around the room.

By the time I started the raffle, the crowd was deep into food and conversation. I climbed onto a banquette and stood before my guests with odds and ends I had solicited from merchants and residents.

"Is it time for a striptease?" asked Guy Lellouche.

"Very funny," I replied. "Did you know that the modern striptease was invented across the street--at the cabaret Le Divan du Monde?"

Oscar won a small terra-cotta bell. When he rang it, it emitted a pure, light sound. Oscar is a Buddhist, and the sound pleased him.

Pauline Véron, deputy mayor of the Ninth Arrondissement, won a glass paperweight in the shape of an oversized cut amethyst.

"For the jewel of the rue des Martyrs!" I said as I gave it to her.

I picked up a sixteen-inch, hand-painted porcelain sculpture of Mozart as a young man. To everyone's and no one's surprise, our opera tenor, Pablo, won.

"Ah, it's not possible!" said Liliane Kempf, who had donated it.

"It's perfect!" said Didier.

(Okay, it was fixed.)

Enzo, Sébastien's teenage son, won four recycled books from Circul'Livre, the monthly free book exchange on the rue des Martyrs. Jean-Michel Rosenfeld, the retired official from the Jean-Jaurès Foundation, won a photograph of a South African landscape taken by my daughter Gabriela. And so it went, until the crowd lost interest and my voice turned hoarse.

As some guests left, others arrived, including the greengrocers Kamel and Abdelhamid. They brought bananas, apples, and grapes. "I came, Elaine!" said Kamel. He said it again, to make sure I fully appreciated his presence. "Someone asked me to go to a café tonight because I didn't work today, but for you, I came. For you!" Abdelhamid, his father-in-law, stood shyly next to him, smiling and nodding. It was the most touching moment of an emotional evening.

Two of the young fishmongers arrived, with bottles of sparkling white wine. At close to eleven p.m., the last guest, Raymond Lansoy, the editor of a monthly magazine on Montmartre, appeared. He brought a wine with the unappetizing name: Le Vin de Merde. Everyone thought that was very funny.

Pablo closed the evening with Puccini's "Sole e amore" (Sun and Love), a mattinata, or morning song, that first appeared in 1888. He said it was an inspiration for Puccini's La Bohème, and he sang:

"The sun joyfully taps at your windows;

Love very softly taps at your heart,

And they are both calling you."

Then it was over. I helped Pablo pack up his equipment. "What a great time," he said. "Someone said to me--it was one of the fish guys--that tonight was the first time he ever heard an opera singer. People who didn't know me wanted to talk. People kept saying, 'Let me fix you a plate of food.'

"When you perform onstage, you never see the faces of your audience. Here I was two feet away from the crowd. I could see their reactions. I could hear them humming along. But you know what? People were having such a good time, they didn't need our entertainment to carry the evening."

We lingered, even though it was a Monday night. I stood at the door of the bistro with Sébastien. The evening had been a bigger success than we could have imagined.

"The crazy thing is that everyone came," he said. "People were happy to be here, they were happy to come for the rue des Martyrs. Everyone got involved; everyone brought something, a little present, something to eat.

"And then Pablo! People passing by on the street were amazed to hear an opera singer warming up his voice in a bistro at six p.m. You don't expect to hear an opera singer in a bistro in Montmartre!"

Sébastien was surprised that the informal chaos of the evening had worked so well.

"I'm going to say something awful," he said. "I think we all expected something very American."

"Meaning what?"

"In French people's heads, when you say 'very American,' it's all about the show, the appearance. The people who came tonight know you, so they also know that's not true. But I think they were expecting something much more showoffy, much more bling-bling. But it wasn't at all."

"But, Sébastien, you made it happen!" I said.

"An American party organized by an American in France for French people, with a Puerto Rican-American tenor who sang in Italian," he said. "It was out of this world. You know what I mean? You know what I mean? We had the American melting pot on the rue des Martyrs."

His praise was over the top, but I didn't quarrel with him. When I first came to live in Paris, in 2002, I had hoped to shed my American skin, to become more French. I was set on speaking flawless French with the smoky voice of the actress Jeanne Moreau and on dressing with the insouciance of the perfect Parisienne, Inès de la Fressange. I tried hard to fit in with the rhythm of my former neighborhood off the rue du Bac, in the Seventh Arrondissement, where refinement, restraint, and politesse reigned. It didn't happen. There were just too many codes to master, and the effort that went into it--which should always be invisible--showed through.

On the rue des Martyrs, the codes don't matter. I am embraced because of--not despite--the absence of a glossy French veneer. Authenticity--my identity as an American with deep roots in a foreign land--trumps pedigree.

There is a Sicilian proverb I learned from my father; he learned it from his father: "The shepherd saw Jesus only once." The saying refers to the New Testament story of simple shepherds who were watching their flocks when suddenly angels burst on the scene to announce the birth of Christ. It was a magical moment to be embraced and cherished forever. We may not see choirs of angels, but the proverb is a call to revel in every magical moment. "The shepherd moment" I call it, as corny as it sounds to my kids. And so it was that this night at Miroir was one of those rare moments in life when all seems right with the world.

But it was late. Midnight. Time to go home. Tomorrow would be another day on the only street in Paris.