In the wake of a spate of deadly bombings in and around Beirut, I felt like I needed to get out of the city to clear my mind. Tired of the toxicity of hate, and disturbed by the carnage of rockets and bombs, I decided to make a mini-pilgrimage of peace to the final resting place of Khalil Gibran.

Though I'm usually a solitary traveler, I joined up with some out-of-town tourists for a Sunday morning excursion to the Khalil Gibran Museum. Sitting next to me in the van was a middle-aged man from Iraq, who had seen his beloved Baghdad blown to bits. Behind me was a young woman from Ukraine, who couldn't return home because the airport was closed. As for me, I was worried about a student whose house had been blown up by a bomb in Beirut. Though we were all strangers, none of us were strangers to violence, and neither was Khalil Gibran.

As our van weaved through the Wadi Qadisha, the "sacred valley" once populated by Christian hermits and Sufis, I looked up at the snow-capped mountains, and remembered the first time I read The Prophet. It was on a snow day in middle school when I was trapped at home, and my mom suggested I read Gibran's mystical masterpiece -- published after World War I when many were "hungry for beauty, for truth." Little did I know at the time, as I snuggled up on the couch with his "strange little book," that I would one day live in the land he loved -- even though it was (and still is) a "snarled political knot," a religious "chess game," and an "international problem."

Photo credit: Emily O'Dell

Church bells were ringing in the distance when we reached Bsharre (بْشَرِّيْ), where Gibran was born in 1883 under Ottoman rule. After we parked next to the Monastery of Mar Sarkis, where he is buried, I walked to the edge of the plateau to gaze at the mountains he sketched in charcoal as a child -- before his mother, fleeing financial ruin and sectarian violence, took him and his siblings to Boston.

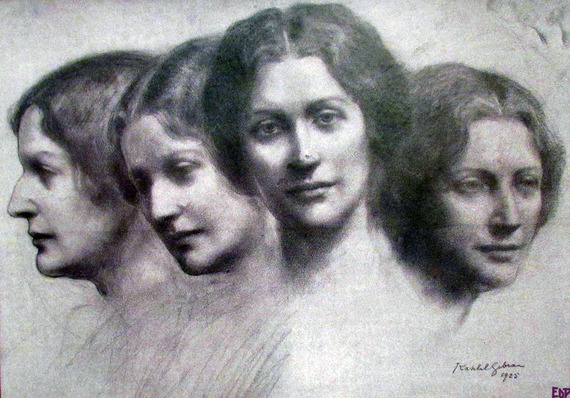

As our group stepped through the cedar door of the museum, we were given a map of the monastery's sixteen rooms, which hold over a hundred of Gibran's original paintings. His artistic gift was first discovered and nurtured by avant-garde artists in Boston when he was just twelve-years-old and enrolled in an arts and crafts class at Denison House -- a settlement house for the poor.

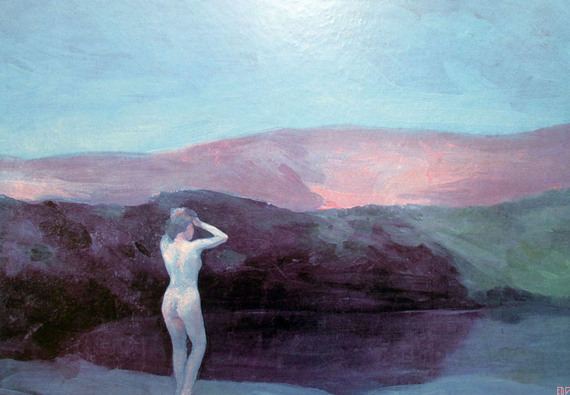

While photographing his paintings of nude women, dancers and centaurs, I spotted a few portraits of the women who had touched his life, such as his patron and confidante Mary Haskell, and his mother -- who died of TB, as did two of her children, in the slums of Boston's South End.

In an artistic style inspired by the mystical paintings of Eugene Carrière, Gibran's dream-like landscapes and solitary nude figures reminded me of the theme of spiritual transcendence that flows through his writing. The artist who "kept Jesus in one half of his bosom and Muhammad in the other," believed that a universal "religion of the heart" could create harmony between people of different faiths. Strongly influenced by Sufism, Gibran once wrote, "I love you when you bow in your mosque, kneel in your temple, pray in your church. For you and I are sons of one religion, and it is the spirit."

As I wandered from room to room, I was kept company by the soothing sound of a small spring sputtering from the stone wall. The sign hanging above the water channel, which read "The Prophet's Spring," reminded me that Gibran promoted the beauty of nature as an antidote to the damage materialism inflicts on the soul.

While surveying the fading titles in his large collection of books, I felt grateful for the unexpected glimpse into the mind of the poet. On the museum's dusty bookshelves, I spotted Chekhov, Shakespeare, Whitman, Goethe, Balzac, Rousseau, Hugo, and Poe -- along with The Kingdom of Happiness and Life in Freedom by Krishnamurti, and Human Personality and its Survival of Bodily Death by Frederic William Henry Myers. Near the books, in vitrines lining the wall, were porcelain figures from Asia, an Egyptian servant statue that looked fake, and a leather suitcase with a metal plate which read:

K. Gibran

51 West 10th street NW

Admiring this worn artifact from the years when Gibran paid just $20.78 a month in rent to live in Greenwich Village, I thought of all the other eyes that had seen it too. After all, Gibran's social circle was composed of the best artists and thinkers of the day -- W.B. Yeats, Carl Jung, Gertrude Stein, Abdu'l-Bahá, Auguste Rodin, Sarah Bernhardt, and Ruth St. Denis.

Though Gibran's art was shown at several prestigious galleries in New York, he never gave up his fight for the poor. One day, after witnessing a noon-time tide of workers in Manhattan, he remarked, "This procession is of slavery. The rich are rich because they can control labor for little payment." In a piece entitled "The Plutocrat," Gibran called the figure of an insatiable capitalist a "man-headed, iron-hoofed monster who ate of the earth and drank of the sea incessantly."

Though it was hard to decipher his handwriting in several letters displayed in a large glass case, my Egyptological training came in handy as I transcribed a letter he addressed to Mary Haskell in 1916 -- a year when dozens were hanged in Beirut and Damascus on suspicion of treason, and monasteries were converted into fortresses.

My people, the people of Mount Lebanon, are perishing through a famine, which has been planned by the Turkish government. 80,000 already died. Thousands are dying every day. The same things that happened in Armenia are happening in Syria. Mt. Lebanon, being a Christian country, is suffering the most.

You can imagine Mary what I am going through just now. I cannot sleep nor eat nor rest. All the Syrians here are being tortured in the same way. We are trying to do our best. We must save those who are still alive. Oh Mary, it is too much to bear, too much. Pray for us beloved Mary help us with your thoughts.

love from suffering,

Khalil

Motivated by the belief that war "robs one's soul of its silence," Gibran became the secretary of the Syrian-Mount Lebanon Relief Committee, and raised hundreds of thousands of dollars in humanitarian aid to ship on a steamer to Syria. For his fierce attacks on the hypocrisy and corruption of both the church and state -- along with fanaticism in all its forms -- his books were burned in Beirut, and he received death threats in America. As he once wrote: "The work I have been born to do has nothing to do with brush or pen."

Though Gibran wanted to spend his final years "in fruitful work and peaceful meditation" in the abandoned Monastery of Mar Sarkis, he died at St. Vincent's Hospital in New York before he got the chance. In his memory, Mary and his sister Marianna purchased his beloved monastery, where his body lies today in an underground grotto surrounded by his paintings.

As I sauntered down the stone steps leading into his crypt, I saw a slim silhouette projected onto the wall, next to these words: I AM ALIVE LIKE YOU AND I AM STANDING BESIDE YOU. Comforted by his posthumous presence, I stepped towards the small opening in the rock to pay my respects to the gifted artist whose life was marred by factional violence but transformed into a compelling cry for peace.

When my fellow travelers and I stepped back into the van, I was no longer lamenting the dire state of the world. For Gibran, the "old corrupt tree of civilization," in all its tragic forms, was "a supreme motive for spiritual awakening." Peace and liberation were not to be found in the "putrefied corpse" of the state, but in the loving heart freed from all attachments.

As my Iraqi and Ukrainian friends and I drove away from the museum towards the snow-covered Cedars, I could hear his words still speaking: "Spare me the political events and power struggles, as the whole earth is my homeland and all men are my fellow countrymen."