What was it like to have a front row seat to the Great War's first months? One hundred years ago, U.S. diplomats, citizens, and journalists in France had a rendez-vous with history. Duties multiplied exponentially overnight, volunteerism fueled multiple relief and medical aid efforts, and reporters overcame obstacles to file news reports from the field. These encounters with danger, deprivation, and drama provide unique accounts of the tragedy's first acts.

The U.S. Embassy in Paris was a beehive of activity as the conflict rapidly spread after July 28, 1914. Despite U.S. neutrality, it was all-hands-on-deck at the chancellery at 5, rue de Chaillot. Thousands of Americans, vacationing tourists and expatriates alike, had to be transported home via French ports. Most required assistance acquiring food, lodging, and money for French banks refused to cash travelers checks or issue currency during the war's first weeks. Even wealthy American travelers were rendered temporarily penniless.

U.S. Ambassador to France Myron T. Herrick was at the end of his tour of duty but remained in Paris to lead the American relief response at the request of President Woodrow Wilson. The former governor of Ohio, lauded in the press for his charm, good looks, and way with people, put his small staff to work. They organized repatriation efforts, checked on U.S. property and citizens in France (including Wilson's sister, Annie Wilson Howe), safeguarded valuables entrusted to their care, and more.

It was not just U.S. citizens that the Embassy contended with. Per requests from Berlin and Vienna, responsibility to care for German and Austro-Hungarian subjects fell to the United States; the Embassy thus provided shelter and sustenance for these charges. After French authorities congregated Germans and Austro-Hungarians into internment and prisoner-of-war camps in mid-August, U.S. representatives visited these sites to represent those in their care and report on conditions.

The Embassy relied upon a corps of volunteers to meet the crushing burden. Future Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg, temporarily marooned by the outbreak of hostilities, banker H. Hermann Harjes, and others from the American expatriate community chipped in. At Herrick's direction, businessmen devised a way to allow U.S. citizens to draw on funds in France, established a fund for those in-need, organized transportation home, and planned how to protect U.S. property and nationals. Eric Fisher Wood, a 25-year old École des Beaux Arts student, went to the Embassy in early August and offered his help. The assistance was sorely needed for, as Wood described it, "virtually within one day, this great flood of humanity had rolled in upon the normally tranquil life of the Embassy."

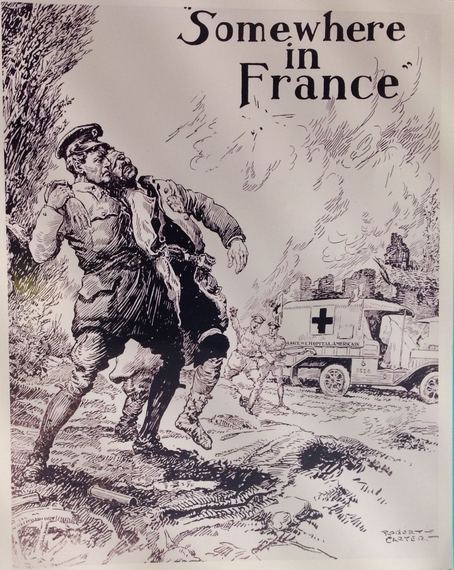

Volunteers aided relief efforts in other ways. In the Parisian suburb of Neuilly, U.S. architects converted the Lycée Pasteur into a modern hospital. The repurposed building housed the American Ambulance Hospital of Paris, an independent institution conceived of by Herrick to treat the war wounded. Herrick's wife Carolyn led the hospital's Paris-based fundraising drive and Martha Bacon, wife of former U.S. Ambassador to France Robert Bacon, spearheaded the effort in the United States. Through their efforts, the American Ambulance Hospital was financed entirely through private donations.

The work was difficult and tiresome. Everybody worked long days and toiled late into the night. Many grew ill from exhaustion. "Yet," Wood noted, Herrick "and his assistants took up the vast responsibility as quietly and acted as coolly as though it were all an everyday occurrence and not the emergency of a lifetime." The crisis escalated in early September when the Government of France departed for the safety of Bordeaux. The majority of the diplomatic corps retreated to that southwestern seaport, but Herrick remained in Paris. Consequently, the Embassy acquired responsibility for several other nations' affairs, including British, Japanese, and Serbian interests. Herrick sent Special Agent John Work Garrett to Bordeaux to represent U.S., German, and Austro-Hungarian matters.

American consuls, especially those in northern France who were at--and behind--the frontlines, had a very different rendez-vous with history. William Bardel, U.S. Consul at Reims, and his family endured the German bombardment of that city and its famed cathedral. "I have had to undergo the most terrible experience of all my life," he wrote of the ordeal, during which a wine cellar served as the family's bomb shelter. In Roubaix, U.S. Consul John Watson faced difficulties after the German Army occupied that city, arrested his deputy consul (a British citizen), and seized the Consulate's telephone.

For American reporters, their rendez-vous with history was shaped by different obstacles: lack of accreditation, transportation, and telecommunications. Paris-based correspondents were initially refused credentials to enter the area of combat over fears that they would publish sensitive information about the French Army. Since automobiles were registered through the Ministry of War--and thus requisitioned for official use--the few vehicles available were those in the Embassy's motor-pool. Lastly, transatlantic telephone lines were commandeered by the military, which forced reporters to file stories by cable (subject to restrictions) or letter (slow).

As Herrick noted, strict military censorship forced U.S. reporters to develop much closer relationships with the Embassy. Journalists needed diplomatic help to procure permission to travel near the battlefront or borrow cars. In return, Embassy officials, overwhelmed by work in those first weeks, relied on reporters for on-the-ground reports. Thus, in some ways, American correspondents were unofficial "journalistic attachés."

Paris-based New York Times correspondent Wythe Williams volunteered in the French ambulance corps to get closer to the story. War reporter Richard Harding Davis filed vivid accounts of the destruction in Belgium and France, even though Allied officials refused to issue him credentials. Both men, and many other journalists, were arrested by military authorities for a variety of reasons. Each time, they relied upon the Embassy to facilitate their release.

Despite drastically different duties and daily lives following the war's outbreak, American diplomats, reporters, and civilians in France recorded their rendez-vous with history and their reactions. For Herrick, incredulity reigned. "The horror of it all," he wrote, "can it be that this is really 1914, the age when civilization has reached the highest point!" Such eyewitness accounts, often overlooked, provide unique views of the Great War's opening acts.

This is the first of a short series highlighting the experiences of the U.S. diplomatic community in France 1914-18. To learn more, we invite you to read "Views From the Embassy" and visit U.S. Embassy Paris' World War One Centenary page.