Euro-area leaders announced yet another agreement with Greece in mid-July. However, the survival of the euro area has never been about the fate of Greece. Instead, it is whether the Europeans will implement the reforms necessary to keep the euro area together. If they do, the common currency will endure. If they don't, then the euro may not survive the next big adverse shock.

Saving the euro requires the creation of a truly pan-European financial system. While a unified financial market would surely improve capital allocation across the continent, it is a full euro-area banking union that is critical. One part of banking union - common regulation and supervision - is now well advanced, following the 2014 implementation of the Single Supervisory Mechanism. Another part, the legal framework for common bank resolution, is in place but inadequately funded. The third and final part, common deposit insurance, now needs to move forward as quickly as possible.

Our view is that unless banking union is completed before the ECB halts its massive asset purchase programs, depositors will flee the weakest links in the euro-area banking system the next time serious economic or political trouble hits. Importantly, this conclusion is not predicated on Greek exit: the prospect of capital controls like those implemented in Greece on 29 June 2015 will be sufficient to make depositors elsewhere skittish.

The key role of banking union is to separate the health of the banks in a country from the fate of that country's sovereign, putting an end to the doom loop that still haunts the euro area today. That is, much like the U.S. banking system can absorb the default of a U.S. state, the euro area's banking system must be able to withstand the default of any single country. If this were the case today, the discussion about Greece would be much more like the discussion about Puerto Rico - messy and unpleasant, but not life threatening and far less acrimonious.

Not only would banking union make depositors indifferent about their bank's physical location, it would also lead to market discipline over euro-area sovereigns. The current system of mutual fiscal surveillance and Treaty-based fiscal rules has fueled rancor among officials and the public without securing fiscal sustainability. In place of today's system, with its national banking champions that tend to receive preferential domestic treatment, all large banks would be diversified and highly capitalized euro-area banks with deposits backed by a credible and well-funded euro-area deposit insurance scheme. These banks' holdings of sovereign (and all other) debt would be subject to tight concentration limits and to capital requirements reflecting the debt's evolving default probability. And, while government debt would remain in the ECB's collateral framework (together with more than 32,000 other securities), it would have appropriate haircuts that rise with market indicators of default risk.

In this environment, sovereign defaults need not threaten banks' health. Should governments try to borrow too much, market risk premia (and ECB haircuts) would rise commensurately with default risk. Contrast this risk-sensitive response with the pre-crisis period, when euro-area prudential policymakers repressed market discipline (and depressed risk premia) by treating all sovereign euro-area debt as risk free, thereby subsidizing unsustainable debt accumulation.

To see how critical this change is, consider how fragile the U.S. banking system would be if it relied solely (as the euro area does) on state-level deposit insurance. Depositors in North Carolina-based Bank of America would be tempted to run at the first sign of slippage in the bank's capital or in North Carolina tax receipts. Indeed, no U.S. state has the capacity to insure the deposits of the four behemoths that account for nearly 40% of U.S. commercial bank deposits. (The last state-run deposit insurance funds - in Ohio and Maryland - failed in 1985.)

The consequence of the failure to carry out financial union has been that, when the public loses faith in either their country's banks or in their government's ability to make those banks whole in the event of a collapse, they can seamlessly move their euro-denominated funds to a bank in another country. Today, Romans can move their deposit accounts to Frankfurt or Amsterdam. And, without the implementation of capital controls, this process can go on until the banks in the weaker nation are drained of deposits. That is, the residents of one euro-area country can run on their banks, re-depositing the funds into banks in another euro-area country. (We discuss the technicalities of this involve in a previous post, and it is explained in detail here.)

Confronting this challenge is straightforward. It requires the completion of the banking union. If Greeks had been confident that their deposits would be available regardless of state of their government's finances, there would have been no run; no withdrawal restrictions; and no capital controls. Their big banks needed to be European banks, rather than Greek banks. This means having mutually and jointly guaranteed deposit insurance.

Of course, implementing greater burden sharing in the aftermath of Greece is politically daunting and may be viewed by many in authority as a nonstarter: indeed, the public shows little interest in a more federal Europe. Yet, deposit insurance would be cheaper for Europeans than the €300 billion they are on the hook for now if, as we expect, Greece defaults or its debt is "re-profiled" to lower its value. Not only that, but people are usually understanding about the need to pay deposit insurance premia (the ultimate burden of which may not fall on depositors anyway).

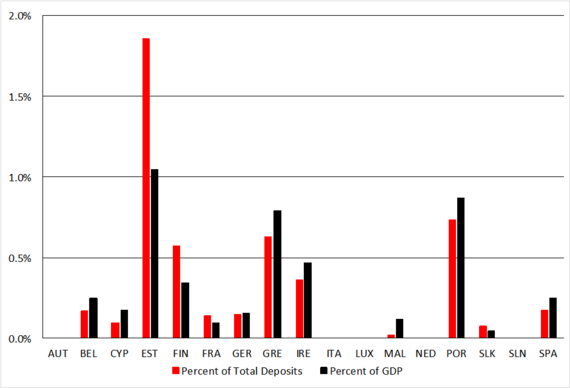

The details of the current European deposit insurance scheme are simple. Deposits in euro-area banks currently total a bit under €11 trillion (about the same as euro-area GDP). While the European Union has an explicit insurance limit of €100,000 that is uniform in all countries, suppose that as a practical matter, deposit insurance covered all deposits (just as, in practice, the U.S. FDIC typically does). As it stands, the national systems are woefully underfunded (see the chart below). And, the target of 0.8% of covered deposits in the April 2014 EU Directive is also inadequate.

Funding of Euro-area Deposit Insurance Schemes (percent of total deposits and of GDP)

Source: World Bank Deposit Insurance Database.

In our view, a more reasonable level of funding would be based on addressing the deposit losses in a severe economic downturn (for example, in 2008-2009, euro-area GDP fell by 5.8%). Suppose that such a crisis were to occur every 20 years, and that banks lost 5% of euro-area GDP that needed to be covered by deposit insurance. Assuming the annual deposit insurance levy would apply to all deposits, and that the fund can obtain a 1% real return, then the actuarially fair premium would be about 20 basis points (roughly in the middle of the FDIC's assessment range.) At current levels, the 340 million people in the euro area would be paying something like €40 billion in insurance premiums each year (less than €120 per capita).

Of course, higher capital requirements would lower both the frequency and severity of crisis, thereby reducing the actuarially fair premium in a euro-area-wide deposit insurance system (see the estimates here.) That said, the fact remains that the Greek crisis is symptomatic of a glaring structural defect in the construction of EMU. Without completing the shift to a common supervisor, a common resolution fund, and common deposit insurance, more countries eventually will follow Greece. And each sovereign default or write-down will threaten that nation's banking system.

We are not expert enough to know whether the required changes can be implemented within the limits of the current treaty governing the European Union, or whether a new treaty is needed. But, as former Bank of England Deputy Governor Paul Tucker said a year ago, monetary union requires not only the homogeneity of bank notes and reserves - the monetary base - but also the homogeneity of bank deposits - M2 or M3 - as well. Without that, without a truly pan-European financial system that is mutually and jointly guaranteed by all of the countries of the Eurosystem, we doubt that the common currency can survive.

This post originally appeared on our blog www.moneyandbanking.com, where you can also find a post describing the choice's Greece currently faces.