A serial about two artists with incurable neurological disease sharing fear, frustration and friendship as they push to complete the most rewarding creative work of their careers.

Read previous episodes here: An Alert, Well-Hydrated Artist in No Acute Distress

"Have you been gambling or wanting sex constantly? Cleaning closets or shopping obsessively?" Dr. Bright asked me. "Sorry," he added, smiling. "I have to ask."

I laughed. I liked my MDS, Dr. Bright, a lot. A year and a half earlier, in January, 2010, I'd run to him from the licking flames of the it's not the worst thing neurologist and the no self-pitiers MDS who'd diagnosed me with Parkinson's. Dr. Bright is welcoming, with a warm smile. There's a freshness and sincerity about him, as if he might feel his patients are the best thing about his work. Four days after my first appointment with him when the plastic travel cup I'd left in his office showed up on my doorstep, I was over the moon about him. In what world does a doctor stop on the way to his daughter's school to return a patient's stupid travel cup?

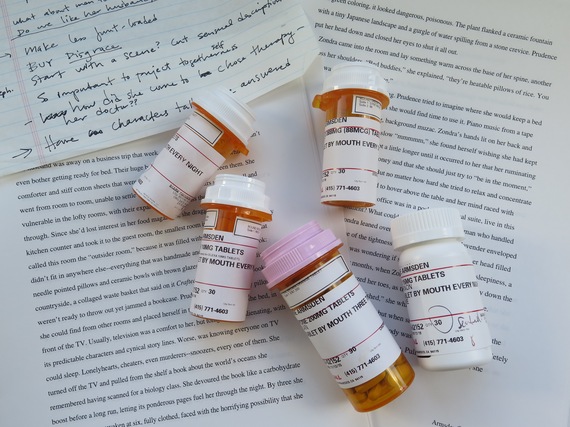

For a year following my diagnosis, my Parkinson's symptoms didn't bother me enough to treat them with medication. When I was finally ready to get some relief for my bradykinesia (slowness) and awkward gait, Dr. Bright thoroughly explained the treatment options, which mainly involve replenishing the brain's dwindling supply of dopamine with either or both of two types of medications. Often the first line of defense is a dopamine agonist, which activates dopamine receptors in the brain that would normally be stimulated by one's own dopamine. In effect, it tricks the brain into thinking it's getting the dopamine it needs. Levodopa, the gold standard medication that every PD patient ends up taking sooner or later, is a chemical that's converted into dopamine by the central nervous system. Developed in the 1960's, it's considered to be one of the most important breakthroughs in the history of medicine. On levodopa, a patient can enjoy many hours a day without symptoms like tremor, gait disturbance and rigidity, and might experience a sense of rejuvenation. Many describe the change in how they feel on the drug as "miraculous;" in fact, without it, someone with advanced Parkinson's can be unable to take a step or even rise from a chair. The medication must be taken multiple times a day to keep symptoms at bay and more and more is needed as Parkinson's progresses. Unfortunately, there's a downside to levodopa: prolonged use can bring on dyskinesia, which causes spontaneous and sometimes relentless, involuntary movements that can look like swaying, jerking or writhing. People often mistake this movement as a symptom of the disease itself, but it's actually a side effect of levodopa that can be as disabling as the PD itself. In some cases, dyskinesia can begin only months after beginning levodopa therapy. For this reason, many, especially younger, patients choose to delay taking it, relying on the dopamine agonists for as long as possible.

During our medication discussion, Dr. Bright and I settled on my starting the dopamine agonist Mirapex. I asked him if he was also going to prescribe Azilect, the medication the MDS who diagnosed me had recommended, and expressed my concern about having to stop the contraindicated drug I was taking, mirtazapine, that had brought my insomnia under control twelve years earlier. Dr. Bright swiveled his chair to face his laptop, pulled up the results of a study on Azilect and carefully explained the graphs to me. "The results of the Azilect study are contradictory," he said. "It seems unlikely that Azilect slows PD progression as we'd hoped. There's no reason for you to stop taking the mirtazapine in order to take Azilect." I was enormously relieved, since by that point, insomnia had been much more of a monster in my life than PD. I also appreciated Dr. Bright's respectful willingness to share the medical science with me.

Now, six months after starting Mirapex, I thought about Dr. Bright's question. I knew that obsessive behavior was not an uncommon side effect of the drug. I told him that the Mirapex helped me walk normally. It also energized me mentally and I was enjoying productive work on my novel, Dream House, which I was revising for the third -- or was it the fourth? Or fifth? -- time.

"No," I told him. "No obsessive behavior."

But the truth was, I was obsessed. I'd been working on the novel on and off for seven years. I had abandoned practicing architecture for something that felt more compelling and immediately gratifying: writing a work of fiction about a woman who practiced architecture. What did I know about writing a novel when I began? Nothing. But I believed I had a good story, that I was the only one who could tell it, and that I had to tell it. I took classes to support my new passion, joined one writing group and then another so I could get the feedback I needed to fuel me. For the first few years of writing I had no aspirations to publish; it was fulfilling enough just to write. But after a couple of years, the story bulked up and became more refined. It began to have the shape of a book.

I was so infatuated with writing that when I was diagnosed with Parkinson's, one of my first thoughts was that being able to walk might be overrated. If I became housebound and frozen in my chair because of Parkinson's, so what? I could still be a writer. (This was before I learned that Parkinson's can cause dementia.) Two months before I was diagnosed, I had joined a writing group in which everyone but me had published one or two novels. Listening to their publishing tales, learning from their insightful critiques and high on their encouragement, I began to allow myself to imagine my novel on a bookshelf. I had a dream. It felt huge. It made my Parkinson's seem like a puny troll beneath a bridge.

During my six months on Mirapex, I showed up at my computer every day, burying myself in the fictional world I'd created. Writers are disciplined; they must be determined. And, at least a little obsessive to revise, revise, revise and then revise again, never knowing whether their work will ever matter to anyone but them. It didn't occur to me at the time that Mirapex was contributing to my drive. But I was acutely aware that the medication had brought back the insomnia I'd mostly licked ten years earlier, making it nearly impossible to exercise and socialize. With the guidance of a psychiatrist, I tried eight different supplements and medications for sleep, but none of them could counteract the powerful stimulation of Mirapex. I was wilted and bleary-eyed. And yet, I remember during those months feeling blissfully drunk on the narrative of my novel.

In April, 2011, my writing group agreed my manuscript was ready to send to literary agents and I sent it out to six, having no idea what to expect. Awake at four-thirty the next morning, I checked my email on my phone, flabbergasted to read a message from an agent who said he'd been up until three a.m. reading, that my book was "really quite astonishing" and he would be in touch soon. I lay vibrating in bed, unable to absorb this unexpected early enthusiasm, waiting for an acceptable time to crow the news to my husband.

"I told you it's a great book," he said, in that confident, sunny way of his.

The agent finished reading the next day and emailed to ask when we could meet. I asked him if we could wait a week so I'd have the chance to hear from other agents. He was accommodating and I alerted the agents that I'd had a show of interest so they'd read my manuscript sooner rather than later.

A few days later, on Mother's Day, blitzed from sleeplessness but high on hopefulness, I was weeding our daughter's bureau drawers, perhaps subconsciously seeking a way to re-experience motherhood while my children were living far away. My cellphone rang with a number I didn't recognize. Since it never occurred to me that an agent would call instead of emailing, I was unprepared for what happened next: a swooning, theatrical bid from the highest profile agent in the group to whom I'd sent my book. She was calling from a cab in New York City, she said, on her way to lunch with (insert name of famous author here), "but I just wanted to tell you how much I love your book! It just screams FILM!"

My husband could tell from the other room that I was having a stressful, though clearly not unhappy, conversation and appeared outside the bedroom. I gave him the thumbs up and closed the door. I needed to concentrate. Now the agent was telling me how the descriptions in Dream House reminded her of the Edward Hopper show she'd just seen at the Metropolitan Museum. Where was she going with this and why was she laying it on so thick? I wondered. After a full fifteen minutes of effervescing about her upcoming vacation in Maine, she delivered the punch line: "I've only read the first one hundred pages, but Lila, my colleague, has read the whole thing and she thinks it's terrific, and the two of us share a sensibility. I am, well, I'm sure you know, I've been in the business a long, long time, and I know what I like and what I like sells, and so if you're ready, Catherine, I'm ready to sign you on."

Blindsided! I tried to think. In two weeks, she said, she'd be on a long flight home from her vacation and she expected to finish reading my novel then, but if I could commit to a contract now, since she was there in The City for the next few days, she'd like to pitch Dream House to some editors. Tomorrow. "So what do you say?"

I felt a little dizzy, walking circles in my daughter's small bedroom. Did agents really take on books they hadn't finished reading? On the other hand, the other agent in her company, Lila, as well as the first agent to contact me seemed to have fallen head-over-heels in love with Dream House. Was it possible I'd written a "hot" book without realizing it? I doubted it; it's a quiet novel, more water than fire. One hundred pages -- what did this agent really know about the story? Then again, I reasoned, she must know what she's doing. She's an expert.

I was confused, the way I had been when doctors were telling me, "Catherine, there's nothing wrong with you." How I wanted to believe them! The agent's gushing offer of representation felt like another dare to hope for something, even as a false note played in my head.

Sleep-starved and overwhelmed, I was in no shape to make snap decisions. But I wanted to throw caution to the wind, to let this powerful agent take Dream House into the world.

Episode Eight of An Alert, Well-Hydrated Artist in No Acute Distress will be published next week. You can also follow the serial here.