Author's Note: This post is the second part of an article series of the same name. You may read the first part here.

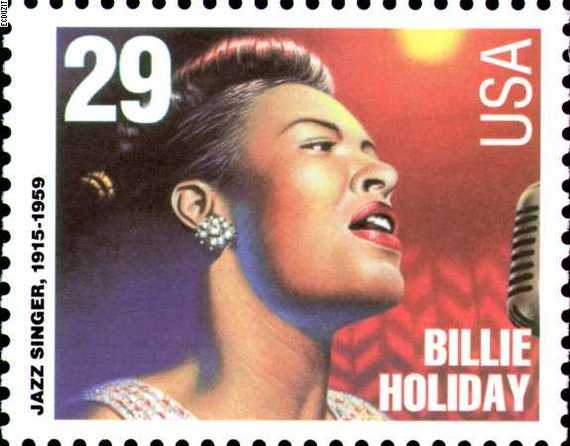

"Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck/For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck/For the sun to rot, for the tree to drop/Here is a strange and bitter crop"

-Billie Holiday Strange Fruit

From Sanford to Long Island, from Long Island to Ferguson, from Ferguson to Cleveland, from Cleveland to Chicago, our nation has received copious reminders in the past few years that its inability to crawl out of its racial quagmire has fatal consequences for many. While certainly it remains difficult to compare and accurately analyze data from different time periods and develop definitive conclusions or causal links, it goes without saying the United States' epidemic of police brutality has deep historical roots, because "the intersection of racial dynamics and the criminal justice system is one of longstanding duration." In other words, instances where police brutality occur often fall along racial lines due to our nation's tortuous history with racial stratification.

Criminologist Katheryn K. Russell-Brown, the late Judge A. Leon Higginbotham, the late legal scholar Derrick Bell, along with numerous other social scientists and legal scholars have continually observed that the history of "racialized" laws and "racialized" law enforcement harkens back to the arrival of the first slave ship in Virginia circa 1619. As Judge A. Leon Higginbotham put it:

[T]he Constitution's references to justice, welfare and liberty were mocked by the treatment meted out daily to blacks from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries through the courts, in legislative statues, and in those provisions of the Constitution that sanctioned slavery for the majority of black Americans and allowed disparate treatment for those few blacks legally "free."

This centuries-old intersection of racial animus and the promulgation of American law represents an amalgamation of physical, behavioral, and psychological components that has led to a tragic cycle of dehumanizing black people, and subsequently justifying their deaths. In so doing, the United States has exhibited the height of its depravity, and depths of its savagery, "with slavery being its cruelest example, but a close second being [it's] infatuation with lynchings." Hence, "those who want to understand the meaning of the American experience need to remember lynching."

Lynchings in the United States represented a barbaric means to brutalize and control blacks through the machinations of state-sanctioned fear and violence; they became "a [literal] spectator sport" for thousands of Southern whites, and further reinforced the ideological underpinnings of segregation through sheer carnage. Whether performed via hangings, shootings, "burning at the stake, maiming, dismemberment, castration, and other brutal methods of physical torture," for nearly a century, lynchings amounted to public, ritualized murder welded by the crucible of racial oppression in the United States. U.S. District Judge Carlton W. Reeves, for the Southern District of Mississippi, said as much in a speech he delivered to three young white men convicted of killing a 48-year old black man named James Craig Anderson, as they went "nigger hunting" one night in 2011. In his speech, Judge Reeves said, "Lynchings were prevalent, prominent, and participatory. A lynching was a public ritual--even carnival like--within many states in our great nation."

Notwithstanding the terror lynchings caused, many stood in vocal opposition to them. For example, Mary Church Terrell, the first president of the National Association of Colored Women, challenged the notion lynchings were perpetrated to preserve the sanctity of white womanhood (as it was often said at the time), or to subdue black people's desires for freedom. Rather, in 1904 she published a piece which declared, "Lynching is the aftermath of slavery." Following the lynching of three of her friends--Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart--Ida B. Wells-Barnett penned a scathing critique of the white-supremacist societal order that could sanction such sadistic violence. In it, she observed, "The world looks on with wonder that we have conceded so much and remain law-abiding under such great outrage and provocation." In another speech Wells-Barnett delivered to a Chicago audience in January of 1900, entitled Lynch Law, she plainly said:

Our country's national crime is lynching. It is not the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob. It represents cool, calculating deliberation of intelligent people who openly avow that there is an "unwritten law" that justifies them in putting human beings to death without complaint under oath, without trial by jury, without opportunity to make defense, and without right of appeal.

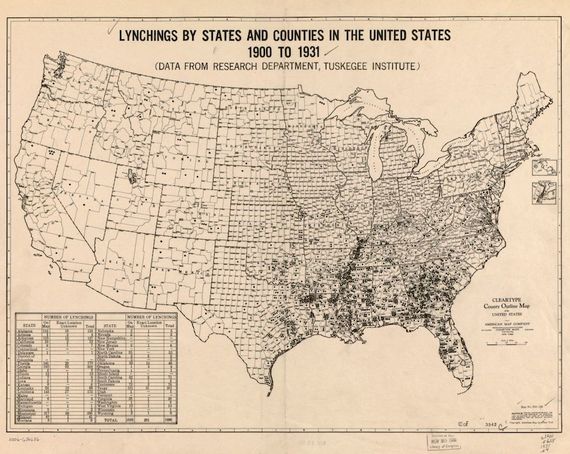

Mainly occurring in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia, the threat of racialized terror loomed large for decades.

Between the years of 1877 and 1950, Equal Justice Initiative documents 3,959 people in a dozen Southern States died at the hands of lynch mobs. The Tuskegee Institute, which maintained a database on lynching between the years of 1882 - 1968, calculated 4,749 lynching deaths, with lynchings peaking in the 1890s. Using the Equal Justice Initiative's records, that amounts to roughly one person per week dying at the hands of a lynch mob during that bloody, seventy-three year period. Using the Tuskegee Institute's records will yield a similar frequency over the span of eighty-six years. Regardless of the metric used, the number of blacks killed by police officers in the past few years are on pace to exceed those ghastly numbers. More specifically, police officers in the United States on average kill one person every eight hours. Considering The Counted's findings that these killings disproportionately impact black people, in the epidemic of police killings, we presently have an epidemic akin unto lynching.

When arbitrary misdeeds and perceived slights--stealing about $3 worth of cigarellos, selling untaxed cigarettes, purchasing a toy gun from the store, being in the wrong place at the wrong time, wearing a hoodie, being "big for [your] age," making eye contact with police officers, refusing to extinguish a cigarette while seated in your car, running away from a police officer, refusing to remove a hoodie, sleeping in your car, walking home early in the morning--can serve as justifications for one's death at the hands of members of society sworn to protect the community, our nation continues its shameful legacy of racial terror and its violent assault on black bodies. We have come this way before. As author and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Isabella Wilkerson noted "banal missteps," the "most mundane infractions," or accusation thereof--taking a hog, making boastful remarks, stealing 75 cents--could result in an hours-long, ritualized, tortuous public spectacle of lynching.

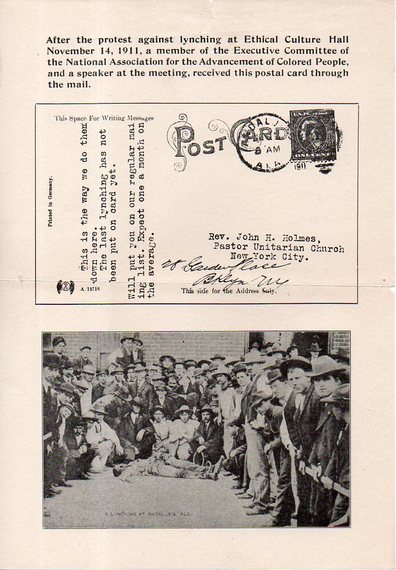

Aside from the similarities in the sheer volume of blacks killed by police and those lynched decades before, there remain other staggering parallels between police killings and lynchings. The extreme, pitiless killing of the victim, the casual disregard for the victim's body, the swiftness to shame him/her as a means to rationalize his/her death, the makeshift protests and public grieving for the victim, all are common themes between lynchings and police killings. The grainy cell phone footage of bystanders filming people killed at the hands of police officers continues the public spectacle of black death that lynchings portrayed. Furthermore, historically, this assault on black bodies occurring during lynching went largely unpunished, despite their public nature, which was often captured by photographs, memorialized on postcards, and enshrined by souvenirs. It was almost unheard of to punish those who participated or failed to intervene in lynchings. Similarly, it is astonishingly rare for a police officer to face punishment for killing in the line of duty (especially if the victim is black), regardless of how heinous the killing, and regardless of whether the public witnesses their grave misdeeds. Thus, similarly to how Ida B. Wells-Barnett observed lynchings "represent[ed] an 'unwritten law' that justifies [lynch mobs] in putting human beings to death without complaint under oath, without trial by jury, without opportunity to make defense, and without right of appeal ... " allowing police officers to use lethal force with little to no accountability for the use of said deadly force morphs law enforcement into judge, jury, and executioner. It further perpetuates the notion seared into the psyche of lynch mobs--blacks may be killed with impunity. It is a deadly proposition.

Despite these striking parallels, lynchings and police killings are not mirror images of each other. Police officers are not private citizens, but rather are members of society entrusted with great responsibility to serve and protect the community. In the instances of police brutality, it is the agent of the state abusing its power rather than private citizens conspiring against other private citizens. These patterns of abuse from numerous police officers across the nation signal an institutional, structural affront to the public welfare and safety municipalities entrust police officers to uphold. Black people in America bear the brunt of these abuses, many times due to the intentional, systematic discrimination on the basis of race. While these killings by police officers may not mirror lynchings, they certainly descend from the same line of racialized antagonism, terror, and violence. To further this point, Gyanna McMillen did not suffer the gruesome death of Mary Turner, yet both fell victim to a society that could sanction their deaths--often with the complicity of the state--for reasons that seem incomprehensible. Lynchings reinforced the notion that black bodies "were consumable, whether by burning or dismemberment," and police brutality dehumanizes blacks and perpetuates notions of injustice and stratified America. More particularly, in the same manner in which Mary Turner, Marie Scott, Maggie Howze and Alama Howze demonstrated the horrors of lynching befell women, Gynnya McMillen, along with Rekia Boyd, and Aiyanna Stanley Jones reveal the terror of police brutality visits black women and children.

Lynchings persisted at epidemic proportions for nearly a century because the state turned a blind eye, and/or offered a willing hand, to its homicidally deranged citizens. Police brutality and extra-judicial killings persist in large part because the system allows the classification of race to slide its scales of justice. It is further facilitated by the calculated manipulation of the grand jury process as a tactic to achieve the desired result of absolving police officers implicated in the death of black people. It is demonstrated in the efforts to label legitimate critiques of state-sanctioned violence as a "war on police," when such a allegation could be no further from the truth. Last year doubled as a year when police officers killed more citizens than any other time in our nation's history, and the second safest year ever for law enforcement in the United States. 2016 is on pace to continue that trend, yet 167 people have already died at the hands of law enforcement, all the while overtures insinuating critiques of such deaths are "outrageous," "racist," and "anti-police" persist. We have come this way before, and in so doing learned history has an ugly way of repeating itself.