Why must this one bear a Biblical name?

I have known many big storms.

I have purposely placed myself in their paths for the stories that might follow. I have waded in wreckage of storms already passed.

But this one's personal.

Matthew, building to Category Four at this writing, apparently will be raking the eastern coast of Florida with a ferocity like few others. And instead of steering out to sea and riding that warm Gulf Stream north as eastern seaboard hurricanes often do, this one is projected to brush the northeastern Florida barrier island my family calls home.

We've been in the path of these nuisances once before. Years ago, a low-grade storm washed over Tallahassee, the forested town where we lived for many years, while we were away from home. We returned to find several Southern pines, their shallow roots easy picking for a big blow, laying in a circle around our unscathed house in the woods.

Stationed in Tallahassee, as longtime chief of The Miami Herald's state capital bureau, I represented a sort of forward operating base for storm chases across the northern Gulf of Mexico coast. My mission: Get ahead of them, seek shelter -- preferably on the second floor of a motel, always simple because they'd been vacated -- and wait. There was a certain skill in selecting one's lair before the landfall.

My first journey carried me to Lafitte, Louisiana. Hurricane Juan had barreled up the Gulf in the fall of 1985, sinking an offshore oil platform and leaving several people dead or injured. This time, I'd arrived in the near aftermath, on deadline, only to find flooded streets and a graveyard where mausoleums had flooded with water and sealed coffins where bobbing on the floodwaters. It was good enough to grab a quote and a dateline, file for the mid-afternoon edition of the newspaper known as "Street" and head north to New Orleans for an early dinner.

At K Paul's Louisiana Kitchen, they had a policy of filling every seat. A party of two waited in line for another party of two before taking a table of four. This party of one waited for a party of three, which arrived in the personage of a chip salesman, his wife and child -- potato chips, that is. He was the regional rep for a well-known brand in Syracuse, New York. We struck up a ready conversation about newspapers and potato chips, and the three of them watched in amazement as I sampled nearly everything on the menu and topped it off with a fat slice of sweet potato pecan pie and a cognac. These were the days of expense accounts.

One night, parked in Panama City, Florida, for the arrival of another less memorable storm -- I'd learned not to worry much about Category Ones -- I hitched a ride in a military Humvee with a National Guardsman for a tour of flooded streets and delivery of emergency supplies for elderly, stranded storm-sufferers. As the truck descended into a deep pool of water, the driver eased my concern by explaining that, so long as the "snout" atop the hood of the vehicle remained clear of the water, the massive engine would roar. This, as the storm water rose to our waists inside the cabin.

Back at the emergency command post, where I witnessed the biggest cardboard box of frosted donuts I'd ever seen, I stepped outside long enough to watch metal strips of roofing fly through the dark air. Cat One or no, I was staying inside.

As it turned out, a lot of this served as dress rehearsal for the big ones. I was an amateur, flying by the seat of my pants. The old Radio Shack plastic laptop computers ran on AA batteries, the syrup-slow modem connecting to pay phones with rubber couplers -- and I came to learn that pay phones generally worked during the onslaught of tropical storms and worse. One night in a booth, I fumbled the phone and dropped the computer on the cement floor. Keys popped off the keyboard. When I turned it on again, oh say, I could see, my story was still there.

The real pro was my colleague, Phil Long, stationed for the Herald in Vero Beach. He kept "go-boxes" in his garage, pre-packed milk crates carrying the essentials for an array of storms, from smallest to largest. The largest included a generator -- it would serve him, and the dispatched Herald staff as well, in the storm to come.

In the summer of 1992, Hurricane Andrew made landfall south of Miami in the middle of the night. It arrived as a Category Five, the top of the Saffir-Simpson scale, storms with sustained winds exceeding 155 mph: By the scale: "Complete roof failure on many residences and industrial buildings. Some complete building failures with small utility buildings blown over or away. Major damage to lower floors of all structures located less than 15 feet ASL and within 500 yards of the shoreline. Massive evacuation of residential areas on low ground within 5 to 10 miles of the shoreline may be required." Autopsies of the damage later suggested it actually may have broken the scale, winds approaching 200, a category of its own.

In the morning, Florida Gov. Lawton Chiles and U.S. Sen. Bob Graham boarded a small state plane in Tallahassee. At first, there was a question about an available seat for this reporter. I explained in no uncertain terms: "The Miami Herald is getting on this plane." We flew along the black back wall of Andrew as it lumbered west out toward the Gulf. We landed at Opa-locka to board two Blackhawk helicopters. Strapped in at the shoulders and waist, we flew open-doored for a long low-altitude survey of Homestead, a long landscape of ripped-off roofs and homes reduced to rubble. As we swung around, the brick-sized Motorola cell phone I was using to dictate observations to the Herald fell on the floor of the chopper. Unable to bend down, I worried that some poor homeless hurricane victim below was about to take a falling brick on his head. A National Guardsman lifted the phone with his feet and returned it to me. One of the more startling scenes as we circled north along Biscayne Bay was the sight of seagrass on the bed of the bay all laying in one direction, the same direction that the fallen Australian pines of southern Key Biscayne were pointing. We slept in a hotel without power, light or air -- the windows sealed on a steamy summer night.

My byline led the first story in the Herald.

The next morning, we flew back to Homestead for a ground-level survey, trudging through the wreckage of people's homes, not only the roofs, but also walls gone. It remains the worst hurricane I've ever witnessed -- though I had missed its actual onslaught. This was one of those times I was fortunate not to get ahead of it.

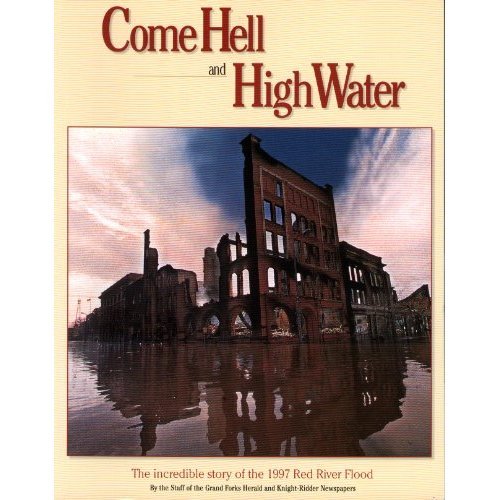

My experience was earning me some creds in disaster reporting. I'd made good personal contacts with some of the many good people who work for the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which is not a bureaucracy so much as a posse that stands up local help when trouble arrives. When trouble arrived in Grand Forks, North Dakota, in 1997, I was summoned to town. The Red River, in a surge of 100-year flooding, had breached the dikes and inundated Grand Forks. Downtown, buildings not only flooded but also burned to the ground -- including the local paper, the Herald, a sister paper of mine in the Knight Ridder family.

A swarm of editors and reporters from around the country arrived in Grand Forks to publish a paper whose staff was literally underwater, their lives devastated. We were publishing from the computer lab of a little school up the road, a roomful of old Macs and actual floppy disks. We emailed our work to another sister paper in St. Paul, Minnesota, which printed it before its own went to press, and trucked it back to Grand Forks. I was asked to work the disaster forces at FEMA. But my own state editor, who'd arrived before me, pulled me aside for one special assignment: "I want you to find out who this 'Angel' is."

An anonymous angel had donated more than $20 million for flood relief while asking to remain nameless. Apparently, few but the bank president, governor and senators knew the donor's identity. I went to work at the state university library, on Harvard Street, where the Internet was still working. Then, after narrowing the field to a few suspects, a tipster informed us one night that a private jet had landed at the airport. We ran the tail number. It was one of my candidates: Joan Kroc, widow of the McDonald's hamburger mogul. Only the governor, senators and other leaders could confirm this for me. When I wrangled a confirmation -- and a cussing-out by one certain U.S. senator who likened me to a lousy carpetbagger -- the paper went to press with a front page story, ignoring the threats of the community's powerful heads. The publisher of the paper stood in the little computer lab that Sunday and told us: "This is what we do. This is why we're journalists."

After a few weeks of roaming around much of northern North Dakota in a rental -- a Chevy Blazer II -- my red ride was caked with dirt. I thumb-printed the phrase "Come Hell and High Water" along the doors on both sides. This was the theme of the paper that never missed a daily beat, despite the flood and burning. At a gas station, someone asked me: "Was that professionally done?" Yes, I replied, I am a professional.

After months of courageous reporting, the staff won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. We visitors were given certificates: "Loaner Pulitzers."

The next year, as Hurricane Georges wreaked Category Four havoc in the Caribbean, ran over the Florida Keys and put a bead on New Orleans, my Herald dispatched a small army of photographers and reporters to do what we do in the face of storms: Get in front of them.

There was a lot of work to do. In the middle of the night, I received a call from my state editor: "We've got a problem. The Herald trucks can't get into the Keys. The police are stopping them." I called the police and explained the importance of people getting emergency information. They were unswayed. It was so important, I said, that I'd have to call the governor and wake him up (pondering, as I uttered these words, how unlikely that was). "No, don't wake up the governor,'' a cop said. "I'm gonna have to wake him up," I warned. Next call received:"Trucks rolling."

I headed west in a rental car -- one never takes one's own into a storm. As I drove toward New Orleans, I received a call that Georges was shifting eastward toward Biloxi, and New Orleans should be clear. Trouble was, one of our photographers had been stranded there and needed a way out. I drove on. As I started crossing the causeway at the eastern approach to the city, water was rising in the roadway. Soon I was having trouble seeing the road ahead. I backed up and made a wide loop over the top of Lake Pontchartrain and approached the city from the west. Police officers at a blockade stopped me and warned that I couldn't continue. I explained that I was rescuing a photographer, a colleague, a woman alone without transportation there, and that we needed to get to Biloxi.

I doubt it was the damsel-in-distress story that convinced them. They probably figured, two less reporters.

By the time Georges landed at Biloxi, it was significantly weakened. But it had knocked the power out, and we traveling Herald reporters and photographers were asked to stay for a few days and help the Sun-Herald publish. No prize this time.

By the time a big one finally reached New Orleans, I had left The Herald and left Florida. But as the White House correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, I had the privilege of catching a ride to the Gulf Coast with President George W. Bush in the days after Hurricane Katrina, Cat 5, assaulted New Orleans and the coast, this time flattening Biloxi with its punch. This was the "Heckuva job, Brownie" tour in which the president commended FEMA chief Michael D. Brown for his response to the storm -- a federal response that ultimately went down as the worst ever. We rode flatbed trucks through blocks of New Orleans -- though not the worst-hit parts. It seemed to me that the French Quarter looked pretty much as it might on any Saturday morning. We slept in rock-band tour-buses parked on a dock.

Katrina was the last big storm I've reported on -- instead following up with assessments of how badly the federal response affected the presidency of the leader who first made a lonesome Air Force One flyover of the storm's devastation before actually going for a first-hand look. I even had a chance to catch up with Brown again to find him in Colorado, among other pursuits, working as a contractor with FEMA repairing cell phone towers downed by big storms. This made for a pretty good story at The Tribune. The days of the pay phones and the rubber couplers are long gone. "I probably, at any one time, have a half-dozen clients involved in different things having to do with homeland security or government in general," Brown said in our interview. "I am called corporate advisor. Some places, I am called vice president for corporate relations. I am called all kinds of names."

Now Matthew, a Four.

By the Saffir-Simpson scale: "More extensive curtain-wall failures with some complete roof structure failure on small residences. Major erosion of beach. Major damage to lower floors of structures near the shore. Terrain continuously lower than 10 feet ASL may be flooded requiring massive evacuation of residential areas inland as far as 6 miles."

(Update Friday morning: Matthew has lost 20 mph of its sustained winds, a Cat Three now, and has spared the southeastern coast of Florida its wrath after ravaging Haiti. Still the day is long, and the tide will be low this evening on the Northeast coast, so these are welcome signs.

Nevertheless, this is what a Three involves, according to the National Hurricane Center: "Well-built framed homes may incur major damage or removal of roof decking and gable ends. Many trees will be snapped or uprooted, blocking numerous roads. Electricity and water will be unavailable for several days to weeks after the storm passes.")

I'm not getting in front of this one.

My family's gotten out of the way. And if there is any story to tell, I may well be telling it to my insurance company.

(Final postscript: Saturday after the storm: Matthew rumbled 30 miles offshore past the beaches of our community, downgraded to a Cat Two and tossing tropical storm-force winds ashore. The beaches took a beating, but the bridges from the mainland were reopening to traffic today and we'd learn soon what, if any, damage our neighborhood bore: None. Free and clear.

The mayor of Jacksonville Beach was on TV today saying: 'By the Grace of God, that thing went a little bit to the East.")

Biblical to the end?

That's why they call these "things" Acts of God.