There are a lot of hard truths to confront about the indigenous people of North America. The list starts with one very uncomfortable contradiction: The United States of America is the most prosperous nation in the world, but many of its tribal reservations suffer from third-world conditions.

The suffering is widespread, with at least 38 percent of reservation residents living below the federal poverty line. About 90,000 Native American families are homeless or under-housed; less than half of those living in houses have access to a public sewer; and in many of these households, utilities are viewed as a luxury. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the average life expectancy for Native Americans trails that of other Americans by almost five years.

The hardest and most bitter truth to confront is that their struggle is largely ignored by the political powers that be.

In part, this is simple mathematics. The 5.1 million Native Americans that live in the United States comprise less than two percent of the population. It's a minority vote in the minority voting bloc, and politicians have traditionally targeted larger segments of the population to power their campaigns. To do otherwise runs the risk of bringing Native issues to the fore and confronting that most egregious contradiction: Preaching the American Dream when that dream has been consistently denied to the people that originally lived here.

The Native struggle also owes its marginalization to the complexity of the laws that govern it. For example, the tangled web of tribal and federal law nominally gives tribes the right to govern themselves. However, until recently, tribes had no authority to prosecute violent crimes that happen within their reservation boundaries. For years, whites could commit violent crimes on reservations and remain untouchable to tribal police.

This legal nightmare extended even over marriage. It prevented Diane Millich, an Ute woman living on a southern Colorado reservation, from seeking any protection against her white husband, who beat her regularly. The Southern Ute Tribal Police could not arrest him and, because the couple lived on the Ute reservation, the husband resided outside the jurisdiction of the La Plata County sheriff. Millich went to the federal authorities for help and received none. In fact, Millich's domestic nightmare would likely have continued had her husband not shown up to her office one day and shot her co-worker.

It is this absurd and dangerous state of affairs that led Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) to co-sponsor the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013, which expanded tribal governments' jurisdiction over domestic violence crimes and provided funds for tribal criminal justice systems and victim services.

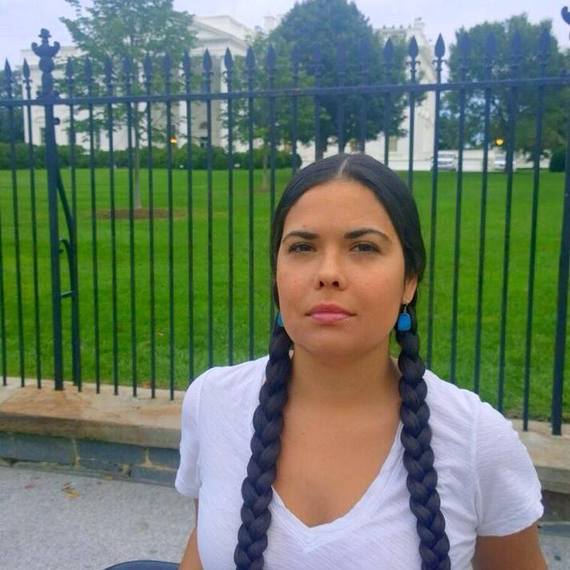

It is Sen. Sanders' recognition of the deplorable conditions on tribal reservations that has led him to become the first presidential candidate to actively involve Native Americans in his campaign. The most promising sign of that involvement arrived on February 22, when Sanders appointed Tara Houska, an attorney and member of Couchiching First Nation, as the Native American advisor to his campaign.

Tara Houska Is Not Your Mascot

Tara Houska is the founder of Not Your Mascots, a non-profit organization "dedicated to addressing the misappropriation of indigenous identity, imagery and culture." This mission has received recent attention with the effort to eliminate the name and logo of the Washington Redskins, which most Native Americans consider harmful ethnic stereotyping. In actuality, the fight against indigenous stereotyping in sports mascots has been going on for decades.

"It's been happening since the early 1960s," Ms. Houska told Planet Experts. "To put that in context, that was still the same period of time that the federal government was taking Native American children away from their families. This was still so important of an issue that they protested."

2016 marks the 24th year in a row that the Washington football team has fought against changing the name in federal court. "It's incredible," said Houska. "People ask, 'Why now? Why this moment?' Actually, this has been happening for a really, really long time."

Houska is an attorney in Washington, D.C., and much of her work has involved advocating for what amounts to basic human dignity.

"Living in D.C. can be hard at times," she said. "When you are advocating on behalf of tribes and getting ignored a lot of the time, and then you factor in, okay, the only representation Native Americans have are stereotypes and people do not want to listen to us... We protest and people laugh in our faces and go by doing war whoops, call us [too sensitive]." When Houska laughed, it was from equal parts amusement and frustration. "Native Americans are some of the least sensitive people. We have undergone almost every atrocity imaginable, so to call us too sensitive is laughable at best."

Genocide tends to endow its victims with a particularly thick skin. All Native Americans are asking for, said Houska, is for the rest of the country to stop doing the equivalent of "redface." The civil rights movement in the 1960s coincided with the end of black face, said Houska. "That was the outcome of the population standing up and saying no more. We've been trying to stand up and say no more for a long time, and people are finally noticing."

Joining the Bernie Sanders Campaign

Sen. Sanders is the first politician Houska has publicly campaigned for, and that's because the candidate has proven his support for Native issues with deeds as well as words.

"I've never campaigned before, ever," she explained. "For this particular candidate, the reason I got involved is because I saw someone who, upon realizing that Native Americans were essentially locked out of the conversation, quickly responded to it."

For Houska, this moment came late last year when the Senator co-sponsored the Save Oak Flat Act, a bill to repeal the Southeast Arizona Land Exchange. The Land Exchange was a controversial measure that was twice pulled from consideration because of its unpopularity in Congress. Opposed by hundreds of thousands of grassroots activists and tribal governments for over a decade, the Land Exchange would transfer ownership of Oak Flat and nearby lands from the Tonto National Forest to Resolution Copper Mining. To get around the complications of actually passing a separate bill, three Republican legislators, including John McCain, added the Land Exchange as a "midnight rider" onto the National Defense Authorization Act.

Adding the Land Exchange as a rider to the federal defense budget is itself a sinister bit of sausage making, but the real travesty is that the lands in question were held as sacred to the San Carlos Apache Tribe and other tribes in the region. Suffice it to say, the tribes were not letting that land go without a fight, and Sen. Sanders took notice.

"[Sanders] met with the Apache people," said Houska, "and introduced the Save Oak Flat Act the next day."

After joining Sanders' campaign, Houska has participated in several meetings with the Senator and his wife, Jane. "She's out in Arizona doing outreach in Indian country on the campaign trail," Houska told me in early March. "I think it's incredible that Bernie actually took the time to meet with tribal leaders up in Minnesota just days before Super Tuesday. We are a small segment of the population, but for Senator Sanders, every voice and every vote truly matters."

Houska's primary role in the Sanders campaign is to draft the Native American platform and policy, as well as interact with the press. When I spoke to her, she had just finished running a breathless 18-hour day in Maine. It was exhausting, said Houska, but gratifying. "I think this is pretty empowering for tribes, to know that we are being courted by a presidential candidate, being included, it's an incredible moment for us."

This article originally appeared on Planet Experts.