Bill T. Jones has a long history of pushing envelopes and challenging audiences. In the 1970s, when he was getting his start in New York's downtown dance scene, it was by the pioneering way he - a long, strong, six-foot-one African-American man - partnered with his lover and collaborator Arnie Zane, a five-foot-four Jewish-Italian. Later, it would be by revealing his HIV status - but refusing to serve as a poster boy for the sweeping epidemic - and still later for exploring mortality in works like Still/Here, which featured real people talking about death, life, and illness in a work New Yorker critic Arlene Croce called "victim art," and flatly refused to see (but not to review). Most recently, Jones explored race and history in Fondly Do We Hope... Fervently Do We Pray, a challenging work commissioned for a festival honoring Abraham Lincoln, and announced an impending merger with New York's Dance Theater Workshop in a new venture to be called New York Live Arts, a move that rattled some dance-world insiders.

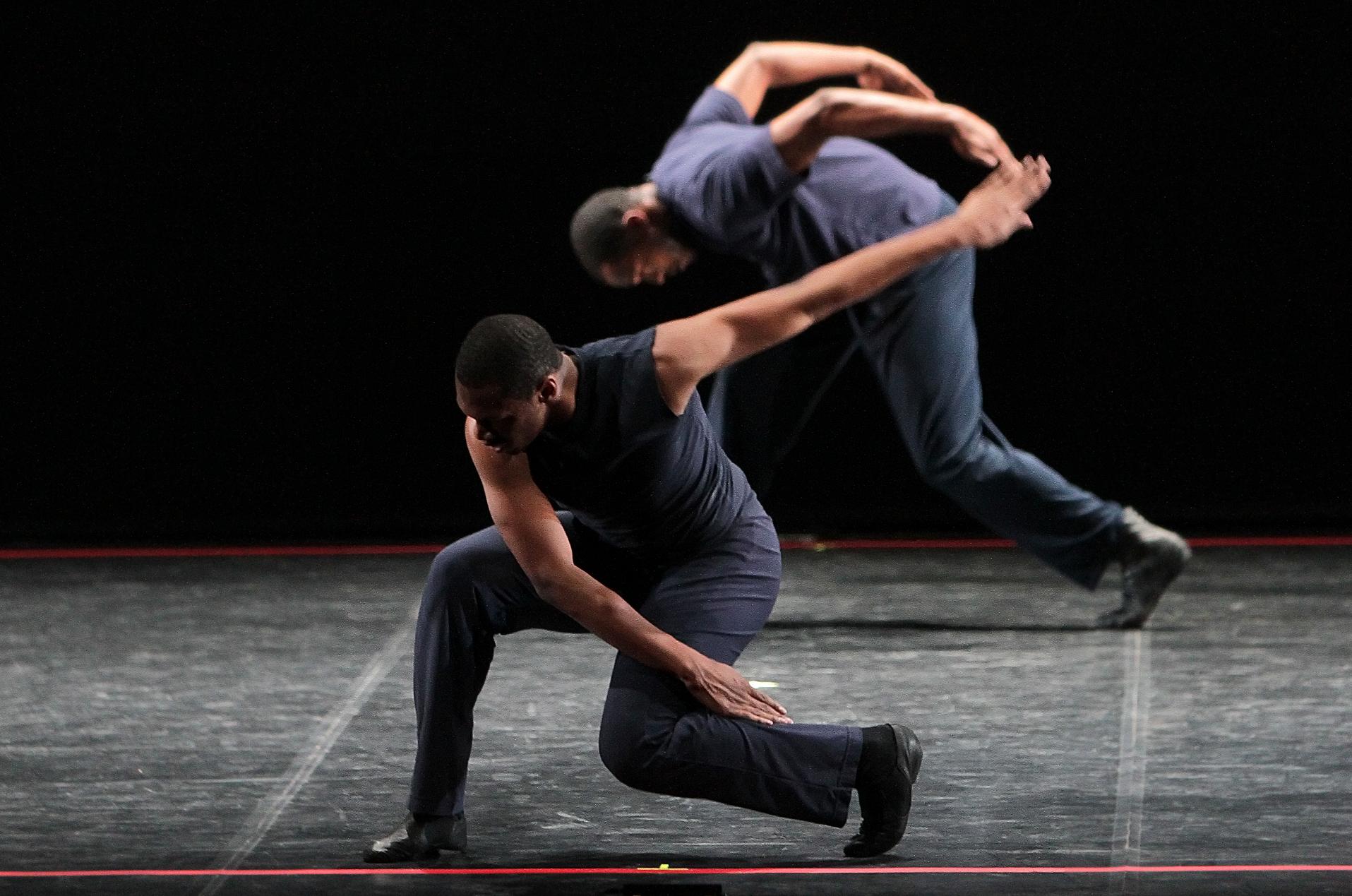

This weekend, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company will premiere at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston Body Against Body, which comprises duets originally choreographed and performed by Jones and his late partner Arnie Zane in the 1970s and 80s, including Continuous Replay (1978), Blauvelt Mountain (1980), and Monkey Run Road (1979), some of which have not been seen since. Spare, athletic, and angsty, they are works produced in a different time, by, as Jones might say, a different Bill T. Jones: before he and Zane would be diagnosed, on the same day, with HIV, and Zane would die of AIDS-related illness in 1988, before Jones's commercial successes on Broadway with Spring Awakening, which he choreographed, and Fela, which he co-conceived, directed, and choreographed, before the Tony Awards for those productions, before receiving a Kennedy Center Honor alongside Oprah Winfrey and Paul McCartney last December, and before building a new life with partner Bjorn Amelan, also the company's creative director.

Brainy, statuesque, and inspiringly vital, Jones is a joy to engage. We spoke by phone about the premiere, his legacy, where dance is moving, and his upcoming projects (including Superfly, the musical).

If Body Against Body was the first work of yours a person was going to see, what would you tell them?

Wow. They've heard about Spring Awakening, they've heard about Fela, and now they're going to go and see two guys pushing a box around on the floor and talking to each other and repeating rudimentary gestures over about 50 minutes? Well, I think you should tell them that they're seeing seminal works from a person who is now in a second or third phase of his career and that this could be an evening that explains how artists truly develop and evolve. They should come knowing that they're only going to see a facet of who this man is. And it behooves them to give themselves to it, learn what they can, and then compare it to something like the Lincoln project, which is a very big, public-spectacle work, and then understand how difficult it is to sum up what an artist does in one piece. Also, I'd tell them to watch themselves watching this work and ask themselves, What do you think these young guys were being fed on at that time: literally, culturally, philosophically? What were they trying to express, what were they obsessed with? That's a lot. But I think that would be a fair way for a person to come.

What is it like to return to these pieces 30 years later, when so much has happened to you, and you've shifted your focus so much from what you were doing at the time?

You mean that I've grown? That life has not stood still? It's like asking a person about their youth, in a way. When we were reprising Blauvelt Mountain maybe 10, 11 years ago, I was worrying whether a new generation of dancers could do work that was so intimate to my relationship with my companion, and Deborah Jowitt, the Village Voice dance critic said to me, "Bill, get out of the way of the work." That was kind of a zen moment - a zen slap, if you will. I was being extremely self-concerned, and not thinking of the work as independent of my own life or career. I feel in some ways that I've gotten over that hurdle now, but there's also a bit of a sadness that comes with it. It used to be, in some ways, the language of our love, between me and Arnie Zane. Of all the billions of people on the planet, he was the only other person who knew that part. Now other people know it. That is a wonderful thing. But it also says that the initial conversation is no more.

I keep thinking about the Marina Abramovic retrospective at MoMA last year, where they took these intense, passionate, powerful, dangerous, sometimes scary performances that she had done alone or with her lover, Ulay, and reprised them with these mostly very young, very beautiful dancers and performers, and how the pieces were really very different...

Well yes, I know exactly what you're getting at. That is the lesson that time and experience teaches us, again and again: that if your work is truly made for the world -- and Arnie and I certainly wanted our work made for the world -- there will come a time when the work must have a life independent of yourself. This raises questions about your ability to communicate intention, about your sincere ability to see the work, or hear the work speak to you. Sometimes the work is telling you, "Look at me, I can be this. I can be this, too. I am not only what you think I am. I am something else."

How did you select which dancers would perform which pieces?

That's much more difficult. When we were re-doing Blauvelt for the first time, I thought our body types - Arnie Zane was 5'4", I'm 6'1" - were essential to the problems of leverage and power sharing in the work, so we need to find a short man and a tall man. But that seemed kind of tone deaf to the fact that our company now had women, so I tried to ignore gender and just find the people in the company who could remember the instructions, which are quite complicated. Who can do it? Who can handle it intellectually? Who can handle it physically?

I have now decided a couple of things. I could be wrong, but I don't think it works between two women. Two men don't necessarily guarantee that it works either. I am lucky enough to have a couple in the company, Jennifer Nugent and Paul Matteson, who have a close relationship to the ethos that informed Arnie and I. They understand the tone of the piece, the way the partnering and athleticism has to work. She is extremely strong and very androgynous looking; he is a handsome and fiercely intelligent animal mover. They bring something to it.

The work I'm dying to see is Monkey Run Road, which has not been seen since we first started doing Blauvelt, probably sometime in the 1980s. Janet Wong, my rehearsal director, has taught the combinations to a whole host of people. There are two men - Erick Montes, a small, Mexican man, and Talli Jackson, a mixed-race man, a big guy - who have a sense of the fierceness of the physical. The other part is there's talking in it, there's singing in it, there's kind of a wry and ironic distance that we had from the material, Arnie and I. They are working on that.

I don't want this question to sound impertinent, but if these works were avant-garde when you made them, are they still avant-garde today?

Well, you know, people in the avant-garde are embarrassed by use of the term now. Nobody uses it - it sounds a little uncool, self-conscious and art-historical. And it tends to place the practitioner in a kind of a box, a place that doesn't allow you to get your roots down in the moment. But the works are still challenging, and when people applaud at the end of a piece like Blauvelt, they have been on a journey with you; it's like watching a long-distance race, and they're wondering if you'll make it. It's challenging, and it's not for everybody. And if that's the definition of avant-garde, then I suppose they are.

Your career has taken you everywhere from the avant-garde to Broadway. Which works do you think have been the most radical, or challenging, or have changed the perspective of the most people?

I think Blauvelt changed a lot of people's ideas about partnering, because of the way in which Arnie and I partnered. And Uncle Tom's Cabin was seen by many, many people - some of whom were in what you call the avant-garde, and never thought of me as a black man who wanted to find a black voice - and the end of the piece had 52 naked people of every shape and size and color on stage, with my fully clothed, churchgoing mother amongst them, praising god. I think there were a lot of assumptions about the alienated, secular avant-garde being challenged in that work.

Still/Here dealt with the issues of mortality at a time obsessed with AIDS. To this day people are still confused about what that work was. The shorthand is it was a piece about AIDS, but it was a an age-old topic about life and death and mortality - the human condition, if you will. Most of the people who were resources for it, in the videos and so on, were not in the dance world, and as a result, it reminded people once again of how this art form can actually participate in the public discourse, and not just the art-journal discourse. That was pretty radical. And it's taught to this day in departments around the country, and I dare say around the world. So take your pick.

It's not very often that you can say that dance is participating in the public discourse.

No, it isn't, and you definitely pay for it when you do, because dance is controlled by an academic and critical establishment that has very particular notions about what is valid. But you know, that's not really how history is written, and that's not really how the levers of culture operate.

I was watching the Kennedy Center Honors this year and thinking about how the public still has so little access to dance. And I don't just mean physical access; I mean mental or intellectual access.

Oh, it's true. I hit the art world in the 70s, and it was supposed to be the revolution of dance; people were saying that dance was the future. What happened to that? Why does PBS do so little dance programming anymore? How often does one see dance programming of any description on the major networks?

And what you see is just the Nutcracker...

...And the proliferation of reality shows like So You Think You Can Dance, and Dancing With the Stars. And if a person knows anything about the development of theatrical dance, those shows have very little to do with what we call dance. But culture is kind of a thick-skulled creature. You can yell at it all you like, you can badger it, but you have to find other ways to help this creature develop a taste for what you think they should be tasting.

My god, when I look at the young Internet generation thinks culture is, I'm sometimes really disheartened: they're not very well educated, and they can be extremely conservative. What we called "the body" was this great, wonderful metaphor for human struggle and all, I think for a lot of them the body is explained third-hand or fourth-hand, on Facebook.

Let's get back to the ICA, and your panel discussion with Karole Armitage and Elizabeth Streb, "The Making of a Choreographer," on Feb. 5. What can we expect? I'm so excited!

Me too! What the devil is that going to be? It's about mentorship and the choreographic process, and I think you're going to get the benefit of three people who are good talkers, who are passionate about what they do, talking about how knowledge is passed from one generation to another. This is a very important topic. I think it's always been a point of pride in the world of dance that one person, communicating something, showed it to someone else. It wasn't like you wrote it down; you had to be there in that space with them. I suspect, that in a world that still has people coming to have a communal experience, to come into a theater and watch live people on stage, it will always be that.

Why is Body Against Body premiering in Boston rather than in your home turf of New York?

They're small-scale works, and they really don't benefit from being seen on large stages, where we normally perform. When we prepared this program, we asked partners across the country who are interested in works that have a historical interest to them, and that, because of the rigor or the demands for an audience, may not be for a broad popular audience, but for, let's say, a museum audience. The ICA has been distinguishing itself as being one of the most adventurous places around the country for this sort of work, and they invited us to come and do it for them.

So what's next?

The company's new works are going in two directions. One is a work I'm calling Storytime. It started out as a way for me to get back onstage, doing what I like to do, which is tell stories. It's inspired by John Cage's famous work Indeterminacy, where I think he tells 90 stories in 90 minutes, with David Tudor performing chance procedures in sound terms parallel to it. I found that so intriguing that I'm writing my own 90 stories. How will my company be integrated into that? That's where the fun starts.

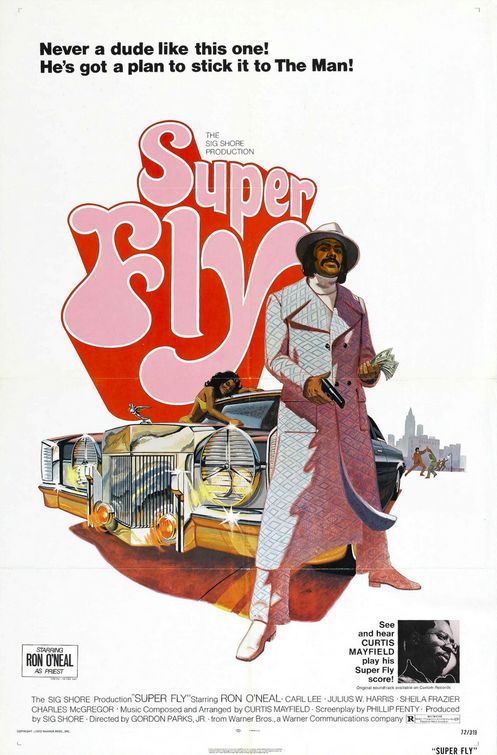

Then there's the new commercial theater work. Which right now we're beginning workshops on. It's based on a 1970s film, set in Harlem... well, no need to be coy about it: it's Super Fly the musical.

Amazing!

I know! I'm just trying to figure out how to give it that kind of spin that keeps it fun and entertaining. How can we take this antihero and spin him? Maybe with the help of some A-list songwriters - they're already getting interested in the project - and with lots of dance in it. Dance that's not just do the hustle, and do the bump, abut that really pushes the envelope the way Fela pushed the envelope around Afrobeat dancing.

When Super Fly came out, weren't you mired in your experimental, minimalist...

Yes! But like everyone, we were fascinated by it. You have to realize: this is not a blaxploitation film like Shaft or Foxy Brown. It's more like an independent art film in the vein of John Cassavetes. It's made by a photographer, Gordon Parks Jr., and it's extremely photographic. Yes, it has its tropes we associate with pimps, hos, drug dealers, and all, but it also has a wonderful score by Curtis Mayfield that was nominated for an Academy Award that year. So there's a lot in it, and we have some high-powered, very adventurous producers as well.

You have a lot going on.

Enough rope to hang myself with. Let's leave it there.

All photos courtesy Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. From top: Bill T. Jones; Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, by Lois Greenfield; from Body Against Body (2); from Fondly Do We Hope; Fervently Do We Pray (2); Super Fly movie poster