Watch the TEDTalk that inspired this post.

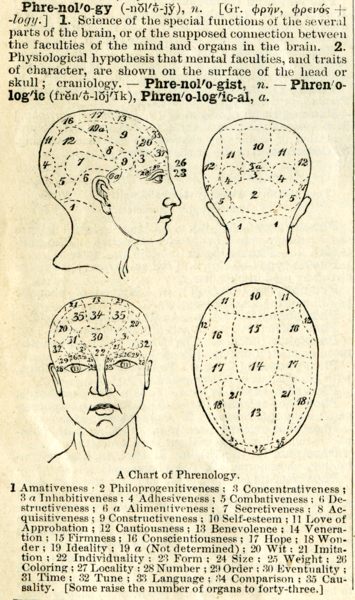

When I trained as a psychiatrist, one of my wisest professors kept on an old wooden filing cabinet in his office a 19th century shiny white ceramic phrenology head. Thick black lines divided the shiny life-sized white skull into over 20 sections, each labeled with a psychological trait -- intelligence, creativity, individuality, secretiveness, combativeness, benevolence, veneration, wonder and hope.

Phrenology, which flourished in the 1820s and 1830s, claimed that bumps on one's head corresponded to these various traits, and could be measured by assessing the size of each bump. The theory was debunked by the middle of the 19th century.

My professor displayed this head to remind us of our hubris in trying to understand the vast complexities of the human mind -- how much we once thought we understood about the brain, and how little we actually grasped.

Photo: Wikimedia

Yet the discussions and debates about whether different parts of the brain are primarily responsible for various mental traits -- and if so, which traits and which parts -- have continued.

A few mental functions have been localized -- most famously Wernicke's and Broca's areas involved in understanding and using language. But recent functional magnetic imaging (fMRI) research suggests that for most other complex mental tasks, the brain is far more integrative -- working as a whole, involving numerous parts and networks.

Still, myths have continued -- including those concerning differences between the right and left side of the brain.

Jill Bolte Taylor's talk, "My Stroke of Insight," raises several of these issues anew.

Her story is powerful and moving. It is terrible that she had to suffer a stroke; and wonderful that she has recovered, and has sought to inspire others.

As I described in my book, When Doctors Become Patients, professionals in health care and research, when becoming patients themselves, often have important lessons to teach the rest of us, as they can see their experiences with unique "double lenses" -- as both patients, and scientists or clinicians. Her vivid description of the deficits caused by her stroke should make us all understand more fully the challenges that millions of Americans face following strokes or other neurological symptoms.

I agree with her that we need to engage with each other more fully, and seek happiness and peace. I do not question her experiences of what she endured.

But her explanations of the differences between the right and left sides of the brain are inaccurate, and promote several myths.

She suggests that that the right hemisphere puts us in touch with "the life force power of the universe", and that to find peace and Nirvana, we should choose to move away from our left hemisphere, with its focus on the single individual, and listen to the "deep inner peace" of the right hemisphere.

If only it were that easy.

In the 1960s, Michael Gazzaniga and Roger Sperry studied patients in whom surgeons had cut certain connections between the two parts of the brain to try to reduce epileptic seizures. This research suggested that in these patients, each hemisphere might then come to specialize in different tasks.

Thus, the right brain soon became romanticized as the seat of creativity and freedom, as opposed to the "logical", "analytical" and constraining left side. Individuals and whole societies have been described as being more or less right or left brained. New Age, self-help gurus have claimed to help people develop the right sides of their brains.

Yet recent fMRI research, illustrating the far vaster integrative complexities of the brain as a whole, remind us how little we know.

For normal brains, in which surgeons have not cut those crucial connections, the two sides work closely together.

Still, the notion that parts of the brain are responsible for certain traits continues to have a certain allure. In part, we have entered an age of neuromythology, and neuroessentialism -- in which we look for "brain explanations" of complex mental phenomena. In the past, many people invoked theories from astrology to Sigmund Freud to explain, and often try to resolve psychological problems. Now, notions of right brain and left brain seemingly make sense of certain human conflicts and difficulties, providing ready explanations for traits that we like or don't like in ourselves or others. Our brains or large parts of our brains -- not we ourselves -- are somehow responsible.

Yet simplifying the brain in this way into simple binaries -- with one half implicitly better than the other -- ignores critical intricacies, challenges and unknowns, doing ourselves, and our brains a disservice.

Perhaps Nature's most complex and sophisticated creation, the human brain is filled with mysteries that should inspire us all, and can lead to better understandings and treatments for a wide range of mental problems.

I wish we could all reach Nirvana simply by turning off one side of our brain; but the reality is far more complex. We cannot shut off half our brain -- nor should we try to. Rather, it is important to understand the inherent tensions, uncertainties and puzzles of human existence, and of relationships between ourselves and others. Humans evolved with competing desires -- not just togetherness and love, but jealousy, ambition, and protection of kin over strangers, etc.

We should pursue the ends she advocates of greater peace and togetherness, but be careful not to oversimplify the brain and ignore science. We will best meet her worthy goals if we recognize, accept and learn how to confront the competing daily pressures that make these ideals difficult.

As we enter the 21st century, 19th century phrenology heads have much to teach us about how much we think we know about the brain, and how careful we need to be.

Ideas are not set in stone. When exposed to thoughtful people, they morph and adapt into their most potent form. TEDWeekends will highlight some of today's most intriguing ideas and allow them to develop in real time through your voice! Tweet #TEDWeekends to share your perspective or email tedweekends@huffingtonpost.com to learn about future weekend's ideas to contribute as a writer.