As the June 12 World Cup edges dangerously close, all heads have turned to its host country, Brazil, in anticipation of an atmosphere of extravagance, excitement and enticement. With expectations running high, is Brazil prepared to take on the burden and honor of the 2014 World Cup, or has it set itself up for disappointment and chaos?

Sluggish construction pace

With less than two months to go, construction workers are frantically putting the last touches on several stadiums and airports, while others stand little chance of being finished before the opening ceremony. A reason for delays can be linked to FIFA's demands to increase the venues from eight to 12, due to the domestic political situation in Brazil.

And it is the Brazilian government that is bearing the grunt of this requirement, meaning more stadiums will be built from scratch with public funds that would have been better used for public service works and durable infrastructure. Moreover, stadiums built in locations such as Brasilia and Manaus will only be used several times during the Cup only to be later abandoned. FIFA President Sepp Blatter expressed deep dissatisfaction with the project, claiming that local authorities were to blame for failing to start work on the projects and stadiums sooner and called it "the most delayed world cup [ ] seen at FIFA."

All these delays come with a hefty price tag. While the initial bid for the Brazil World Cup stood at $1 billion, this has since risen to over $8 billion. It all adds up to $62 million per each football match, a staggering sum for a country that lacks basic infrastructure and suffers from poor public services. Back in 2007, then-president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva promised that private companies would largely fund the World Cup projects. However, it is now evident that the government's public purse is footing the large portion of the bill, fueling public anger and resentment towards FIFA. For example, lavish spending on stadiums has caused many to advocate for "hospitals and schools in FIFA standards."

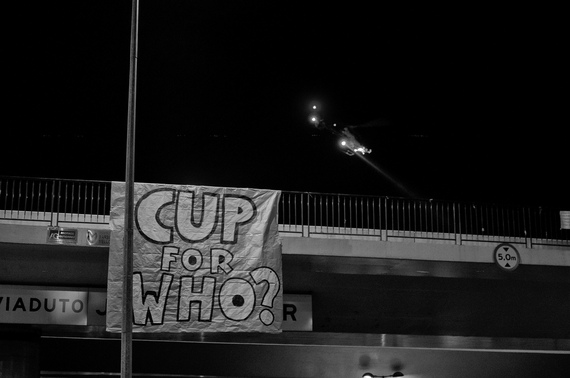

"We don't need the World Cup"

For an event of great stature and pride, the expected violence and protests in Brazil are likely to put a damper on the event. The population, angered by the inadequacy of public services, and flashy investments in one-time extravagant stadiums, are certainly not enthused to host the event. Support for hosting the World Cup stands at a measly 52 percent, rather sad for a country that prides itself on being "the kingpin of FIFA world cup soccer."

Angered mobs of Brazilians, few of whom can even afford tickets to the overpriced event, will likely pose a security threat around the stadiums, as was witnessed during the Confederation Cup of June 2013. During the event, rising bus prices forced millions onto the street to fight for improved public services and shout against the government's pricey upgrades for the World Cup.

Indeed, many of the infrastructure projects -- such as the light-rail system -- that were meant to bring long-term benefits to Brazil's hosting cities have been neglected in a last-ditch attempt to get prime infrastructure for the events completed. Transportation delays, already common in Brazil, will likely increase in the wake of 600,000 expected tourists on top of the 3 million local visitors, causing further security disruptions.

The hefty media presence at the event will mean greater exposure for protestors and their demands. The government, well aware of this potential negative backlash has made contingency plans, but security is likely to be stretched thin. For starters, the Pacification program launched in 2010 has been successful in taking back almost 38 "favelas" (slums) from guerilla groups and drug traffickers and placing them under the protection of community police forces.

In preparation for the events, the government has authorized 150,000 trained professionals from the armed forces to patrol the more troublesome neighborhoods. However, given complaints of police brutality and human rights abuses, the presence of security professionals in the favelas will likely spark more outrage from its residents. Despite the Brazilian government's assertions that, "the World Cup in Brazil will be the safest" on record, recent violent outbreaks between gangsters and police strongly undermine this statement.

Efforts to "pacify" these neighborhoods have for the most part been welcomed by local communities tired of the favela fighting. But while the project has turned some of these slums into safer neighborhoods, violence and protests continue. Local drug traffickers continue attempts to gain back territory from police forces, while others protest continued water shortages, lack of sewage systems, and social infrastructure that the program failed to follow up on.

Big price to pay

With all this money spent and chaos seamed, what will Brazil be getting in return? In the long term, not a whole lot. While the World Cup does create a standing legacy for the Latin American country, its economic benefits are often exaggerated. Jobs that will be created in its wake will likely remain on a non-permanent basis and will only be concentrated in those cities where the games are to take place.

It is not surprising that the support for the event is so low. When the games will be over and the tourists will have scattered, instead of new hospitals, Brazil's cities will be left with useless first-class stadiums, some of which will never see a football match again.

These problems have a global significance and point to a troubling trend in the organization of mega-scale events such as the World Cup and the Olympics. Despite bringing reputation and glory, these competitions often put a great financial burden on the host country, while striving to meet the excessively flamboyant requirement of the committees. Brazil, like many others in the past, will pay a big price for its hosting of the World Cup this year and the Olympics in 2016.

In their book, Soccernomics, Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski argue that the Brazilian World Cup will likely see wealth transferred from Brazil to a number of interest groups such as football clubs and private companies. Taxpayers will see their hard-earned reals awarded to special interests within and outside the country, rather than to the population and the country's long-term development. In this sense, "Brazil is sacrificing a little bit of its future to host the World Cup."