I work with a number of amazing people at Fuller Seminary, one of whom is Dr. Tommy Givens.

Because of my role as a professor of theology and culture, I teach and often write about the interlacing of film, theology, and culture.

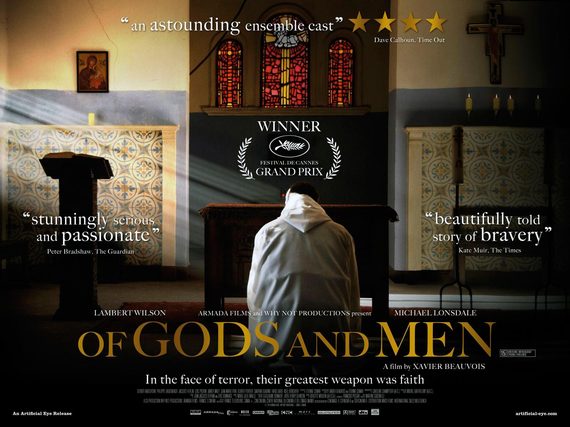

But today I want to highlight my colleague's trenchant analysis of the film Of Gods and Men, in part because we are in the midst of the Christmas season, but also because of the ways in which this movie invites us all to reconsider our approach to violence, terrorism, and the economy in light of Christmas.

In a fraught time such as this -- when certain politicians are suggesting we ban Muslims from the country, when others are willing to accept the collateral damage of carpet-bombing "terrorist" strongholds as long as it keeps us "safe," and when evangelical Christians are being suspended from their jobs by standing in solidarity with Muslim brothers and sisters -- I can't think of a more urgent reminder.

Below is an excerpt from Dr. Given's article, the entirety of which be found on Fuller's Reel Spirituality site.

"Christmas, Violence, and the Economy"

by Tommy GivensChristmas Eve is different from other nights. In the film, Of Gods and Men, it is the decisive night. The Trappist monks of the Monastère de l'Atlas, nestled atop a mountainside Algerian village named Tibhirine, find themselves confronted on that night both by "terrorists" and by the newborn Jesus.

Amidst increasing hostilities in the region, revolutionary fighters have come into the monastery, brandishing assault rifles, to forcibly take Brother Luc to tend to their wounded an hour away. An ailing man himself, Luc is the only doctor in the area. Christian de Chergé, the elected head of the monastery, who has already refused the existing government's military protection and now refuses the presence of revolutionary weapons inside the monastery, further refuses to send Brother Luc or any of the monastery's scarce medical supplies with the armed men. They may bring their wounded to the town clinic, where they will be served without prejudice, as are the rest of the sick.

Ali Fayattia, the head of the armed group, is obviously moved by the nonviolent firmness of Christian, who, having led him outside the monastery walls, appeals to the monks' well-known modesty and quotes a passage from the Qu'ran about the respect due Christian people, particularly monks and priests, "who wax not proud." Their humble conditions are their defense. Finishing the quotation himself from memory, Fayattia relents, and the confrontation appears to end when he summons his troops to leave. But then Christian calls out awkwardly, "Tonight is different from other nights." "Why?" asks Fayattia. "It's Christmas," Christian replies, "We celebrate the birth of the Prince of peace, Sidna Aissa." "Jesus," translates Fayattia, and with that name, the confrontation ends, Fayattia extending his hand and Christian, haltingly, shaking it. A short while later, according to custom, the monks celebrate the Christmas Vigil and Mass.

...

Here it becomes clear not only that Christmas night is different from other nights but that all other days and nights are different because of Christmas night. Being confronted by violent men within the walls of their monastery had brought the monks face-to-face with the limit of their lives, all but paralyzing them with the presence of death, and so all they had left to do was live. And to begin to live in the face of death was simply to observe the calendar determined by the coming of Christ, to sing the words that had long been ingrained in their lives so that now they were sung by sheer inertia. But what they found in that liturgical moment was not the escapist crutch of mere repetition or familiarity, but testimony to the Prince of peace in the very same violent world in which the monks found themselves. The way that the Lord Jesus was born, with threat hanging heavily over his life at its most vulnerable were the power and the promise of life in days of similar danger at the Monastère de l'Atlas.

...

In the coming days, our society will, once again, invoke Christmas to pretend that we are Christian. We will sound a hollow profession that Christmas night is different from other nights. For the Messiah child, absolutely helpless and already so threatened, we will substitute the slicked-out, Disneyified Jesus of commerce, the gnostic icon of a culture addicted to sanctimonious self-gratification that is as superficial as it is savage. There will appear to be nothing helpless or threatened about this Jesus, who is charged instead with solemnly reassuring us that our ostensibly abundant life is sacred and secure.

And then we will watch as the self-righteous brokers of this culture skirmish over the extent to which this sort of Christmas should yield to more "inclusive" displays of Happy Holidays. We will listen as market speculators celebrate the contribution of Christmas greed to "the economy." And our eyes and ears will be flooded with scenes of Christmas charity that serve to justify our violence and exploitation as the work of generous people. We can scarcely imagine the price that so many must pay for our capitalist religion, whose sparkle is the Christmas Holi-Day. Nor can we imagine what this religion does to us who are its purveyors, who know so little of worshipful work. The prophet cries out against us:

"Trample my courts no more; bringing offerings is futile; incense is an abomination to me. New moon and sabbath and calling of convocation--I cannot endure solemn assemblies with iniquity. Your new moons and your appointed festivals my soul hates; they have become a burden to me. I am weary of bearing them. When you stretch out your hands, I will hide my eyes from you; even though you make many prayers, I will not listen; your hands are full of blood." (Isaiah 1:12-15)

We, too, have to resist the violence. But can we? By what rhythms do we live if their culmination is the American Christmas? How can we possibly manage the manifold refusal that Christian managed when, day after day and year after year, we say yes to "the economy" which preys systemically upon so much of the earth's people, animals, plants, water, and soil, all in the name of "growth"? The way that Christmas toys are made in China is but a single tooth in an omnivorous machine that never turns off. It is fed by an exploitive and oppressive relationship to the people and lands of the Middle East, one that sows bitterness that is being reaped and will continue to be. Being consumed by this machine, how can we live up to the night that is different from other nights? How can we celebrate the birth of the Prince of peace?

We might despair, but one of the reasons Of Gods and Men is such a true movie is that it shows the agonizing strain of Christian nonviolence. Christian de Chergé can be seen time and again pacing and wringing his hands, his face twisted with conflicting impulses in the face of new tragedies, his fellow monks torn between insufferable alternatives. There is no easy road to peace, and there are no short-cuts for us from a culture of violent consumption to Christian holiness.