When Clayton Raithel's first encounter with love came to an unexpected end, he suffered far more than just a broken heart. What looked like an average college breakup spiraled into a major depressive episode, complete with panic attacks, sobbing sessions, psychotherapy and a Zoloft prescription. But in time he found relief in an unlikely place -- the stage on which he stood for his stand-up comedy routines.

While there's no scientific consensus on the potential link between depression and comedic expression, there's no denying that some of the world's most beloved comedians suffer or have suffered from mental illness. Jim Carrey has struggled with bipolar disorder. Daniel Tosh has struggled with social anxiety disorder. And while he had never been formally diagnosed, the late Robin Williams has mentioned his struggle with severe depression (as has his publicist following Williams' death).

A 2014 study of 523 comedians found that they exhibited high levels of psychotic personality traits common in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Those same characteristics have also been credited with making these people so creative. And for comedians like Raithel, comedy serves as a crucial form of expression for his mental illness. The stage allowed him time and space to process what was happening to him in a way he couldn't with therapy and self-help alone. "Smile," his new autobiographical, one-man comedy show, is the direct result of this processing.

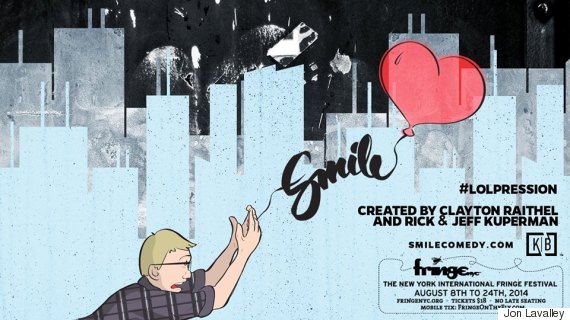

Artwork from "Smile," Raithel's one-man show that debuted at the 2014 Fringe Festival

Up until his breakup, Raithel was the picture of a highly successful northeastern adolescent. He grew up comfortably in the suburbs of Boston and attended Princeton University. While he experienced social anxiety when speaking with female peers, he still found himself dating Chelsea -- the only girl he's fallen in love with -- in college. When it ended, he thought he was just experiencing the normal melancholy of processing that grief. It took time, finishing college and moving to New York for him to realize that it was something more.

"I didn’t really start feeling what would be later classified as major depression until I graduated," Raithel, 25, told The Huffington Post. "When I went to therapy, I gradually realized that it was much more than that. It really was that my brain was exhibiting what psychologists would call maladaptive thought patterns. I found myself really in the throes of it for about two years. At various points in those two years, I got very low, then I thought I was settled, then I would have a version of a relapse."

He saw a psychologist as well as a psychiatrist. He was prescribed Zoloft as part of his treatment. He worked odd jobs -- as so many newcomers to the city do -- while attending improv comedy classes. Having been a member of two student comedy clubs at Princeton, Raithel knew it was a talent he wanted to pursue. It proved to be one of the few things that could keep him grounded in the next phase of his life.

"I distinctly remember having this one moment where I got a big laugh in one of my classes, and then all of a sudden, everything felt fine for like 10 seconds," he recalled. "It felt almost cheap when it first happened. I thought to myself, ‘Am I really only going to be happy if people are laughing at the jokes I make in an improv class?’ because that seemed problematic, too. But in the moment, I was like, ‘Well I’ll take it! I’ll take feeling normal for a little bit.’"

Despite these moments, Raithel still found himself complaining about his life constantly to friends and family -- to the point where he was driving them away and feeling more isolated than ever. During a visit home, he went to see the film "Les Miserables" with some friends but a panic attack caused him to miss most of the film. When he later joked about how many "plot holes" the movie had (due to his vomit-induced absence), everyone laughed.

"In that moment, I realized that maybe this is one of the ways that I can sort of process this," he said. "Maybe this is one of the ways I can get people inside my mind -- use humor."

A few months later, he saw comedian Mike Birbiglia’s one-man show "Sleepwalk With Me," which chronicles his struggle with anxiety and rapid eye movement behavior disorder. He watched Birbiglia take uncomfortable experiences and share them in an amusing way that not only helped him deal, but also gave his audience something real to relate to. Raithel decided he wanted to do something similar.

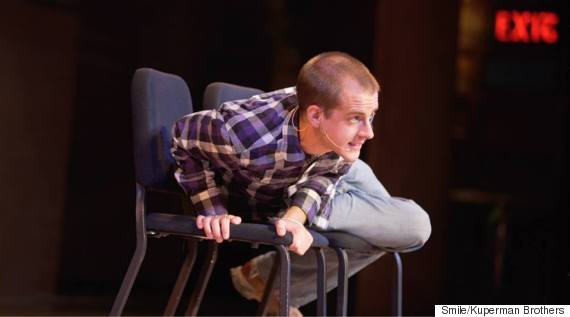

Raithel workshopping "Smile," his one-man-show

He began writing "Smile" in the fall of 2013. He was still struggling with his major depressive episode, and it felt cathartic to be able to work through his thoughts and emotions with this project. By early 2014, the first draft was ready. After months of workshopping, he presented "Smile" at the Fringe Festival in New York in August 2014, and filmed it at his old stomping grounds at Princeton two months later.

Watch Raithel's full "Smile" performance at Princeton University here.

"Now I feel much more comfortable just letting it be part of my catalogue of material."

In "Smile," Raithel neither belittles nor makes fun of depression, but shares his experience in a self-deprecating way. He is the butt of his own jokes -- both the protagonist and antagonist. By allowing himself and others to laugh at his pain, he hopes to convey that it's also acceptable to talk about these feelings, reducing the stigma that has long accompanied mental illnesses in our society.

Raithel in the middle of his performance of "Smile" at Princeton University

"I could tell within the first five minutes of a performance whether this was an audience that was going to be okay with laughing at what I was going to talk about," he said. "I have a joke about suicide pretty near the beginning of the show and I can feel the audience when they’re uncomfortable with that. I can see it in their eyes... I had days where I did the show and it felt more like a drama than a comedy, but people still come up to me after and have very positive things to say about the show."

Traditional psychotherapy also played a role in bringing Raithel's show to light, he said. By working with a professional whom he respected and admired -- and who challenged him -- he was able to look inward and process the coming-of-age trauma he was experiencing. This introspection created some distance between him and what ultimately became the material of his comedic routine, Raithel said. If he hadn't put in the work in therapy, he believes he wouldn't have found the comfort to laugh so genuinely at his own struggle.

"People have argued that it’s a defense mechanism of some type, and I don’t know if I agree with that," he said. "I think it’s a coping mechanism in that it does help. But at the same time, it's a therapeutic move. I felt when I was writing the show that I was doing a lot of the things I did in therapy. I was asking myself why I felt this way at that moment, and then why is that funny. It’s a similar question to, 'Why are you feeling sad today?' Those questions force you to look inside yourself."

It also has an advantage traditional therapy doesn't.

"Realizing on stage that other people deal with that, too, or at least appreciate it, there’s therapy in just knowing there are other people out there who can validate your experience," he added.

Raithel recently finished his nursing degree in New York City, channeling a lifelong passion for taking care of others. Nursing provides fairly flexible work hours and he will continue pursuing comedy. He is no longer seeing a therapist, no longer taking medication and feels the most stable he has in years. His experience with depression might not have been that lifelong narrative that so many others live, but he still hopes his work can give others the courage to talk more candidly about what mental illness feels like and ultimately help those affected begin to recover.