Everything that follows results from one very incomplete perspective of the poet Max Ritvo. I was his friend, but I do not know everything, or even much, of what there is to know about him.

--

Max lived at the hectic pace of someone running out of time. He hacked away as much of the trivia of normal life as he knew how. He did not become friends with me as one ordinarily develops a friendship: he took a liking to me and then immediately took a position of "I love you." He committed to his propositions without reservation. He was living without consequence, because he wasn't going to be burned later for his errors. Instead of walking away, I said, "I love you back," and the love filled itself in afterward. Max was a very funny guy and saw the humor in everything. He knew his arrangement with me was faintly absurd. But he had no choice about it. Life, which is absurd for everyone, was especially absurd for him.

Max had Ewing's Sarcoma, an especially vicious cancer. It lives in the bone marrow and eventually contaminates the entire body. There are few adults with Ewing's Sarcoma because it kills most of its victims as children. Max's case emerged when he was a teenager, so his adult personality formed in the shadow of short time. He was not somebody whose long life was going to be cut short. He understood himself as an organism designed not to last long. Of course he wanted to live, but he knew that he probably wouldn't. He was 25 when he died this August.

--

I met Max because I was friends with Melissa Carroll, a painter who had the same disease. At Melissa's wake, I happened to be sitting right behind Max. He was very close with her, and his fleshless shoulders were shaking with his sobs. I barely knew him. In a panic, I put a tentative hand on his shoulder. His friends saw the seating error that was unfolding, and came and replaced me. Sometime after that, we became friends.

Max was a poet and an essayist. I curated an issue of the magazine Poets/Artists, and I put a spectacular late painting of Melissa's on the cover. I asked if I could run his poem about her, "To the Hands of My Painter," in the same issue. He gave me permission. Here is a piece of that poem:

When you go to the earth

the last part of you visible

above what is either sand or clay--

I don't know which because either everything is water

or nothing is water--

will be your hands.

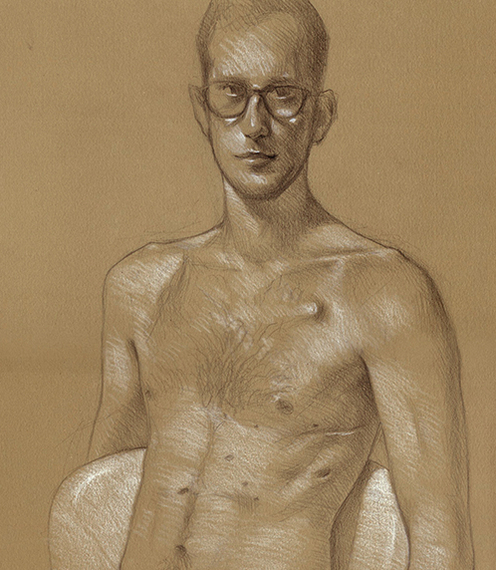

Reading it again now, it brings back the sharp grief of Melissa's passing, and I suddenly remember, with some shame, a half-submerged feeling I had when I first read his poem. I was envious. I'm a painter too, and I was envious that Melissa had somebody who could write like that, and wrote like that about her. But Max wanted to come sit for me, and I drew him and painted him, and he wrote a gorgeous forward for a book of drawings I have coming out next year, so he healed my embarrassing wound.

Max had no qualms about nudity for art because his condition deprived him of privacy in general. He was always getting naked for somebody or other. Plus he was a bit of an exhibitionist. After our first drawing session, we talked about the impressions we'd formed of one another. I told him he was much more of a dude than I would have anticipated for somebody who seemed so fragile. This delighted him. He was an athlete before illness interfered, and I think he would happily have spent time being one of the guys. Perhaps he did. I had a very narrow window on his life.

We went to sushi after that drawing session. It was a thoughtless suggestion on my part. He was tired and he couldn't eat. But he relished my pleasure in the sushi. I recognized that relishing - it's what people who can no longer enjoy some physical sensation do when they have developed the mental discipline to take nearly as much pleasure in its contemplation, or in the happiness of their friends.

--

I don't really like much poetry, but I like Max's work. His English is crisp and clear, even when his images are demented and ultimately indecipherable. He applies a vast knowledge of the western canon to his work, but he is not especially solemn about it. I don't think he was solemn about much of anything. He valued laughter very much. He said funny things in a funny hoarse barking voice, he dressed in funny clothes, and he often took on a comical aspect in his movement. If he hadn't flung himself around in a jerky silent-film-comedian style, you'd have seen he couldn't move normally either. He was in pain and his body was failing. So he made a cartoon out of his motion. This stands well for other humorous aspects of his presentation. They covered his pain and they disrespected it. He couldn't defeat death directly, but he could certainly deny it the respect it demanded. Disrespect was of crucial importance to Max. Nature itself, as Camille Paglia notes, is capable of fascism. Max faced fascist nature his entire life, and like many intellectuals, he treasured disrespect and mockery in his arsenal of resistance.

--

I spoke on the phone with Max sometimes, and texted with him quite a lot. He was often angry and depressed. By the time I got to know him, he was near the end. He didn't want to die and he was scared of dying. But I think you get used even to the overbearing presence of fear, and become aware of it again only when your enemy has suddenly leapt another giant pace forward. I couldn't do anything for him, except be his friend, and not pretend it was going to be OK. I have a toddler, and my toddler loves to go on swings. I would take pictures of my toddler smiling ecstatically on swings under spring and summer light, and text them to Max, because he liked to see my toddler growing up and being happy, and because I heard somewhere that looking at pictures of children has some health benefits. Now I think of Max when I take my toddler swinging. I knew I'd go on thinking of him at those times even after the cancer finally got him, and that's alright, because the living carry the dead. It can be a burden, but it is also a joy, just like raising children.

I actually haven't finished my painting of Max. The left arm is missing, waiting on him to come sit again, and the background is undone - he wanted it to be adapted from a wildly colored painting Picasso did of his studio. I haven't read a lot of Max's essays or poetry either. I was putting off all these things. In 1974, when film director Werner Herzog heard that his friend Lotte Eisner was dying in Paris, he walked to her from Munich, convinced she couldn't die until he got there. I had some similar idea about the painting and the writing, but Max went ahead and died anyway.

--

One afternoon while Max was lying sick in California I was dozing in Brooklyn, and dreaming about Max dying. In the dream, life was played out in a cartoonishly bright and happy meadow surrounded by forest. There was a single break in the trees, but it was a break in the blue summer sky as well. It was a flat region of eye-curling nothing. This was death. One might trip toward it, and fall into it, and then one would simply be gone, into that hideously convoluting non-color. Max was going out that corner of life's meadow.

I told him about this dream, which quite tickled him. He was an unruly materialist and insisted that once this life got done, there wasn't anything else. He said, "When my jelly and electricity don't work anymore, I'll be glad to continue being a pattern in yours." Jelly was an important word for him, to describe the uncertain substance of the body. In this case he meant the brain. Personhood arose in the brain and when the brain stopped functioning - stopped forming electrical patterns - personhood as a first-person experience, any form of "I," ended. This was Max's doctrine.

--

This radical doctrine, not only denying God but also denying the real existence of any spiritual phenomenon separate from matter, is kind of a young man's doctrine. It's the sort of thing that's easiest to believe when you feel death to be quite far off and not your problem. Max, obviously, did not feel that way at all, but he stuck with the doctrine. The closer one draws to death, the costlier this doctrine becomes, until finally it is overwhelmingly heavy to carry. But in my conversations with Max, he never swerved from it.

He did not swerve from it, but he still had to solve the problem of living and hoping in the face of his fate. He took a number of strategies. He lived fully and well, completing his education, taking responsibility for his art and producing a great deal of it, laying plans for teaching, and marrying his longtime sweetheart Victoria. I met her at a late-evening get-together Max threw for his friends at a former speakeasy in lower Manhattan. Max was pretty sick, and the gathering probably had the feeling of that first Easter: all the friends celebrating again with Him, joyously, poignantly together one last time, after they thought their time together was done. I got tired and went home before Max did.

Victoria, a psychology student, and her brother David, a math whiz, were adorable. Max and Victoria's marriage reminds me of one of the few effective passages in the mediocre movie Deep Impact. In this snooze of a film, a meteor is going to incinerate Earth's surface, and the government has built some deep bunkers that are going to save a select group of people. One young teenager is on the saved list; his girlfriend isn't. But spouses of the saved get to be saved too. So these kids get married, even though they're maybe thirteen. The ceremony is a solemn simulacrum of an adult marriage, an uncanny symbol of apocalypse. Max and Victoria felt like that to me. They would have gotten married anyway, but they had to get it done prematurely, because the end was in sight. She's a widow now, in her mid-twenties, and I haven't asked her, but I bet she wouldn't have traded a minute of it for the world. The world decides how much time you get; your job is to live well with whatever you're allowed. The two of them did right by life and each other.

Then there is Max's other strategy. It is like that of the sick child in Robert Louis Stevenson's "The Land of Counterpane":

When I was sick and lay a-bed,

I had two pillows at my head,

And all my toys beside me lay,

To keep me happy all the day.

And sometimes for an hour or so

I watched my leaden soldiers go,

With different uniforms and drills,

Among the bed-clothes, through the hills;

And sometimes sent my ships in fleets

All up and down among the sheets;

Or brought my trees and houses out,

And planted cities all about.

I was the giant great and still

That sits upon the pillow-hill,

And sees before him, dale and plain,

The pleasant land of counterpane.

This is the same strategy that Frida Kahlo pursued from her own sickbed, and Shakespeare's Richard II in his prison cell at Pomfret Castle - "I have been studying how I may compare/This prison where I live unto the world..." - and Nelson Mandela at Robben Island, and which all wise prisoners take, who discover that freedom is not measured in range of movement or variety of diversion - but in the self-government and liberation of the soul.

Each prisoner who joins this ancient and profound tradition discovers the right manner in which to free himself. For Max, it was through the essays he wrote in his final months. These serve as the "and yet, and yet" to the austerity of his materialism. And yet: this materialist became one of the great surveyors of the interior, one of the great analysts of the real existence and complex progression of the subjective. On the one hand, locked in his body, he could do little but introspect. But on the other hand, his charting of himself as mind, personality, and spirit seems to me to stand in rebuke to his own stated philosophy. It is not a direct logical rebuttal, because it nowhere posits the independent existence of the soul. And yet in its insistence on the primacy and reality of the vast inland, it is inconsistent in tone with his just-the-neurotransmitters-ma'am hardbitten minimalism:

"I have a strange feeling right now, that I'd like very much to make an Elemental Cosmology. That it'd unlock secrets about me. But I have too much common sense for that project. Threading the metaphor backwards, however, I have firm proof of my emotions, and much evidence that they transmute, like fire, and water, and weather. So, more reasonably, I could try to find out what my first Emotional Element is.

...

But I'm not even as interested in knowing What Emotion Came First, as I am in making sure a particular emotion didn't come first. I want to know, in my heart of hearts, that my first Emotional Element is not rage.

...

Let the first element be Panic, and not Rage. For the Greeks, the family was the pervasive metaphor that governed the seasons, the gods, and blood and bile. So to discover the elements like a Greek, I want to tell stories about Families.

...

This is the story of how Panic falls in love with her true love, Violence, and they give birth to Rage.

My whole life I have lived with no appetite, a quick-beating heart, and dilated pupils. These are all symptoms of panic, what my father refers to as 'the Old Fight and Flight' response. Panic floods the body with a cocktail of adrenaline, cortisol, and epinephrine, causing these symptoms. Your body fizzes with electricity, which is what your thoughts are made of, and you feel your thoughts across your whole body. This is not rage.

I think panic becomes rage when you're exposed to violence, like electricity that becomes fire when you introduce logs. Your body learns this is what to do with the panic. But I think my mom was being over-protective--my wife watched The Terminator as a child, and isn't violent at all. It's not about what you see, it's about your muscles hurting and being hurt. You have to feel pain, or feel your body harm another to have the epiphany of becoming violent."

This is from the essay "Mortal Kombat," published January 16 of this year in Berfrois. In this excerpt, we see many of Max's qualities as a writer: his sardonic voice, his clarity of speech, the classical liberal education which informed his thinking - his effortless leap from current psychological and neurochemical models of the interior to outright alchemy, which is to say, magic - and, by my lights, the empathetic spiritual light in which he taught himself to see things. In teaching himself to overcome his self-loathing and self-terror, he accidentally learned to love people in general, taking the good and the bad in them with the equanimity of someone who has no horse left in the race of life and its agonies; leaving only the quiet pleasure of a sage in witnessing the pageant of humanity still unfolding, so foolish and so full of noble hopes.

I can hardly believe that Max is gone, and cannot stand it. I have been reading his poems this evening - poems I put off while he was alive - and I am stunned I cannot write to him and tell him I liked this bit or that -

But I wasn't alive--

I was the ghost in the bridge

willing the cars to join me,

telling them that death was not wind,

was not weight,

was not mist,

(from "Earthquake Country Before Final Chemotherapy," published in Parnassus)

I understand that my spiritualist take on Max's perspective may represent my own concerns much more than his. Max joked about death, and ran toward it as much as he ran from it, and argued to the end that beyond it there was no awareness. Perhaps I should respect his dignity and leave it at that. But on the off chance that his materialism was another middle finger he flashed at ravenous death, and that if the fear had not been so terrible for him, he would have entertained hope - let me be the square who argues that there is room in his dark ideology for the soul, having slipped off the soiled remains of the body, to breathe a clean breath and makes its way along in a vast and healthy universe. It is absurd to think that one can save him with these weak arguments, but they are of a kind with the rituals we assign ourselves for disposing of the dead. We hope they will console the dead, but they are essential for those who must carry on. I can't bear to have Max dissipated away, as I could not bear Melissa before him. Their lives here were crackling, fatally damaged intervals between one infinity and another. In that, they were like us, but more so.

Therefore let me send you on your way with love, Max. If it is silence, then it is silence. If there is sound, there is sound with me or without me. But if my faith can make any difference in your journey, then I will never stop offering it.

--

Addendum: Max's mother, Ariella, in reviewing this essay with me, notes that Max was a Buddhist, with a model of God as universal love. Who knew? He never told me such a thing. He presented himself to me in one way, and to other people in other ways. Berfrois has a memorial to Max up now, written by his family and friends. I haven't read it yet, because I want to hold on to my idea of Max, as he wanted or needed me to see him, long enough to get these notes done. But if you'd like to hear Max's voice, very close to death but full of wit and life, listen to his second interview with Dr. Drew. In this interview, he discusses the role of love in his life - the enormous role of love in his life - much as Ariella describes it. As you listen, note how he starts the interview with a weak voice and a tired and confused state of mind. The more he speaks, the more voluble and cheerful he gets. Company and ideas and jokes act for him like water for a plant. He starts out withered, and comes to vibrant life. This transformation is very much as I knew him to be. He should have gone on being like that much, much longer, but he was generous, and shared his sparkling life with as many people as he could in the time that he had; in his writing, he goes on sharing.

--

Four Reincarnations, Max Ritvo's debut collection of poems, is available here:

https://www.amazon.com/Four-Reincarnations-Poems-Max-Ritvo/dp/1571314903/