The Museum of Modern Art, designed by Yoshio Taniguchi. Entrance at 53rd Street. c. 2007 Timothy Hursley

The Museum of Modern Art, designed by Yoshio Taniguchi. Entrance at 53rd Street. c. 2007 Timothy Hursley

The Museum of Modern Art holds a special place in my affections: from the age of sixteen when I was an intern, all the way through college and then after college, the Museum was where I worked, and no less importantly where I played. My bosses were a highly eclectic lot: a future Hollywood mogul, a White Russian expat, a society lady from Southampton and a publishing expert who would eventually become the director. In the days when carbon sets were still the norm, my impoverished typing skills were no calling card; I was much better at filling brown paper bags with sand and candles for opening night parties and flirting with the Italian designers whose work was on display.

(The museum has not incidentally provided me a tutorial in the ways of men, and how much I still have to learn, a lifetime turning out not to be enough to know better.)

But in and amongst the homemade lighting duties and assignations were assignments filing stills from Bergman and Fellini films and photographs by Diane Arbus and putting together complicated exhibition catalogues and these tasks gave me the first real taste of what museums could do--their roles as annointers, archivists, helpmeets, collectors and focal points of cultural life in the community.

Right now, the work of three very different men on display at the museum has a great deal to teach us about art and life and the way we might process the world around us. It's a stimulating thing to be able to able to leap centuries, genres, mediums and point of view amongst Georges Seurat, Lucien Freud and Martin Puryear. One would think, just looking at the art, that there is little to tie them together.

Yet their fierce originality, their fearlessness about not marching in lock step with their peers, all this shines through and unites them as true artists, digesting the world on their own behalf, not ours, yet by owning it so entirely making it completely universal.

The exhibition of drawings of Georges Seurat has a quiet brilliance that perfectly echoes one of the artist's defining features: his self-chosen muteness. In an age where hyperbole often supersedes -- if not substitutes-- for artistic capability, Seurat's grave but not somber drawings and his reputation for reticence comes as a breath of fresh air. And this air is only going to be there until January 6th, and will not travel, so it really is worthwhile making a special trip to see these lovely, technically accomplished images.

(And you know when you are standing on line at the airport waiting to board the plane and complete strangers are talking about an art exhibition 3000 miles away that there must be something very special about it.)

Jodi Hauptman, the lively and accomplished curator had great ambition for this exhibition which is the most important since the big retrospective in Paris in '91 and the only one to concentrate exclusively on the drawings. Over half are from private collections, and half from outside the US. They will not pass this way again soon.

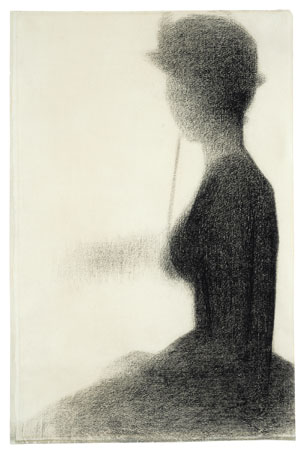

We know about the extraordinary large paintings (e.g. La Grande Jatte) so the complex landscapes are, "a revelation" she says, but my favorites are the portraits. The sculptural hourglass figure of a woman in profile:

Seated Woman with a Parasol (study for A Sunday on La Grande Jatte), c. 1884-85 Conte crayon on paper 18 3/4 x 12 3/8" (47.7 x 31.5 cm) The Art Institute of Chicago. Bequest of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, 1999.7 Photo courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago

Seated Woman with a Parasol (study for A Sunday on La Grande Jatte), c. 1884-85 Conte crayon on paper 18 3/4 x 12 3/8" (47.7 x 31.5 cm) The Art Institute of Chicago. Bequest of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, 1999.7 Photo courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago

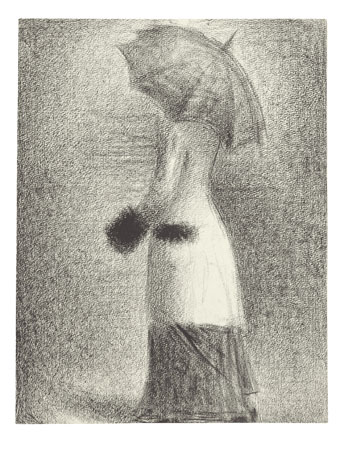

The back of a woman holding a parasol:

The White Coat (Woman with Umbrella), c. 1883 Conte crayon on paper 12 5/16 x 9 3/8" (31.2 x 23.8 cm) Private collection Photo: R. Lorenzson

The White Coat (Woman with Umbrella), c. 1883 Conte crayon on paper 12 5/16 x 9 3/8" (31.2 x 23.8 cm) Private collection Photo: R. Lorenzson

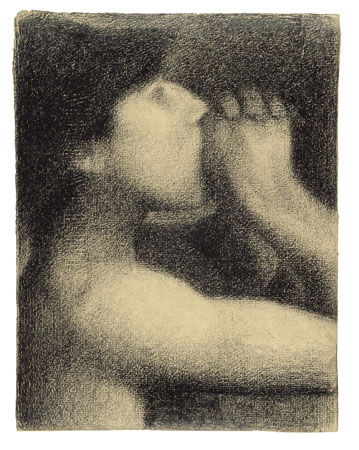

A young man, his hands cupped, as he seemingly tries for an echo:

The Echo (study for Bathing Places, Asnieres), 1883 Conte crayon on paper 12 5/16 x 9 7/16" (31.2 x 24 cm) Yale University Art Gallery, Bequest of Edith Malvina K. Wetmore

The Echo (study for Bathing Places, Asnieres), 1883 Conte crayon on paper 12 5/16 x 9 7/16" (31.2 x 24 cm) Yale University Art Gallery, Bequest of Edith Malvina K. Wetmore

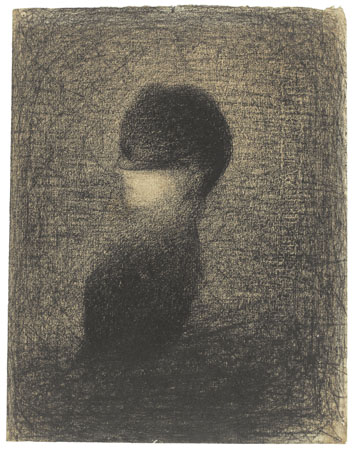

The half-veiled face of a mysterious woman:

The Veil, c. 1882-84 Conte crayon on paper 12 3/8 x 9 1/2" (31.5 x 24.1 cm) Musee d'Orsay, Paris, conserved at the Departement des Arts Graphiques, Musee du Louvre, 1982 c. Reunion des Musees Nationaux / Art Resource

The Veil, c. 1882-84 Conte crayon on paper 12 3/8 x 9 1/2" (31.5 x 24.1 cm) Musee d'Orsay, Paris, conserved at the Departement des Arts Graphiques, Musee du Louvre, 1982 c. Reunion des Musees Nationaux / Art Resource

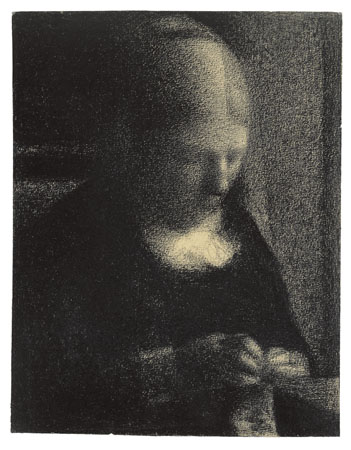

the artist's mother embroidering, the part in her hair head rendered with subtle finesse:

Embroidery (The Artist's Mother), c. 1882-83 Conte crayon on paper 12 5/8 x 9 7/16" (32 x 24 cm)The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1951; acquired from The Museum of Modern Art, Lillie P. Bliss Collection (55.21.1) c. 1989 The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Embroidery (The Artist's Mother), c. 1882-83 Conte crayon on paper 12 5/8 x 9 7/16" (32 x 24 cm)The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1951; acquired from The Museum of Modern Art, Lillie P. Bliss Collection (55.21.1) c. 1989 The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Hauptman stresses the technical aspects of the decade-long mature production: the composition of the conte crayon, the provenance of the paper, the methodical process by which he captured images outside and then worked on them in the studio.

But the mystery of his short life (he died, after a violent three day struggle with diphtheria, at 31) and the spectral halos that magically surround the figures which are often presented from the side or back are what intrigued me. Seurat came from a bourgeois family and had a mistress with whom he had a son but so little is known about them. He had friends among the other painters and would often join them on sketching expeditions, but his view of the world was pixilated--some believe the pointillist dots in the paintings have antecedents in the rough crayon sliding over the hills and valleys of the paper.

There is so little mystery in many of today's most famous painters whose lives are readily available for public consumption. But interestingly, Martin Puryear's work, which is also on view shares a certain quiet reflectiveness , a stand-aloneness that shouts out:

Martin Puryear. Bower. 1980. Sitka spruce and pine. 64" x 7' 10 3/4" x 26 5/8" (162.6 x 240.7 x 67.6 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C. Museum purchase made possible through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, Alexander Calder, Frank Wilbert Stokes, and the Ford Motor Company. Photograph by Richard Barnes. c. 2007 Martin Puryear

Martin Puryear. Bower. 1980. Sitka spruce and pine. 64" x 7' 10 3/4" x 26 5/8" (162.6 x 240.7 x 67.6 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C. Museum purchase made possible through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, Alexander Calder, Frank Wilbert Stokes, and the Ford Motor Company. Photograph by Richard Barnes. c. 2007 Martin Puryear

Puryear came from segregated Washington DC and so access to the National Gallery was special and magical; then in Chicago, the science and natural history museums added to his fascination with exotic objects. He enlisted in the Peace Corps and lived in West Africa among indigenous peoples; here, he began the move towards abstraction and to using local materials. But he has never joined an art movement and cannot imagine being held to one or another political or social idea. He began as a figurative painter but his experiences overseas changed him dramatically, and unlike many artists, he doesn't mind if his work is beautiful--and indeed it is. But in a Seurat-ian echo, he finds the most interesting art has a "flickering quality where opposed ideas can be held in tense coexistence." As Seurat sees the sculpture in the human body, Puryear sees the biomorphic forms in sculpture. Puryear's work has one other subtext which stands out: it feels like he has been thinking about the evanescence of the natural environment--and that in a pinch, we could crawl into one of his bentwood structures and be protected, somehow from the ravages of man, if not nature. This show closes on January 13th.

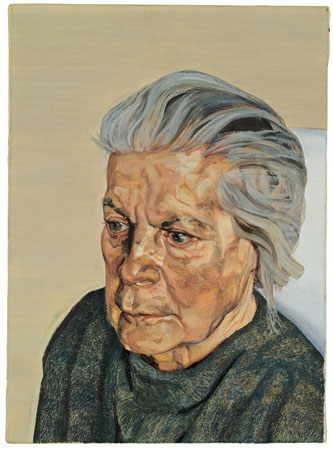

An early practitioner of the merging of the public and private was Lucian Freud--a man for whom the social qualities of work, the incorporation of friends and family into his data base was as natural as getting up in the morning. Freud studies the human form the way Seurat does except Freud comes from the warts and all school--his portraits of his mother:

The Painter's Mother III. 1972 Oil on canvas 12 3/4 x 9 1/4" (32.4 x 23.5 cm) Private collection Photo: Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library 2007 Lucian Freud

The Painter's Mother III. 1972 Oil on canvas 12 3/4 x 9 1/4" (32.4 x 23.5 cm) Private collection Photo: Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library 2007 Lucian Freud

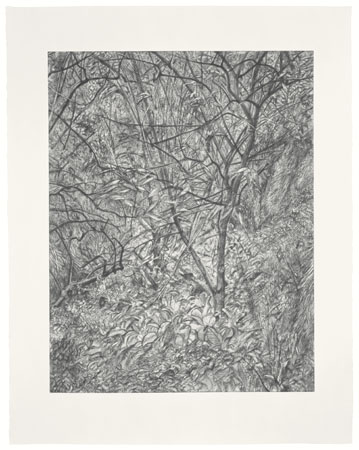

grieving after his father died show her haggard face not her carefully combed hair--he definitely does not care if his models look beautiful. As Seurat uses spiderwebby backgrounds from which the figures emerge, Freud uses an etching plate, bunching, feathering and hatching his way to bring the figures and landscapes into relief.

Garden in Winter. 1997-99 Etching Plate: 30 1/8 x 23 7/16" (76.5 x 59.6 cm) Sheet: 38 3/4 x 30 3/8" (98.4 x 77.2 cm) Publisher: Matthew Marks Gallery, New York Printer: Marc Balakjian at Studio Prints, London Edition: 46 Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York Photo: Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York c. 2007 Lucian Freud

Garden in Winter. 1997-99 Etching Plate: 30 1/8 x 23 7/16" (76.5 x 59.6 cm) Sheet: 38 3/4 x 30 3/8" (98.4 x 77.2 cm) Publisher: Matthew Marks Gallery, New York Printer: Marc Balakjian at Studio Prints, London Edition: 46 Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York Photo: Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York c. 2007 Lucian Freud

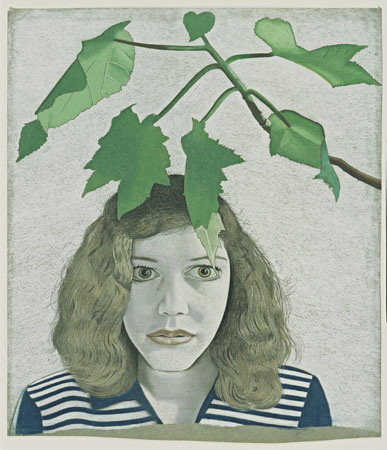

Though the focus of the exhibition is on the drawings and etchings, one's eye is inevitably drawn to the paintings which have always been amongst my favorities: his daughter Bella, an early Girl with Leaves:

Girl with Leaves. 1948 Pastel on gray paper 18 7/8 x 16 1/2" (47.9 x 41.9 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase, 1948 Digital Image Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, Mali Olatunji c. 2007 Lucian Freud

Girl with Leaves. 1948 Pastel on gray paper 18 7/8 x 16 1/2" (47.9 x 41.9 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase, 1948 Digital Image Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, Mali Olatunji c. 2007 Lucian Freud

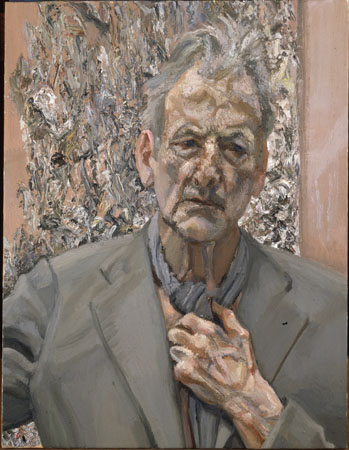

owned by MoMA and a classic self portrait:

Self-Portrait: Reflection. 2002 Oil on canvas 26 x 20" (66 x 50.8 cm) Private Collection Photo: John Riddy c. 2007 Lucian Freud

Self-Portrait: Reflection. 2002 Oil on canvas 26 x 20" (66 x 50.8 cm) Private Collection Photo: John Riddy c. 2007 Lucian Freud

which was an excellent representation of how he looked at the opening. Normally known for abhorring large events where he must work the crowd, at MoMA he was amongst friends and long-time collectors so seemed somewhat at his ease, his long thin scarf substituting for more formal attire.

These three men, seemingly quite different, separated in one case by a century and in the other case by their wildly different backgrounds and their chosen media are joined by this: a willful independence and a totally original way of seeing the world. To tarry at MoMA this month is one of the best presents you can give yourself--you will be inspired and stimulated, and as a holiday bonus, you might learn a little about men and how they think.