The Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Museum, Copenhagen

At the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Museum in Copenhagen, a 19th-21st century pile not far from the Tivoli Gardens, a surprising world of oft overlooked Danish connections to Gauguin--an artist we mistakenly think we know everything about e.g the dramas with Van Gogh, the South Sea "idylls"--unfolds in a quiet but dramatic fashion.

The museum itself was founded and still linked to the Carlsberg brewery fortune and houses an eccentric collection of ancient art, modern French Impressionism and Danish Golden Age--a wealthy, embattled family's varying predilections for salon art mingled with the shock of the new. Four distinct pavilions come together in a crystal palace Winter Garden which was created as counterpoint to the harsh and cold long winters to capture the rare and precious light.

The Winter Garden at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

The history of the Gauguin collection at the Glyptotek winds its way with as much convolution as Gauguin's peripatetic journeys and dramas through its family-based directors and owners, most especially, admirer Helge Jacobsen, the son of the founder Carl who was at odds with his father's more conservative collecting. Many of the examples are from Gauguin's earlier, Impressionist period but curator Line Clausen Pedersen has displayed them so that we may see the progression towards the later, more important work of which there are also examples.

Oddly, this pot pourri of architecture and art and family drama prepares us for the narrative that she presents about Paul Gauguin himself for much like Picasso, Gauguin was a collector, hopscotching around the world, carrying with him his influences and memories no matter where he was, seizing the primitive. (Clausen Pedersen is also the co-curator of the Rousseau exhibition currently at the Getty)

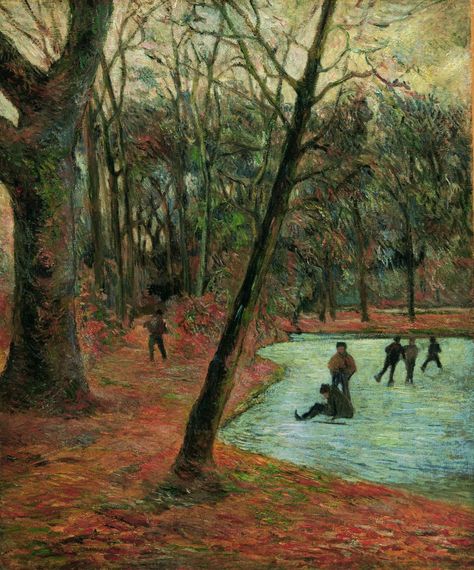

Skaters In Frederiksberg Gardens, 1884, Paul Gauguin

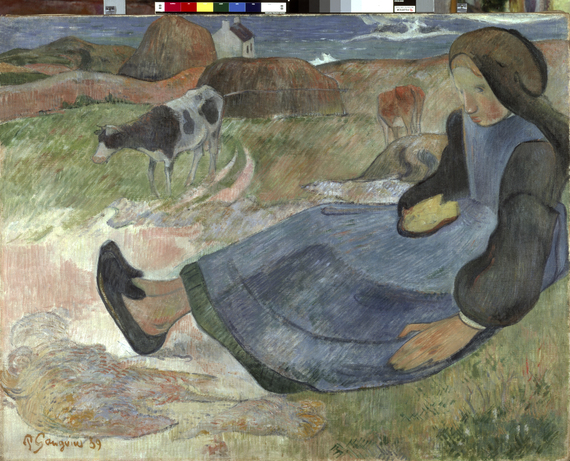

At the outset Gauguin copied his mentor Pissarro and his idol Cezanne. But his gradual transformation from copyist to his own highly original and justly famous hand is amply displayed. Gauguin calculated at the end he had done about 300 canvases and that 100 do not count 'being the work of a beginner". Known however most widely for his high period Tahitian work and only slightly less so for his flat planed colorful curvilinear Breton canvases, Clausen Pedersen makes the case that even in his earlier Impressionist work you can see the inspirations that turned Gauguin on and remained with him, quite literally as he traveled around the world.

"He's trying to make a meal from the refrigerator; cook from what you've got," she says with a wry grin. She makes the point that each painting contributed something to the work we know him for today, "I have an aim and I am always pursuing it, building up material, " he wrote. "There are transformations each year, it is true but they always follow each other in the same direction."

At varying times a sailor, a tarpaulin representative and a stockbroker, Gauguin did not come to painting full time until the age of 35 and thus challenged himself to learn everything at a voracious pace. He cleverly aligned himself with Pissarro and even built up a personal collection of mostly Impressionist works that stood him in good stead when penury reached out and grabbed hold. Often destitute, in poor health but blessed with an ego and passion to be recognized that overcame the vicissitudes of his daily challenges, he made every effort to compete both at the Salon exhibitions and the Independent Impressionist shows with only occasional success.

Mette Gad Gauguin, by Paul Gauguin, 1873

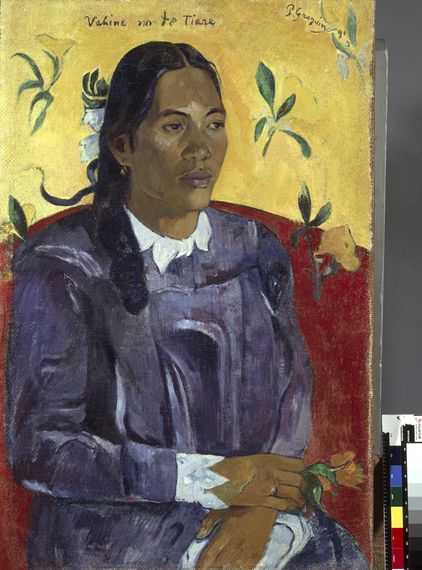

It's the dark, voluptuous, rounded Tahitian women we remember when we think of Gauguin. But it turns out his longest, albeit reluctant, support system--was a pants wearing, large boned, Nordic looking Dane, his wife Mette Gad, whom he had met and married in Paris, who had no choice but to accept her genius husband's free spirit and get on with things. She sold his works to support her family, sometimes sending a portion of the proceeds to him, and was the recipient of scores of letters directing her to do things for him, imploring her to let the children still speak French, bugging her to remember to send him mattresses and blankets and his fur coat.

Neither a muse nor a model, but rather the sometimes plucky independent, sometimes infuriated victim, Gauguin and Mette had 5 children over ten years despite his roving eye. They moved to Copenhagen when the stock market collapsed and Gauguin found himself out of work. After just seven months in the cold, dreary city, remonstrations by her family who had anticipated the wages of a banker, and a gentry largely underwhelmed by his output, he quit Copenhagen in 1884 for Paris, paranoid but unrepentant, with one of the children, a son who was mostly shipped out to stay with friends or at boarding schools and eventually died as a teenager.

Mette and Gauguin thus had a tempestuous, mostly long distance epistolary relationship. They had precious little faith in each other. Yet practically until the very end of Gauguin's storied life, he wrote to her professing love and trying to justify his need for freedom. She wrote sparingly in return but needed his continued output to support the family. Indeed, she acted as agent, promoter and helped seed Denmark with a very large collection of his work.

Breton Girl, 1889 by Paul Gauguin

Gauguin's first exhibit in Copenhagen was short and not so sweet. But he fanned the flame of controversy so that he might burnish his reputation as a revolutionary.

" One day I will tell you....how serious criticisms in my favour were suppressed in the [Danish] newspapers," he wrote her. "Of all the dirty intrigues...the frame makers would lose all their other customers if they made a frame for me... I expect anything from your country and your family," he railed. Mette seems to have largely ignored his rants.

"I know quite well that you do not believe in me unless I am selling pictures," he continued in 1888 as he began to make a reputation. " but this is an opinion that must be concealed from the public. I quite understand that this lousy painting has been your ruin but since the harm is done you should accept the position and try to derive profit therefrom for the future...there is profit and loss in the game," he continued, "and you ought not to share in the joy if you refuse to share in the pain."

Gauguin had been born in Peru of French parentage but returned with his parents to live in France. He became a 16 year old sailor in around the world ventures "You must remember two natures dwell in me, "he wrote Mette, "the Indian and the sensitive man. The sensitive being has disappeared and the Indian now goes straight ahead."

After Paris he went to a growing artists colony in Brittany because it was cheaper, then headed for Panama (to work on an aborted French canal) and Martinique and Arles (to co habit with Van Gogh who greatly admired his work and acted as his agent for a time). "No constipation and regular coitus, with independent work, and a man can pull through," he said from there when things were going well. By 1890 he felt his reputation had grown a little but what he refers to as his "solitary life" still makes him "miserable".

Martinique Woman with Kerchief , by Paul Gauguin, 1887-8

Then he's back to Brittany again after his dramatic bust up with Van Gogh, but not content, returns briefly to Copenhagen to try to convince Mette to accompany him and then finally departs alone for his a two year trip to the South Seas, intending for the Java he had seen at the immensely stimulating Paris International Exposition of 1889 but ending up in Tahiti.

Landscape from Tahiti, Paul Gauguin, ca 1893

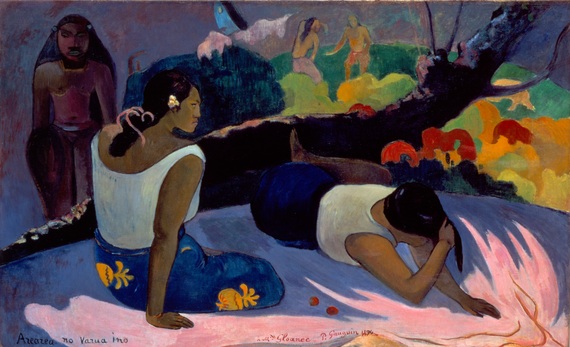

Yet he took with him memories of Europe, of Millet, of Delacroix, of Russian and Christian icons, of Japanese motifs, of things he had seen at the Exposition, not just postcards but actual cult objects that had aroused his artistic juices. Clausen Pedersen has arranged a stack of shelves with these influences. "You become what you eat", says Pedersen, continuing with her metaphors of food and ingestion. "Let's make art as complicated as it is".

Gauguin and Mette saw each other only once more in 1893 very briefly in Copenhagen when he tried to convince her to come with him to the South Seas.

"May the day come...when I can flee to the woods on a South Sea island and live there in ecstasy, in peace and for art, with a new family, far from this European struggle for money," he had written to her, "free at last with no money troubles and able to love to sing and to die." She remained unconvinced but he took with him memories of her--"a precious pearl"--despite their estrangement. " I was delighted to see you in April but could not fail to notice in you the same characteristics which would make our life together so difficult--the same rebellious instincts, strong than ever, the same leaning to flattery rather than to truth."

Reclining Woman with A Fan, Paul Gauguin, c 1889

Despite her silences, and no news of his children, he continued to write her and implore her to stay in touch. Gauguin co habited with many women, vahines, in the South Seas including a 14 year old and should not be excused for his predatory, selfish behavior. But all the while he was either sending work back to her or she was making ends meet by selling off the Impressionists Gauguin had wisely collected. "Sell ..the sketch by Degas...but the sale of the Manet and Miss Cassett (sic)must be stopped....The important thing is to push mine." Mette took on translation and teaching work as Gauguin's contributions became minimal and well known Paris dealers came occasionally to represent him.

Gauguin was immensely frustrated by his domestic woes, but also bitter about his invisibility in the art market. He was exhibited to a mostly indifferent public while self-promoting as a rebellious iconoclast and with his irate letters to critics and in magazines, begin to create the legend he is known for. Despite his South Sea wanderings, he still measured himself by western ideals and success.

Tahitian Woman with a Flower, Paul Gauguin, 1891

Though he often refers to their someday getting back together with Mette when circumstances are right, she seems to have held out little hope that that day would occur after the "vile tempers" on both sides that had caused the break up.

"As to being reunited one day, I don't think about it as I cannot see how it can be done," he agreed. Without funds, I cannot summon the energy to give you the comfortable life you need...you are enjoying the amenities of marriage without being bothered by a husband...love at a distance doesn't cost much...you have left me no illusion about the future so you mustn't be surprised if one day...I find a woman who will be something more to me...."

As years have gone on there seems to some difference of opinion among scholars as to whether she was an indifferent shrew or a much put upon victim. " As for my friends who gossip and who are not yours, let me tell you that all this tittle tattle comes from people who are not French, consequently your friends."

Arearea no varua Ino, by Paul Gauguin, 1894

He returned after two years bringing with him the bursts of color we know him for but which also incorporate the flatness and curves from his stay in Brittany. What's also striking is that paintings we think must have had been painted in Tahiti were often in fact painted elsewhere. Clausen Pedersen says, " He's always depicting wherever he isn't". It's the memories in his hand as well as in his mind, the deep carvings that he saw in Copenhagen, the singular hats of Brittany, that he packs in his suitcase of inspirations. "I tell you that I shall eventually do first class things, I know it and we shall see...mark this well...a wind is blowing at this moment among artists which is all in my favour..." But though an inheritance came his way, he was soon again over extended and longed for the sensuality and inspiration of the tropics. He always felt his art held him to a different standard, and with poverty as a constant companion, he was able to both ignore his family and long for them at the same time.

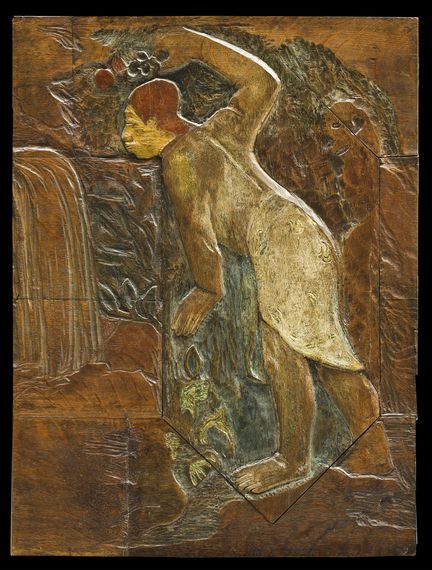

Also striking at the Glyptotek are the collection of wood carvings and pottery which show an even more direct import of native craft into his practice.

Papa moe, by Paul Gauguin 1894

On his return trip to Tahiti and the Marquesas to recapture the genie, he suffered from multiple stresses which inhibited his final output.His beloved daughter Aline died in Copenhagen. That tragedy coupled with his continued bad health and his frustration with the art market drove him back to despair. (Many of his symptoms are said to have had their root in syphilis. He took arsenic, the remedy of the time, which had dire side effects). He wanted to prove himself but his hard living and nomadic existence did not pave the way for an easy retirement and though he was happy with some of the work he never achieved the level of recognition he feels he merited.

"For I am an artist and you are right, you are not mad," he railed at Mette. " I am a great artist and I know it. It is because I am such that I have endured such sufferings. To do what I have done in any other circumstances would make me out as a ruffian. Which I am no doubt for many people. Anyhow what does it matter? ....You tell me that I am wrong to remain far away from the artistic center. No, I am right. I have known for a long time what I am doing and why I do it. My artistic center is in my brain and not elsewhere and I am strong because I am never sidetracked by others, and what is in me... "

Until the end he was defending his work to his critics, his creditors, his debtors

..."the martyr is often necessary to every revolution....the emancipation of painting...of this accursed tissue woven by the schools, the academies and specially the mediocrities...look what may be dared today compared with the timidity of ten years ago...what a strange a mad public it is that exacts from the painter the utmost originality and then only accepts him when he is like the others?"

With his wife however, all correspondence had finally ceased.

Had she sold paintings and not given him any proceeds? Most certainly. But what other resources did she have? He had given her hardly anything from his inheritance. For her part, his "monstrous egoism" finally served to rupture their almost wholly epistolary relationship.

---

The Ny Carlsberg Glyptoteket Museum is in central Copenhagen not far from the Tivoli Gardens and the Gauguin exhibition runs through August 28.

There is one other strong Gauguin collection at the Ordrupgaard Museum just north of Copenhagen that buttresses the odd couple pairing of Gauguin with Denmark.

A new companion exhibition On the Verge of Insanity opens in Amsterdam at the Van Gogh museum on July 15 which explores the time period they lived together.

Paul Gauguin: Letters to his wife and Friends, Edited by Maurice Malingue, 1949 (at your public library) is a marvelous collection which gives primary insight into the artist and his demons.

This is Part 1 of a cultural overview of Copenhagen. Part 2 will appear shortly.