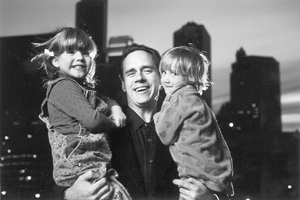

To say New York Times media columnist David Carr has had a troubled past would be an understatement. A former crack addict, he beat cancer to gain custody of the two daughters he had with his junkie girlfriend. His life story seemed to have the perfect Hollywood arc. But no one, not even Carr himself, knew just how interesting that story really was -- that is, until Carr dove back into his past armed with a videocamera and a desire to uncover who he had once been.

His recently published memoir, "The Night Of The Gun," has been praised not only as the amazing story of a junkie who pulled himself out of the depths of addiction, but also as a truthful one that reveals just how muddled and messy that climb was.

Here's our interview with Carr, who answered a list of questions for us by email while on a promotional tour for the book.

Why write this book?

I wrote the book because I thought I would be good at it and that other people would see a value in it beyond my personal travails. I was a hopeless case, and I managed to get off booze and drugs, raise children, obtain gainful employment and resume a role in civil society. There is a nice symmetry to the motivation because the two girls who are at the heart of the story were coming of college age and I needed, like any parent, to fund at least part of their education. (That's part of the reason their mother agreed to sit for a long interview as well.)

Some people try to forget their pasts -- why try revisiting it publicly? (Has it been therapeutic?)

It's been embarrassing and weird in ways I was clueless about - ironic given the fact that I write about the media - but yes, it's been therapeutic in the sense that staring into the wreckage of one's past is a good way to resolve not to go there again. I wasn't really thinking about disclosure when I wrote the book. I just tried to write a good and true story. I think a lot more about disclosure now that I am living with the book, but as Hunter Thompson said, buy the ticket, take the ride.

Who's your audience? Do you think the book will appeal to people who are already familiar with your checkered past, or those who had no idea about it?

I didn't think a lot about audience. I didn't really have a need or a desire to deepen people's understanding of what a jerk I was and I don't think there was a lot of awareness of my past out there to mine in the first place.Beyond that, there is so much misogyny in the front of the book, that I though that women would have trouble with the book, but they have been the most ferocious readers of the book. I think they read it because they care about the children that are at the heart of the book, and only secondarily about the 200 pounds of ugly they are stapled to. And although it has been slower in coming because it is not a standard recovery tract, people with substance issues are now all over the book in a way that makes me happy. All of the best reviews of the book have come from people who understand addiction as personal, cellular level.

What's the night of the gun?

The night of the gun was an incident in which I was so out of box that I recalled a friend of mine had to pull a gun on me to make me go away. As I reported out that incident, I found out that there may have been a gun, and somebody might have pointed it, but it wasn't pointed at me.

Beyond that, I like the sound of it - it's kind of weird and spooky - and probably has commercial value, I think. If I had entitled it, say,"Safe at Home: A guy from New Jersey talks about his lawn, his kids and the weird journey that brought him there," I don't think I would have had much of a shot in the marketplace.

What's too personal? What won't you share?

How can I share about things I won't share? I didn't go into specifics about health matters of other people, I didn't talk about the pharmacological habits of people I didn't talk to, and I didn't spend a lot of time on career matters, but mostly because I thought it would boring and so did others.

What's something that didn't make it into the book?

A bunch of stories about rock band hijinks. I was a hanger-oner in the Mpls music scence and I thought writing about those days would make me seem like a dork and a fanboy. Which I am.

If your memory is so suspect, how can you rely on the memories of others?

I didn't rely on other people's memories. We had conversations about the past, and then I used those conversations for further reporting, triangulation and tried to write about the truth that lay between us.

Could you have written this book without the interviews?

Sure. And it might have been okay, but it would have been a different book. Come to think of it, if I didn't come up with the idea of fact-checking the past, I probably would not have gone there. I have my issues with narcissism and self-involvement, but they probably are not audacious enough to fuel a long conversation with myself about myself.

Was this book made possible by statutes of limitations?

Yes. People spoke freely about the past because the statute had run and many had moved on to other things. But that distance hurt the book too. Because I waited 20 years to investigate many of the signal events, relevant medical and legal records had been thrown out. My file from Eden House, a therapeutic community where I lived for six months, would have been a doozey, but it was long gone.

How do your daughters Meagan and Erin feel about this book?

We are in Minneapolis for readings and they seem happy with the book - give or take an ending that they both find to be a little pat. And it is not presence in their lives like it is for my wife or myself. Sad to say, but if you want to hide something from 20-year-olds and their peers, a book is a pretty good place to stash it.

You seem to gloss over the inner motivations that made you an addict and made you quit--you avoid probing into your psyche. But the story seems almost incomplete without a deeper explanation. Why didn't you go there?

I've had a lot of great reviews, but that is a fairly consistent critique. I once wrote about somebody that they seemed to be self-involved without being self-aware and maybe that attains with me as well.

Part of it has to do with civilians reviewing the book. When you are not a drunk or an addict, it is hard to understand why what Pavlov called 'the blind force of the subcortex' will compel you to do dumb stuff. I didn't set out to be a lunatic, I just liked getting high more than normal people.

Has your book--with its meticulous reconstruction of your past based on records and interviews--set a new standard for memoirs?

Naw, I don't think so. In the past 2000 years, many of the great works of literature have come from people who have stared into their past with nothing more than a quill and a blank sheet of paper and created magnificent, enduring works. But I'm not that guy. I'm a hack newspaperman who finds both value and real literary traction in inquiry. I did not report this book as a corrective. I did it that way because my day job has taught me that my stories get better when I talk to other people.

What's between you and a relapse? What steps do you take to prevent it?

I have a very basic program of recovery that involves meetings and a way of living. Its never failed me unless I have failed it. Two things are working in my favor right now. One is that the book taught me stuff I had forgotten, that there are more things at risk if I use that just my well-being. And the last bit of personal research that I did - I took a whack at being a suburban drunk and succeeded wildly - is something that is with me in a very present tense way. (And apart from that, I'd like not to be the author of a recovery memoir who is heading back to his hotel room to have a long conversation with a bottle of whiskey.)

When you were researching this book, did you feel an urge to relive your wilder days?

Every day that I worked on this book took me farther away from a drink or a drug. I did not plan for that and had my concerns about the dark places it would put me in. It went the other way. Lucky break.

Have you replaced your old addictions with new less dangerous ones?

I am on my fourth cigarette since I started typing, so addiction is still with me and still plenty dangerous. It's three in the morning and I am sipping coffee and typing as well, so I doubt that anybody would point to me as a paragon of a healthy lifestyle.

What movie do you think best captures a junkie's life? Have you seen "Requiem For a Dream"? "Drugstore Cowboy"? What did you think?

"Requiem for a Dream" is one of the best movies of the last two decades, but I don't really connect to it as an addict. The drug of choice is heroin and it has a prismatic visual style that does not comport with the boredom of prosaic addiction. On a personal level, I connect with "The Wire" and the character Bubbles, even though he was a heroin guy. David Simon is one of the few contemporary American writers who steps to addiction and recovery absent tropes with all of the complications life entails. I never lived that street life, but there is something fascinating and resonant about the negotiations amongst and between addicts, the law, and the culture at large. And anybody who really wants to know what cocaine is about should skip the movies and read "Clockers." Nothing else touches it.