"He who paddles two canoes, sinks."

- Bemba proverb

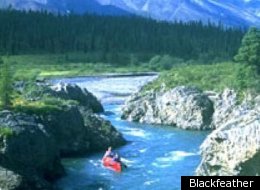

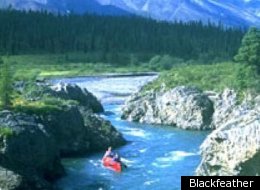

We were on a river so remote it doesn't exist on most maps, the Blackfeather, a tributary of the Mountain River, deep in the Mackenzie Mountains of Canada's Northwest Territories about 100 miles south of the Arctic Circle. These are wilderness waterways in the truest sense: The courses have no impoundments, no diversion projects, no bridges, no roads, no homes, no people, no pollution.

The Mountain Dene people once hunted and trapped here, but they long ago moved to villages on the Mackenzie, and now the only remnant is a void. These rivers flow, as they have since time immemorial, in balance with themselves. The Blackfeather and Mountain, and every rill that feeds then, are in unmodified natural states. If they belong to anyone, they belong to the wildlife, superbly adapted to this inimical region: moose, wolf, wolverine, Dall sheep, mountain caribou, beaver and grizzly bear. My canoe mate was my friend Erik, the former C.E.O. of Expedia. The other in our party was our part-time-male-model guide Bart, who was making his first descent. Our plan was to catch up with Erik's dad, John, and our master guide, Tim, a veteran of many northern river trips, who had launched the day before us.

The Mountain Dene people once hunted and trapped here, but they long ago moved to villages on the Mackenzie, and now the only remnant is a void. These rivers flow, as they have since time immemorial, in balance with themselves. The Blackfeather and Mountain, and every rill that feeds then, are in unmodified natural states. If they belong to anyone, they belong to the wildlife, superbly adapted to this inimical region: moose, wolf, wolverine, Dall sheep, mountain caribou, beaver and grizzly bear. My canoe mate was my friend Erik, the former C.E.O. of Expedia. The other in our party was our part-time-male-model guide Bart, who was making his first descent. Our plan was to catch up with Erik's dad, John, and our master guide, Tim, a veteran of many northern river trips, who had launched the day before us.

To get to our river we first flew commercially to the oil pipeline community of Norman Wells on the Mackenzie River. From there we boarded a Swiss-made Pilatus PC-6 Porter, a STOL (short take-off and landing) floatplane, often called the "Jeep of the air."

The high-winged, angular black and yellow Porter took us farther north and east into an intermontane basin in the Mackenzie Range, over a spot of water that looked like a human eye brooding. It seemed to mirror the soul of the landscape. We splashed down on Willowhandle Lake, at about 4,000 feet. The air is usually the first sign that you are someplace different, but here, as we stepped off the pontoons, it was the light--soft, diffuse, and intense all at once.

The high-winged, angular black and yellow Porter took us farther north and east into an intermontane basin in the Mackenzie Range, over a spot of water that looked like a human eye brooding. It seemed to mirror the soul of the landscape. We splashed down on Willowhandle Lake, at about 4,000 feet. The air is usually the first sign that you are someplace different, but here, as we stepped off the pontoons, it was the light--soft, diffuse, and intense all at once.

The air, too, made its point. It was autumn cold, and I looked to the south for a piece of last warmth before the sun made its last horseshoe pass around the margins of the sky.

The air, too, made its point. It was autumn cold, and I looked to the south for a piece of last warmth before the sun made its last horseshoe pass around the margins of the sky.

Because of schedule conflicts, the rest of the party had launched the previous day. Erik and I climbed into one canoe, Bart in the other, and together we took off sliding across the glasslike lake, all silent except for the periodic calls of loons echoing across the canyon, and the swish of water as it broke across the hull. At the far end we hoisted the canoes and kits on our heads and backs and began a kilometer portage along a faint track littered with fresh Grizzly tracks. We made camp at a creek called Push-Me-Pull-You.

As we turned our canoe over to become a makeshift dinner table, I saw the bottom scored with a matrix of scratches and dents, the scars from a season in tough waters.

As we turned our canoe over to become a makeshift dinner table, I saw the bottom scored with a matrix of scratches and dents, the scars from a season in tough waters.

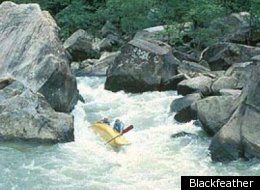

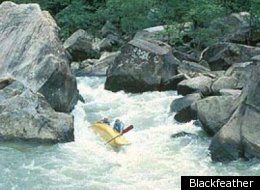

The next day we loaded the boats and proceeded to push and pull them down a water passage not much bigger than a garden hose. It was back-breaking work in stinging cold water, which lasted all morning. Eventually the trickle conflued with the Blackfeather, and there was a last the thrill of a live vessel beneath us riding high over brawling water--until the boat began to crankle as though drunk, and our misadventures began.

Click the audio button to find out what happened next...

---

Richard Bangs' authored The Lost River about his first descents of Ethiopian rivers, including the Omo and Blue Nile and co-authored Mystery of the Nile in 2005.

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

It's Another Trump-Biden Showdown — And We Need Your Help

The Future Of Democracy Is At Stake

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

Your Loyalty Means The World To Us

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

The 2024 election is heating up, and women's rights, health care, voting rights, and the very future of democracy are all at stake. Donald Trump will face Joe Biden in the most consequential vote of our time. And HuffPost will be there, covering every twist and turn. America's future hangs in the balance. Would you consider contributing to support our journalism and keep it free for all during this critical season?

HuffPost believes news should be accessible to everyone, regardless of their ability to pay for it. We rely on readers like you to help fund our work. Any contribution you can make — even as little as $2 — goes directly toward supporting the impactful journalism that we will continue to produce this year. Thank you for being part of our story.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

It's official: Donald Trump will face Joe Biden this fall in the presidential election. As we face the most consequential presidential election of our time, HuffPost is committed to bringing you up-to-date, accurate news about the 2024 race. While other outlets have retreated behind paywalls, you can trust our news will stay free.

But we can't do it without your help. Reader funding is one of the key ways we support our newsroom. Would you consider making a donation to help fund our news during this critical time? Your contributions are vital to supporting a free press.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our journalism free and accessible to all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. Would you consider becoming a regular HuffPost contributor?

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. If circumstances have changed since you last contributed, we hope you'll consider contributing to HuffPost once more.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

The Mountain Dene people once hunted and trapped here, but they long ago moved to villages on the Mackenzie, and now the only remnant is a void. These rivers flow, as they have since time immemorial, in balance with themselves. The Blackfeather and Mountain, and every rill that feeds then, are in unmodified natural states. If they belong to anyone, they belong to the wildlife, superbly adapted to this inimical region: moose, wolf, wolverine, Dall sheep, mountain caribou, beaver and grizzly bear. My canoe mate was my friend Erik, the former C.E.O. of Expedia. The other in our party was our part-time-male-model guide Bart, who was making his first descent. Our plan was to catch up with Erik's dad, John, and our master guide, Tim, a veteran of many northern river trips, who had launched the day before us.

The Mountain Dene people once hunted and trapped here, but they long ago moved to villages on the Mackenzie, and now the only remnant is a void. These rivers flow, as they have since time immemorial, in balance with themselves. The Blackfeather and Mountain, and every rill that feeds then, are in unmodified natural states. If they belong to anyone, they belong to the wildlife, superbly adapted to this inimical region: moose, wolf, wolverine, Dall sheep, mountain caribou, beaver and grizzly bear. My canoe mate was my friend Erik, the former C.E.O. of Expedia. The other in our party was our part-time-male-model guide Bart, who was making his first descent. Our plan was to catch up with Erik's dad, John, and our master guide, Tim, a veteran of many northern river trips, who had launched the day before us. The high-winged, angular black and yellow Porter took us farther north and east into an intermontane basin in the Mackenzie Range, over a spot of water that looked like a human eye brooding. It seemed to mirror the soul of the landscape. We splashed down on Willowhandle Lake, at about 4,000 feet. The air is usually the first sign that you are someplace different, but here, as we stepped off the pontoons, it was the light--soft, diffuse, and intense all at once.

The high-winged, angular black and yellow Porter took us farther north and east into an intermontane basin in the Mackenzie Range, over a spot of water that looked like a human eye brooding. It seemed to mirror the soul of the landscape. We splashed down on Willowhandle Lake, at about 4,000 feet. The air is usually the first sign that you are someplace different, but here, as we stepped off the pontoons, it was the light--soft, diffuse, and intense all at once.  The air, too, made its point. It was autumn cold, and I looked to the south for a piece of last warmth before the sun made its last horseshoe pass around the margins of the sky.

The air, too, made its point. It was autumn cold, and I looked to the south for a piece of last warmth before the sun made its last horseshoe pass around the margins of the sky.  As we turned our canoe over to become a makeshift dinner table, I saw the bottom scored with a matrix of scratches and dents, the scars from a season in tough waters.

As we turned our canoe over to become a makeshift dinner table, I saw the bottom scored with a matrix of scratches and dents, the scars from a season in tough waters.