The Crucible is a play about a horrible moment in American history, born of another horrible moment, and therefore literally tailor-made for such times. Arthur Miller wrote his play of the Salem witch trials of 1692-1693 in 1953, a decade wracked by the Cold War and hearings called by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and, on the Senate side, by Joseph McCarthy. Miller, who had won a Pulitzer Prize in 1949 for Death of A Salesman, would answer HUAC questions about himself -- but not about others -- in 1956. Out of this climate of surveillance and suspicion he made dark art that has a particular power on Broadway at the start of 2016.

Director Ivo Van Hove and his design team have focused, as in part one must, though they've done it a bit too much, on the fact that this is a tale of witches and the supernatural. The production is quite cinematic, with bright lights and weird sounds and, at one point, a possessed girl in her nightgown suspended in midair. Philip Glass has supplied a signature pulsing, relentless ripple of a soundtrack that, for me, served less to heighten any emotion than muffle it: you can't hear Miller's words above everything else for too much of the time. Ssshhhhhh. Listen to the language of the play. It will scare you to pieces, all on its own.

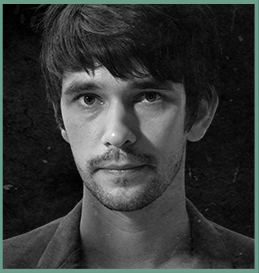

Ben Whishaw is John Proctor

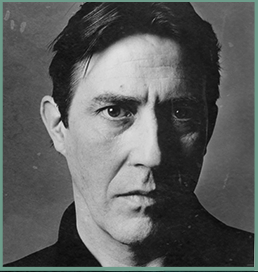

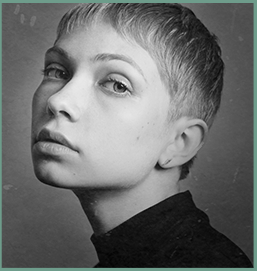

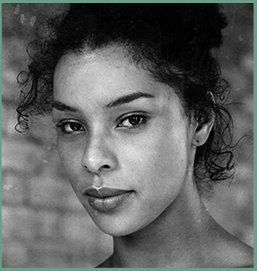

The individual performances, overall, amaze. Ben Whishaw is breathtaking as John Proctor, the farmer who keeps the Sunday by tending to the fields he loves instead of worshiping in the church of a weak, yet strident, minister (the perfectly awful, and therefore perfect, Jason Butler Harner). The strongest scenes in the play are the quietest ones, both between Proctor and his wife Elizabeth. Sophie Okonedo, as Elizabeth, is beautiful and strong and vital; her coda to the action of the play made me weep. Ciarán Hinds and Jim Norton were recently on stage together as Claudius and Polonius in Hamlet, at the Barbican in London. Reunited here as Deputy Governor Danforth and Giles Corey, they easily dominate every scene they're in. Hinds is a cold, inexorable hanging judge whose rationality flies in the face of the witchcraft he wants to find under every suit of sober Sunday best. Norton gets some of Miller's best lines, as, for example, he corrects Reverend Hale (Bill Camp, by turns passionate, frustrated and heroic), "I never said my wife were a witch, Mr. Hale; I only said she were reading books." When offstage his final words are reported -- "more weight" -- they chill you to the heart. Saoirse Ronan, making her Broadway debut as Abigail Williams, is piercing and entirely unsympathetic, and this fits the role. Instead of feeling sorry for a homeless orphan, you shrink from the stratty-haired, staring Mean Girl. She leads the troop of girls (dressed in school uniforms, like the witches at Hogwarts) through their litanies and wild dances with a potent proficiency. However, the star turn among the possessed girls -- who damns her friends for lying and urges them to stop, but visibly changes her mind to save her own skin -- is from Tavi Gevinson as Mary Warren. When Hinds, in that caress of a voice, refers repeatedly to her as "child, my child" and the other men chime in with it, too, it is terrifying: the man who brings law, order and death to the community, trying and failing to infantilize grown women desperate for something to do, someone to be.

The Salem witch trials really happened. The girls in Salem town were younger than Miller's characters: Betty Parris, the minister's daughter, was nine, and her cousin Abigail Williams was eleven. However, the names he uses, and the fates of real individuals, comport with history. Mary Warren was the servant of John and Elizabeth Proctor. People named Good and Deliverance, Nurse and Hale, lived and died in Salem, some accused of witchcraft by friends and neighbors -- and some of whose friends and neighbors went on to claim or buy their land. Greed for property, lust, boredom: these are all among the reasons, or "reasons," Miller incorporates in the action of his play. In her stunning book In The Devil's Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692, historian Mary Beth Norton reminds us that the people of Salem had survived Indian wars and were still reeling from their status as frontier pioneers. An ergot blight on food crops, chiefly rye, in 1691 could have poisoned those who ate rye bread, leading to hallucinations, convulsions, and other symptoms the girls manifested.

Tavi Gevinson is Mary Warren

That The Crucible has its roots in double reality -- past facts, and whatever resonances ensue in each time when it is produced -- will keep it a frightful play. The current Crucible on Broadway is performed by almost exclusively English and Irish actors; their accents remind you that Salem, 1693, was in New England, in the newly-chartered Province of Massachusetts Bay. It could be a comfort to try to pretend that this was not yet America, these people so eager to undo each other, to blame and accuse, to love and grieve. However, it won't work. The historical fiction of the play serves only to remind you, as William Faulkner famously put it, that the past is never dead. It walks with us, full of hysteria and paranoia, prejudice and fear, and all the bad things we keep wishing humanity could mend or ignore or outgrow, right out of the little Walter Kerr Theater and into the after-theater crowds on 48th Street. Go see The Crucible. It won't make you feel good, but it will make you feel. Miller's words ring alarm in your ears and put ice in your bones.

Sophie Okonedo is Elizabeth Proctor

all portraits via Crucible on Broadway